he 2015-2016 Broadway season had the world thinking that theater had done what Hollywood couldn’t — it was, so it seemed, truly inclusive. The unprecedented success of Hamilton underlined the marketability of color-conscious casting: Lin-Manuel Miranda deliberately wrote his musical about America’s founding fathers to be performed by actors of color (with some notable exceptions). And while that’s not the sole cause of the show’s record-breaking ticket and album sales, it certainly figured into the praise that’s been heaped onto it.

It wasn’t just the staggering rise of Hamilton that had theater writers and fans alike celebrating a new, less white era in musical theater. Other crowd- and critic-pleasing hits like The Color Purple (with an all black cast) and On Your Feet (with a largely Latinx cast), and groundbreaking shows like the Asian-American-led Allegiance and Deaf West’s Spring Awakening highlighted the importance of not just white people without disabilities leading shows on New York’s most vaunted stages. When the Tony nominations were announced, the #TonysSoDiverse hashtag quickly emerged, a progressive antidote to the racial homogeneity of the Academy Awards and the accompanying #OscarsSoWhite campaign against them. And, for the first time in Tony history, all four musical acting awards in 2016 went to black performers. “This Broadway Season, Diversity Is Front and Center” read a New York Times headline from September.

But for Asian-American actors, there is a persistent fear of being left out of the conversation entirely, since “diversity” has often been conflated with black representation only. As Hamilton star Leslie Odom Jr. put it, “In America, things get boiled down into a black and white issue, but I want to see stories about Asian people, I want to see stories about trans people — diversity is not just a black and white issue. … We’ve still got some work to do when you talk about real diversity.”

After all, the 2016-2017 season on the Great White Way already looks distinctly whiter than the last. Even with The Color Purple and On Your Feet still going strong, the 2015-2016 season may have been, as Miranda himself even called it, “a fluke.” Despite that not-so-optimistic assessment of what had been hailed a groundbreaking year in theater, Miranda did conclude in the same June 2016 interview, “The exciting lesson that I hope people are taking away from Hamilton is that you don’t need a white guy at the center of things to make it relatable.”

But Broadway clearly isn’t convinced that an Asian-American guy (or woman) would have the same effect.

“Diversity is not just black and white.”

Ask Jon Viktor Corpuz, who was told by agents that he was “very specific” and would only be able to book certain roles. Ask Erin Quill, who has battled with internet commenters who don’t understand why Christmas Eve — the Japanese character she played in Avenue Q — shouldn’t be played by a white actor. Ask Telly Leung, who was told point blank that Asian stories don’t sell tickets. A dozen Asian-American theater professionals interviewed by BuzzFeed News for this piece shared similar stories: They had all been passed over for roles that were deemed “white” or were asked to lean into archaic stereotypes for “Asian parts.” (It’s worth noting that this piece focuses on East Asian-American actors; the experiences of South Asian-American actors is a different story entirely, equally worth telling.)

As it stands, there are only three Asian-American leads currently on Broadway: Two are in Aladdin — Adam Jacobs as the titular character and Courtney Reed as Jasmine — and the third is Ali Ewoldt, The Phantom of the Opera’s first ever Asian-American Christine on Broadway. There are only a handful of additional Asian-American actors in supporting roles in shows like Wicked, Waitress, School of Rock, and Cats, and a few more in ensembles. Even Hamilton’s original Broadway cast only had one Asian-American actor in a principal role: Phillipa Soo, who has since left. At a time in which Broadway is being celebrated for its unprecedented diversity, the discrepancy is staggering.

“There are holes missing when it comes to diversity,” said Ruthie Ann Miles, who won a Tony Award in 2015 for her role in the King and I revival. “Diversity is not just black and white. … It’s a whole. There are such massive groups of people that are just completely missing from the equation.”

mong its merits, the much lauded 2015 King and I revival offered employment for a sizable group of Asian-American actors. When the show closed in June and the actors took their final bows, they found themselves out of a job. The next Broadway show to offer as many roles for Asian-American performers will likely be the Miss Saigon revival, which opens in March.

