Flip through rap radio in the last couple years, and patterns emerge. Between the bars of Future’s viral hit “Mask Off” — “Percocets / Molly, Percocets” — there might be Logic’s hit “1-800-273-8255,” describing suicidal thoughts, the title of the song itself the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone number. Lil Uzi Vert’s “XO Tour Llf3” details Xanax addiction and being pushed “to the edge” where he might “blow my brain out.” XXXTentacion raps about suicidal thoughts and simulated his own hanging in a recent video, as did rapper Father in his clip for “Suicide Party.” Mac Miller, Schoolboy Q, Isaiah Rashad, and Kevin Gates also have tracks dealing with narcotics abuse and the emotional woes caused by their indulgences.

Drug use and self-harm are hot topics in popular rap songs by chart-topping artists, and their simultaneous emergence is no coincidence, with each topic bearing a long history in a genre that’s typically dominated by black men.

“Self-medication is the name of the game in the culture of young black men in hip-hop,” Vic Mensa told BuzzFeed News in September. The Chicago emcee fought his way back from drug addiction after a season of depression and suicidal thoughts — which were brought on by prolonged use of pills among other substances. He raps about it in “There’s a Lot Going On.”

Kid Cudi wrote a letter to his fans in 2016 describing his own mental health issues and why they led him to rehab. “My anxiety and depression have ruled my life for as long as I can remember and I never leave the house because of it,” Cudi wrote. “I can’t make new friends because of it. I don’t trust anyone because of it and I’m tired of being held back in my life. I deserve to have peace. I deserve to be happy and smiling. Why not me?”

Joe Budden has been open about his addictive personality, and struggles with drug abuse on top of his own mood disorder. “As somebody who’s been suicidal and battled depression, I would like to see hip-hop address it more,” he said during Complex’s Everyday Struggle, an online show that he cohosts. “We’re so powerful as a culture … we move things. Enough of us have died from mental health issues for us to look into it. Most of these rappers are telling us what they’re going through and I try to listen for it.”

“As somebody who’s been suicidal and battled depression, I would like to see hip-hop address it more.”

From heroin and cocaine in jazz and R&B, to acid in funk, to marijuana and Ecstasy in hip-hop, narcotics have been a not-so-silent partner to the sound and the subjects in black music. In contemporary popular hip-hop, however, popping prescription pills like Xanax, Oxycontin, benzodiazepines, and MDMA along with lean — a mixture of soda and Actavis syrup (if you can find it) — have become a badge of honor in contemporary hip-hop as well as on mainstream radio. Songs like these highlight the connection between music, artists, and fans and how each reflects the other.

Hand in hand with the pill name-drops are health conditions — addiction, depression, chronic pain — that some prescription drugs are actually engineered to treat. The pill rap wave dovetails with the growing heroin epidemic on top of suicide becoming the number two cause of death in teens ages 15 to 19, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Hip-hop has moved from selling drugs to using drugs as a point of pride, and that arc tracks with amplified numbers of suicide and mental health concerns among hip-hop’s target audience. The tandem rise isn’t a quirky coincidence: It’s a serious cause for concern, if not only for the performers but also for fans. Hip-hop has more than a minor ailment — the culture’s got an addiction and it’s driving us mad.

Vic Mensa, Logic, Schoolboy Q, Mac Miller, Kid Cudi.

Rich Polk, Kevin Winter, Bennett Raglin, Christopher Polk, Bennett Raglin / Getty Images

Drinking, smoking weed, and selling cocaine became staples in hip-hop — lyrically, and in practice — beginning in the mid-1990s, epitomized in albums like Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt and Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die. Tales of South American suppliers, coke bricks, and depictions of grimy dealers in the trap — a colloquialism for a drug and/or stash house — pumped from speakers in songs like “Can’t Knock the Hustle.” By the late ‘90s and early 2000s, rappers like Ja Rule and 50 Cent moved on to include Ecstasy as a party drug in their lyrics, though the inclusion of pills rarely budged beyond that.

The affordable low-risk high of lean made the drink a drug of choice with Texas artists like DJ Screw, a pioneer of the “chopped and screwed” style that fit nicely with the beverage’s propensity for slowing down the world. Lean — aka “dirty Sprite,” “drank,” “syrup,” “sizzurp,” “purp,” and “barre” — started making its way into rhymes down South, evidenced by hits like Three 6 Mafia’s “Sippin on Some Sizzurp” and Jay Z’s “Big Pimpin’” featuring UGK in 2000 (the same year Screw died from codeine-related conditions). Lean’s popularity in the black music community began long before the age of hip-hop, as retired University of Texas Health Science Center professor Ronald Peters told Noisey: In the 1950s, Houston blues musicians mixed cough syrup with beer and wine coolers to get the high of Benadryl today without garnering police attention.