There’s a reason why so many actors of Asian descent have found themselves in the constant orbit of The King and I and Miss Saigon, and why producers continue to gravitate toward these historically problematic productions. In an industry where change is often a perilous uphill climb, it’s easy to fall back on what has worked in the past — even if it’s not working well enough. The King and I and Miss Saigon have been criticized for their white savior narratives and their reliance on stereotypes, like the so-called barbarism of the Siamese people in the former, and a reductive characterization of the Vietnamese in the latter. They’ve also previously had to be called out for their use of yellowface casting.

While recent revivals have done admirable work in undoing past mistakes, they are still only two shows and the space between them can be a dead zone for Asian-American actors, who have long been among the least represented ethnic groups on Broadway. That hasn’t changed much in 25 years.

When Welsh actor Jonathan Pryce won the 1991 Tony Award for Best Leading Actor, he very pointedly thanked his fellow “multi-racial” cast members of Miss Saigon. It was an odd remark; this was a white actor playing a half-Vietnamese, half-French character, the Engineer, and he had originally worn caked-on bronzer and eye prostheses à la Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

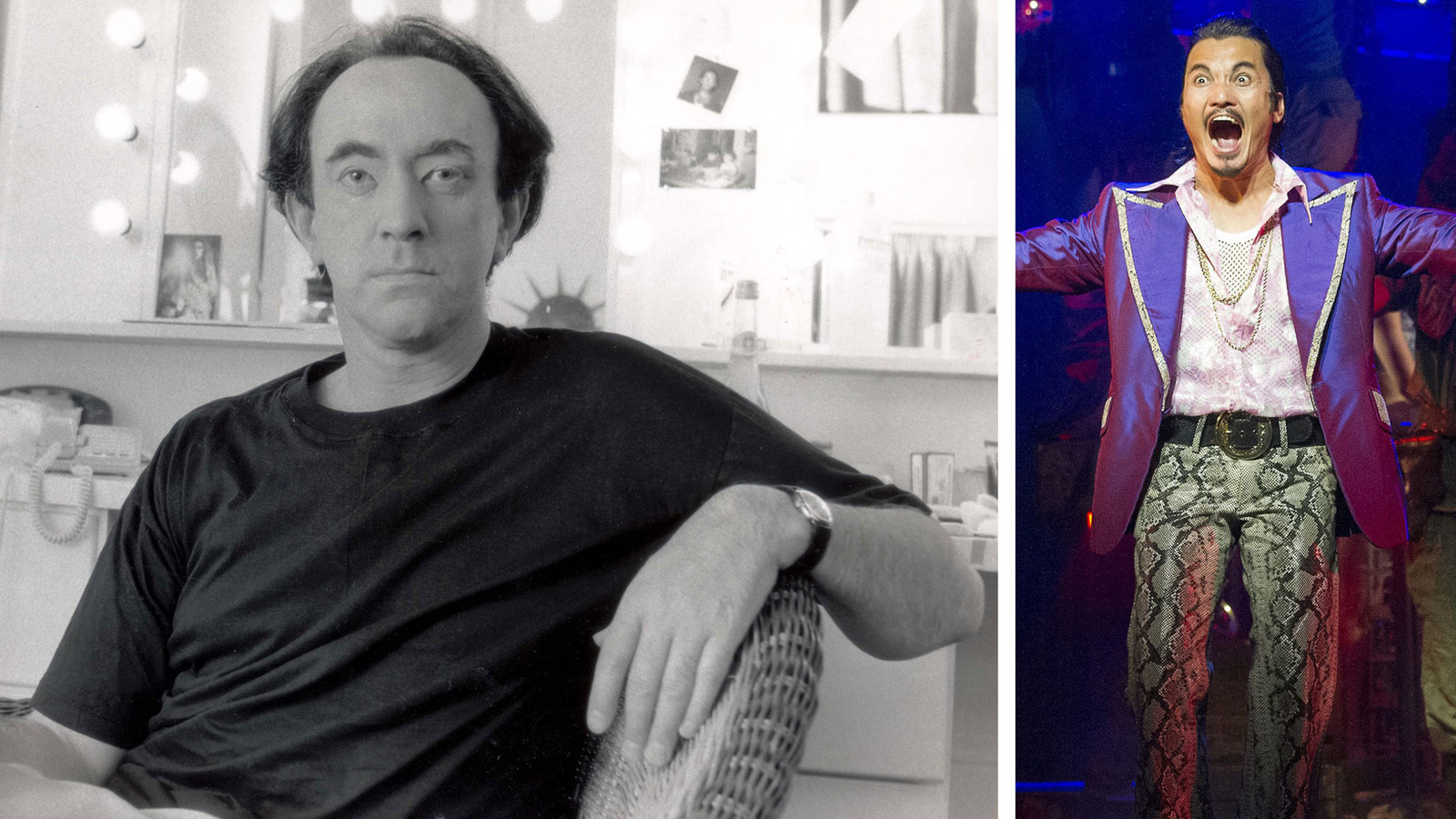

Left: Actor Jonathan Pryce in yellowface makeup for Miss Saigon. Right: Jon Jon Briones as the Engineer in the West End revival. Rex Images / Matthew Murphy / Miss Saigon

n the year leading up to Pryce taking the podium, Miss Saigon was embroiled in a heated battle over its racial insensitivity (another white actor, Keith Burns, co-starred as Thuy, an officer in the North Vietnamese army). David Henry Hwang, the Pulitzer Prize finalist and playwright behind M. Butterfly, was one of the first to draw attention to the issue. In August 1990, amid outrage within the Asian-American community, Actors’ Equity took up the cause after being asked to approve the casting, which is standard practice when an actor who is not a US citizen is cast in a Broadway production.

It wasn’t just the yellowface that Equity objected to, but also that Pryce’s casting thwarted the opportunity for an Asian-American actor to take on a high-profile role. “The casting choice is especially disturbing when the casting of an Asian actor, in this role, would be an important and significant opportunity to break the usual pattern in casting Asians in minor roles,” union representatives wrote in their letter of protest.

At the time, the musical’s casting director Vincent Liff argued that Pryce had to play the Engineer because there simply weren’t any Asian-American “stars.” “The Entertainment industry in the United States … have not provided us (at present) a new generation of middle-aged star performers of Asian background upon which we can draw,” he wrote in a letter to Equity. “It is not that the reservoir is empty at the moment, it’s that there is no reservoir. We have no Asian Theatre ‘Stars.’”

Rather than push back on the ruling, Miss Saigon producer Cameron Mackintosh threatened to cancel the Broadway production entirely.

A counter-uproar ensued, during which time Frank Rich at the New York Times lamented, “By refusing to permit a white actor to play a Eurasian role, Equity makes a mockery of the hard-won principles of nontraditional casting and practices a hypocritical reverse racism.” Equity relented. Miss Saigon proceeded as planned, with an April 1991 opening, and Pryce won a Tony in June. (A representative for Pryce did not respond to requests for comment.)

Mackintosh has since ensured that the Engineer will only be played by actors of Asian descent, including for the 2017 Miss Saigon revival. Filipino actor Jon Jon Briones will play the role, as he did on the West End.

“One could argue that the battle was lost but the war was won,” Hwang told BuzzFeed News in a phone interview. “As a result of the Saigon controversy and the amount of publicity it got, for many years the yellowface casting question seemed to be settled in that producers basically felt that if they cast a white actor in an Asian role, there would be enough of an outcry that it just wasn’t worth the trouble.”

“When you look at the pool of Asian talent, it’s exponentially more bountiful. Unfortunately, the opportunities are not.”

While Mackintosh was unavailable to comment for this story, his representative told BuzzFeed News in an email that, “He has never regretted casting Jonathan Pryce in the role of the Engineer. His brilliant Tony Award-winning performance helped make the show the international success that it’s been for more than 25 years, leading to the employment of hundreds of Asian actors throughout the world.”

The Miss Saigon controversy framed the modern discussion of racial diversity and Asian-American representation on Broadway. But Liff’s original argument that there were no Asian-American actors who could fulfill that critical role would not hold water today.

“When you look at the pool of Asian talent, it’s exponentially more bountiful,” said actor Telly Leung, who starred in the 2015 musical Allegiance, the George Takei-led show that was the only one on Broadway last season to tell a distinctly Asian-American story. “Unfortunately the opportunities are not as exponentially more bountiful.”

According to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC), Asian-American actors made up only 4% of performers on Broadway and in New York City non-profit theaters from 2006 to 2015. The report does not incorporate the 2015-2016 season, which would have seen a significant lift with Allegiance, a musical inspired by Takei’s memories of life in a Japanese-American internment camp during World War II. It’s firmly rooted its Asian-American characters in the US — not Siam or Vietnam — during a shameful saga of American history.

That Allegiance stands out amid its contemporaries speaks to the ongoing struggle of underrepresentation of Asian-American actors and stories on Broadway.

The King and I has long been one of the only musicals with multiple roles for Asian-American actors. First performed in 1951 and revived on Broadway four times since, the Rodgers and Hammerstein show is about a white Englishwoman Anna who brings Western education and European values to the “barbaric” King of Siam. The most recent production, directed by Bartlett Sher, honored the original musical while addressing the archaic elements that have opened the show up to criticism in the past: The actors worked to master an authentic dialect, and Sher made sure to avoid the perception that in the clash between Anna’s Western values and Siam’s Eastern values, the West was always more “civilized.”

But the production also stood out for its casting — this King and I was the first on Broadway to cast only Asian-American actors in Asian roles. (Not to mention the fact that there was an Asian-American understudy for Anna. In February, Ann Sanders became the first Asian-American actor to play the role when Kelli O’Hara took a vacation.)

Over the past 65 years, various productions of the show have repeatedly cast white actors as Thai characters. And the actor most famous for playing the King is Yul Brynner, who was white, despite his spurious claims that he was of Mongol origin.

Jon Viktor Corpuz, who played Prince Chulalongkorn in the recent revival, described white King and I audience members proudly telling him about having played Asian characters in their amateur productions of the musical. At first, he would smile and nod, but by the end of the show’s run, he had started calling them out. “That would never be tolerated if it was blackface,” he said. “For some reason, it’s OK for people to do that, put on bronzer and put on eyeliner and call themselves Asian.”

“Under any circumstances blackface is not OK. But with yellowface, it’s still up for debate.”

Corpuz’s King and I co-star, Daniel Dae Kim, shared a similar sentiment. “Under any circumstances blackface is not OK,” he said. “But with yellowface, it’s still up for debate. It’s still an open question, which is very contradictory.”

The King and I is far from the only frequent offender here: Almost every year, news emerges of another production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado done in yellowface. In 2015, the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players canceled their production following accusations of racism. But even now, Long Island’s Gilbert & Sullivan Light Opera Company is performing The Mikado with white actors.

It’s up to casting directors, producers, and other members of the creative team to determine who is offered which part — but actors decide which parts to go out for and which to ultimately take. Many of the actors interviewed for this piece said that while the behind-the-scenes team shares in the blame for yellowface casting, they also hold white actors accountable for choosing to take on Asian roles.

“Maybe we need another Miss Saigon incident,” Hwang cheekily offered.

Fred Billington and George Thorne in an 1885 production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado. Bettmann Archive

rin Quill was in the original cast of the outrageous puppet musical comedy Avenue Q where she was the understudy for Christmas Eve, a Japanese therapist with a heavy accent written into the character. Her showstopper ballad “The More You Ruv Someone” plays that up, and while it’s deliberately subversive and borderline offensive for any actor to perform, it becomes truly cringe-worthy when sung by a white person, as it has been in regional and high school productions. Nevertheless, plenty of people have defended the casting of white actors as Christmas Eve.

In March, theater writer and advocate Howard Sherman wrote about why that practice is deplorable, but some readers didn’t get it. On Sherman’s Facebook page, a white man sounded off in the comments; his daughter’s high school was producing Avenue Q with a white Christmas Eve, and he felt that she shouldn’t be deprived of the experience just because they hadn’t found an Asian-American student to cast.

The notion infuriated Quill. “When you tell a white actor it’s OK to erase the minority experience, you’re telling them that the minority experience is not worthy of being considered, that the minority experience is of less importance than their own personal satisfaction,” she said. “They’re making these choices out of convenience, out of an overgrown sense of confidence that they can pull off these roles. I think they have to be held accountable.”

Quill’s concern also stems from the fact that, based on AAPAC’s data, the paltry percentage of Asian-American performers on Broadway has wavered between 0 and 4% year-to-year between 2006 and 2015 (there was a boost to 11% in the 2014-2015 season, thanks largely to the King and I revival).

Ali Ewoldt, who was in the ensemble of The King and I before she began as Christine in The Phantom of the Opera, knows that she’s a rare exception on Broadway.

“The percentage of Asian-American actors that are playing lead roles on Broadway, it’s a very small percentage in the greater scheme of things,” she told BuzzFeed News. AAPAC doesn’t even measure the number of Asian-American performers in leading parts.

“I never thought that I would have a leading male role in a Broadway show,” Leung said. He’s worked consistently on Broadway and off since he made his debut in the 2002 revival of Flower Drum Song, but Allegiance was his first time as a Broadway lead. “I had kind of resigned myself to say, ‘Well, why am I doing this? Am I doing this to be the star of a Broadway show? No, I’m doing this because I love to do it, and I love to tell stories this way.’

ven in the 25 years since the Miss Saigon controversy, there is still a pervasive, misguided notion that there aren’t any Asian stars, and that stars are necessary to make shows profitable. Theater stars are of a different class than movie stars — they are household names among a much more select few. They’re also more easily made: Cynthia Erivo wasn’t well known in the US until her Tony-winning performance in The Color Purple, and her talent continued to bring in audiences after mainstream celebrity Jennifer Hudson departed the production. And Lea Salonga, now perhaps the most famous Asian actor working in theater, was a relative unknown until she starred in Miss Saigon.

In short, fame might sell tickets, but it’s far from a show’s only draw. Yes, Hamilton may be the kind of smash hit that only comes around once in a lifetime, but on paper, there was little about the show that screamed “success.”

“It’s a brilliant piece of theater that’s groundbreaking and everything people say it is, but it also proves that they were able to sell a show with no household names or television or movie stars, and cast it the way they have, with the intent to show the story through that lens,” said actor and writer Christine Toy Johnson, who is the equal employment opportunity chair for Actors’ Equity and a co-founder for AAPAC. “The work is the work, and people want to see it.”

It’s not possible to predict the next Hamilton, if such a thing even exists, but producers will no doubt try. There’s likely to be a trickle-down effect — of copycat shows, yes, but more importantly, of shows that capitalize on what has made Hamilton such a unique and vital presence on Broadway.

“My hope is that two things happen — that one, there’s more theater created that is color conscious in a Hamilton sort of way,” Leung said. “And that there’s a lot more ‘why not’ being asked.”

But, as Johnson said of post-Hamilton Broadway, “You can’t expect complete and total revolution right away, unfortunately.”

Leslie Odom Jr., Phillipa Soo, and Ariana DeBose with Lin-Manuel Miranda during their final performance curtain call of Hamilton on July 9, 2016, in New York City. Walter Mcbride / WireImage

onventional stereotypes about Asian people have long kept Asian-American actors from getting cast as leads. In film and television, too, women have been repeatedly written as meek and submissive (the China Doll/Lotus Flower), or mysterious and hypersexual (the Dragon Lady): In Miss Saigon, this plays out in the contrast between virginal Kim and the seductive Gigi. Men, meanwhile, are painted as sexless, which removes male Asian-American actors from the running as romantic leads since producers and casting directors doubt their ability to attract an audience or create palpable sexual tension on stage.

“Our men are usually not desired, not by anyone — they’re not seen as sexual,” Quill said, citing the character of Thuy in Miss Saigon as an example. While he’s an imposing figure, he’s not presented as a viable romantic option for Kim. “Asian-Americans are vastly underrepresented in terms of sexual appeal, unless the woman is slightly submissive or a sexual object.”

Corpuz said growing up as a Filipino-American, romantic leads on stage and screen never looked like him, which made him, at one point, wish he’d been born white. “I’m still in the process of unlearning all these things about what it means to be beautiful,” he said. “This industry is run by people with certain preferences and they have certain beauty standards. And those are the people that are gonna end up on the TV screen or in the media.”

It’s not only about how Asian characters should look, but also how they should act. Asian-American actors are frequently encouraged to play up their “Asianness,” whether in a script or by directors demanding that objectively nonsensical task. When actors are told to exaggerate aspects of their ethnic identity, the expected behaviors are grounded more in stereotypes than in their personal realities. They’re told to act submissive, to mispronounce English words, or to otherwise portray a cartoonish conception of what it means to be Asian. Some actors turn down such roles, but others can’t afford to pass on a paying job, regardless of how demeaning it might be.

Miles described a recent moment where she had to walk away from an audition. “[The project] literally called for any old accent, and I looked at the script and I knew exactly who this person was, and it was unacceptable to me to go into it with a good conscience and do that,” she said. “[These roles are] still being written, and it’s still being expected, and I’m not gonna play that game, so no thank you.”

“We’re never the main player.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum are actors who are ethnically ambiguous, like Aladdin’s Courtney Reed and Phantom’s Ewoldt, both of whom have been told they’re “not Asian enough” for certain roles.

“I’m very in that middle ground, which makes it even more complicated,” said Reed, who is half-Vietnamese. “There’s always gonna be somebody that looks more ethnic or more white than me.”

The lack of Asian-American actors cast as leads limits an audience’s exposure to actors of varying ethnic backgrounds. White people leading a story with Asian-Americans playing cliché supporting roles perpetuates the same regressive stereotypes that keep these actors sidelined.

“Oh, we need a nerd here. We need the hot girl here. A lot of times our casting is used as kind of a punchline, or an anecdote to a story. We’re never the main player,” Quill said. “[Producers] don’t have a view of Asian-Americans in America and their ability to tell stories. They look at us like we are add-ons.”

Johnson said that the failure to cast Asian-American actors in lead roles is part of a self-perpetuating cycle. “If people aren’t given the opportunity to play these roles that will be of high exposure or eligible for the big awards,” she explained, “then it’s a vicious circle because they’re not given the chance to even do them, then they don’t get to be in the position of being quote-unquote ‘sellable.’”

ost actors are less concerned with being “sellable” than with the uncertainty of the profession when it comes to steady work. For an Asian-American actor faced with regrettably limited prospects, the proposition of finding more jobs is especially daunting — not to mention that the lack of starring roles makes it that much harder to stand out and get offers, particularly in an industry that continues to show a preference for white faces.

“Ruthie Ann Miles has a Tony, and I’m still kind of worried for her. There’s no security,” said Corpuz. Without any guarantees, he stressed his anxiety over finding work right after The King and I closed — or even in the years that follow.

For context, Corpuz pointed to the 1996 revival of The King and I, which was the first and last Broadway show for some Asian-American performers. “People who were the leads in the ’96 revival — the Tuptim and the Lady Thiang — I literally have no idea where they are,” Corpuz said.

He’s not alone in losing track of these actors: Tuptim was played by Joohee Choi and Lady Thiang by Taewon Yi Kim, both of whom have not worked on Broadway again since the revival. Kim told BuzzFeed News in a recent phone interview that after doing The King and I in the West End, she considered giving Broadway another go, but her agent recommended she focus her attention elsewhere. “With Asians at the time, there were not that many roles available,” said Kim, who has worked consistently in South Korea over the past 20 years in shows like Mamma Mia, The Sound of Music, and Urinetown. “We decided that maybe it would be better for me to stay in Korea for a while.” If presented with the opportunity, however, she said she would gladly return to New York.

“People do King and I over and over, because that’s all there is, or they don’t go back to Broadway,” Corpuz said. And while he feels a connection with the show and his character — a role he had previously played in other, non-Broadway productions — he stressed his ambitions to do something different.

“It’s almost painful to me to hear people say to me, ‘Oh my god, you’re gonna be a great King some day,’” Corpuz continued. “Maybe I would like to do that, but that’s the only thing you can see me doing? I don’t want to be spoiled, but I would like to do something else. … When am I gonna be given that opportunity?”

Ruthie Ann Miles and the cast of The King and I performing at the Tony Awards on June 7, 2015. Theo Wargo / Getty Images

here are a couple other less popular musicals that show up repeatedly on the résumés of Asian-American actors: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song, last revived in 2002 with a more socially conscious book rewritten by Hwang; and Stephen Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures, which will get an off-Broadway revival next spring with direction from Sondheim innovator John Doyle. In their original incarnations, these shows were written from a non-Asian perspective, though they do certainly open up casting opportunities.

Leung has performed in both. From his perspective, there are more Asian-American actors auditioning on Broadway than ever before, some of them bonafide stars, but “there aren’t that many roles being created for me,” he said. “The numbers are kind of against me.”

As Aladdin’s Adam Jacobs reflected, “Roles are coming in, but they’re just not coming in at the rate that it needs to happen.”

Theater is a risky investment, and a show like The King and I has a demonstrated ability to sell out Broadway’s 1,000-seat-plus theaters. There will be more revivals of The King and I and Miss Saigon “because we know it works,” Leung said. “We know that it sells tickets, and there’s a brand familiarity there.”

What we’re not getting on Broadway, besides the rare Allegiance, are new shows featuring original stories centered on Asian and Asian-American characters, and certainly not shows that divert from the insidious white savior storyline. Equally unique are shows in which a character’s Asian identity is both explicit in the script and not a propelling force for the plot — a show about Asians in America that isn’t a thematic battle between East and West.

“People have not trained themselves to see Asian-Americans in the same way they’ve trained themselves to see other groups. And that has a snowball effect,” Quill said.

Until the day Broadway offers ample and eclectic shows that are more inclusive, actors have to choose their battles. Turning down an audition or a part is a luxury, particularly when just getting in the room to be seen can be a challenge. Reed said that she gets called in for non-specified and ethnically ambiguous parts — she has played different ethnicities in the past, including in Miranda’s In the Heights. When it comes to the former, however, these roles are often assumed to be white.

“I would love to play Elle Woods. That’s a perfect example of something that I would love to do,” Reed said of the Legally Blonde protagonist. “They’re never gonna cast me as Elle Woods, like ever.”

Reed praised her agents for sending her out for traditionally “white roles,” although she said that in her own career, she has only ever been cast in parts that were, by her estimation, “ethnically right” for her. Her management team is more hopeful than she is when it comes to changing casting directors’ minds. “I want to believe that every time! But most cases, you don’t.”

“People have not trained themselves to see Asian-Americans in the same way they’ve trained themselves to see other groups.”

Leung is a firm believer in the power of a good audition. “An audition is a group of people needing to solve a problem — they need to find an actor to fill a role. And you just have to walk in and be that solution and go, ‘I am Chinese, I am 5’9, there are things that I can’t change about me,’” Leung said. “‘This is how tall I am, this is my skin color, but those things will not impede me from solving your problem, which is that you need an actor for this role, and I am a valid choice.’”

When Corpuz spoke to BuzzFeed News shortly before The King and I closed this past summer, he admitted some dread about jumping back into that audition process, which wavers between encouraging and deflating. The roles he’s been called in for are largely those that “comment on [his] race” in the form of a stereotypical role or a heavy “Asian” accent.

Corpuz felt heartened, however, when he was invited to audition for the Tony Award-winning play The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time as the lead Christopher, a role originated by a white actor. But not getting cast led him to speculate as to why: maybe he was too young, he surmised, or maybe he was too Asian. It’s pure conjecture, but imagining himself disqualified based on his race is a tough notion to contend with and an even tougher one to prove. Casting directors can’t even legally ask an actor about their racial and ethnic background, and may not cast an actor for any number of reasons unrelated to the color of their skin. “It is art and it’s subjective,” Leung offered.

Reed described a recent audition for which she was certain she’d at least get a callback, but didn’t. “At that point, you’re like, It has nothing to do with my performance,” she said. “Obviously they loved it — they were so complimentary — but it probably is gonna come down to the fact that they want a Caucasian girl for that specific part.”

roadway is a business, and it’s that cold, hard monetary reality that makes change in theater so hard to effect. Producers, who tend to be older and whiter, know what has worked in the past, and they want to replicate that success. This is an industry replete with hazards: Even established properties can fail. (American Psycho — which was a hit in the UK and is based on a popular novel that also spawned a movie — ran for only 54 performances earlier this year.) A study of Broadway musicals from 1994 to 2014 showed that a staggering 79% of all shows didn’t recoup their costs.

When it comes to Asian-led shows, there are even fewer examples of financially and critically successful productions to choose from, which may make it seem — to some financiers — that it’s because of the characters’ race. Allegiance, for example, had only 111 performances, not a flop but hardly a mainstream success.

“I’ve actually had producers say to my face, ‘Well, there’s no Asian shows on Broadway because they don’t sell. Asians don’t sell tickets,’” Leung said. “That’s the most crazy, insane, racist statement I’ve ever heard in my entire life, and somehow, that’s allowed to be said in our world. They’ve said it to my face.”

Unlike Leung, Hwang said no producers have directly told him that shows made by, about, and for Asian-Americans “don’t sell” (and he stressed that, if someone did, that conversation would not end well). But he argued that most producers are operating based on an outdated notion of what “works.” In other mediums, he noted, color-conscious casting has paid off handsomely. On television, for example, the dominance of Shonda Rhimes and the success of Empire have helped prove that people of color are clamoring to see more of themselves.

“I’ve had producers say, ‘Well, there’s no Asian shows on Broadway because they don’t sell.’”

Racial and ethnic representation in theater may be on the rise, but not fast enough to keep up with growing populations of people of color. Hwang suggested that in a country that will have a non-white majority by 2040, the overwhelming whiteness of theater is a “bad business model.”

“Those of us who are advocating for more diversity in these fields are actually saving these industries from themselves,” he said. “We are actually advocating a course which is not only more right in a political-social sense but also more commercially viable.”

As Quill noted, Asian-Americans have more disposable income than any other minority group, and that’s a market that’s largely been overlooked. People — both theater fans and Asian-American actors themselves — will buy tickets to support good representation.

Ali Ewoldt in The Phantom of the Opera. Matthew Murphy / The Phantom of the Opera

When someone does break through, like Ewoldt as the first Asian-American Christine on Broadway, “it’s a win for all of us,” Leung said. There’s a sense of camaraderie within the community, even with the dearth of available roles. “We all know Ali, we love her and we respect her work, and we know that she is up there eight times a week, representing our community in the best possible light and opening eyes and changing minds,” he added.

There are practical reasons to support Asian-American talent as well: Audiences tell producers what they want to see more of with the tickets they buy. Asian-American actors who see shows featuring other Asian-American actors increase the likelihood that more of these shows will be produced, creating more opportunities for everyone within the community.

And it goes both ways. Consciously boycotting a show that has no Asian representation is an act of protest: “What other power do I have?” Corpuz asked. He said he’s spent much of his life being asked to relate to white characters onstage, while white audiences are rarely tasked with doing the same work when it comes to Asian characters.

Quill shares a similar mindset. “I just need to not buy a ticket,” she said. “That’s how I vote. I vote buying a ticket or not buying a ticket.”

Jon Viktor Corpuz performing in New York City on March 2, 2016. Brad Barket / Getty Images

n the meantime, some performers are turning their attention elsewhere. Corpuz has been using much of his spare time to write, a skill he never thought he would have to cultivate. But if he’s not writing roles for himself, he’s concerned that he might just be out of work. “I have to divide my time between [acting] and writing because I have to be prolific on top of everything,” he said. “Which is honestly not a bad thing … but it’s more necessity than anything else.”

Actors have been emboldened to speak up about their experiences, and the diversity conversation, flawed though it may be, is at a steady roar. It’s forced established, stodgy producers to confront their biases and accept the reality of profitable theater starring non-white leads. On social media, people are now speaking up against whitewashing — take, for example, the mostly white Prince of Egypt concert that was canceled following backlash to its casting.

A few of the actors BuzzFeed News spoke to admitted that they were tired of talking about diversity, but they also acknowledged how essential it is to keep making their voices heard — both on social media and in the rehearsal room. Part of what made the most recent production of The King and I so progressive was that the actors involved made sure to air their concerns over anything that felt like a stereotype early on in the rehearsal process: It was the performers who insisted that they develop accents that were authentically Thai, with some doing their own research to ground their characters in reality.

“It’s important that these issues are raised,” Kim said. “It’s not whining to describe your own experience. I think if you don’t speak up for yourself when you’re asked, then you’re actually doing more harm than good, because it’s a tacit agreement to keep the status quo.”

The question of how to make Broadway more inclusive for Asian-Americans doesn’t have an easy answer. The path from the Miss Saigon casting controversy to Allegiance and Broadway’s first Asian-American Christine has not been a straight ascent: New shows have emerged that challenge the paradigm alongside others that reinforce the norms, while yellowface regressions have dwindled in the face of collective outrage. However many milestones are reached, there will always be room for improvement.

But while there may not be one singular solution, Quill has a response to the so-called lack of Asian-American stars, which Miss Saigon’s original casting director credited with the decision to cast Jonathan Pryce as the Engineer. “You know what it takes to make an Asian-American movie star or an Asian-American Broadway star? It just takes casting them,” she said. “That’s literally it. It’s not even hard.” ●