But all along the way in hip-hop’s history, there’s been the counternarrative about drugs, prescription or not. Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five told a cautionary tale about rap and drugs in 1984 with “White Lines (Don’t Don’t Do It),” and in 1988 and Public Enemy’s followed up with “Night of the Living Baseheads.” Cash Money Records founder Birdman’s (formerly Baby) regional 1993 track “I Need a Bag of Dope” with the 32 Golds celebrated his love for snorting heroin but then getting sick if he couldn’t score: “I started snortin’ and scratchin’ and throwing up.”

Southern hip-hop’s rise arguably crystallized in the national popularity of Baby’s protégé Lil Wayne around the release of 2004’s “Go D.J.” Along with his gravelly delivery, the rapper brought a lean-filled cup and a penchant for the rockstar lifestyle; as Wayne recorded his 2008 album Tha Carter III, that cup became a mainstay in his interviews. The unauthorized documentary The Carter revealed his escalating narcotic dependence and the havoc it caused. Musically, while other rappers rhymed about indulging in weed and Ecstasy and privately snorted cocaine, this film shows Wayne giddily mixing lean as his manager exasperatingly dealt with his artist in the grip of addiction.

Elsewhere, Lil Wayne cuts like “Me and My Drank” and “Viva La White Girl” blatantly described the New Orleans MC’s predilections — and it sounded great, unfortunately. Wayne also spoke to his lean dependency during an interview with MTV News in 2008, saying, “Everybody wants me to stop all this and all that. It ain’t that easy. … feels like death in your stomach when you stop doing that shit.” (Lil Wayne declined BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.)

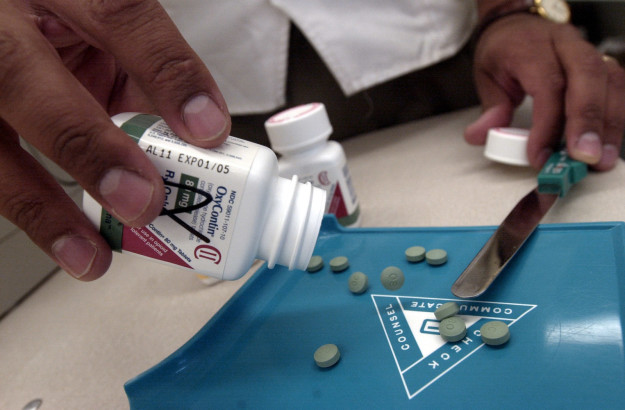

OxyContin

Darren Mccollester / Getty Images

Then came pills. In 1996, sufferers of chronic pain started getting prescriptions for a new drug called Oxycontin. A physician, Dr. Roneet Lev, chair of San Diego County Rx Drug Abuse Medical Task Force, told to Fox 5 San Diego that when Oxycontin hit the market, its parent company Purdue Pharma told doctors that only 1% of patients became addicted and furthermore that they were cruel if they didn’t prescribe it. In reality, addiction was much more prevalent, and ultimately helped to lead to America’s current opioid crisis, President Trump declaring it a national emergency in August. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the crisis was caused by three main variables: the huge jump of scripts written; “aggressive marketing” by pharmaceutical companies; and “greater social acceptability for using medications for different purposes.”

Elsewhere, Xanax, also known as happy pills, can be used to take the anxiety-ridden edge off other drugs like Ecstasy and soothe depression and unhappy feelings, making it a choice party drug. And thanks to pill mills, establishments where doctors loosely doled out prescriptions, drugs like Oxy, Vicodin, Percocet, and others weren’t too tough to get as long as one had the money. Users could cycle through several pill mills in one day to maintain their supply for personal use or for sale.

Speaking with BuzzFeed News, Ebro — host of New York’s Hot 97 morning show and Apple’s Beats 1 — wanted to clarify: Hip-hop didn’t start the pill-popping epidemic, that pills’ entry into rap’s vernacular is a reflection of whatever was already happening in United States specifically with youth culture.

Lil Wayne in “The Carter” documentary / Via vimeo.com

As artists like Lil Wayne rose in ranks in the mid-aughts, they “broke away from hood-centered paradigms in hip-hop culture,” said Langston Wilkins, ethnomusicologist and program officer with the State Humanities Council of Tennessee in Nashville. They brought with them “different cultural influences, whether it was Wayne’s skateboarding and pseudo-rock thing or Kanye’s high-fashion experiences. They also attracted different audiences and with them came different ways of partying or escaping your problems, like popping pills or tabs of Xanax and other drugs.”

Atlanta emcee Gucci Mane broke onto the larger hip-hop landscape in 2006 with “Pillz,” boasting a chorus asking “Is you rolling?” and him responding, “Bitch, I might be.”

“I was high as hell when I made ‘Pillz,’ and the next day when they played it, I was like, ‘Don’t do that,’ because it’s like I’m telling on myself!” said a now-sober Gucci during a recent event for YouTube in New York, speaking on his new book The Autobiography of Gucci Mane. “At the end of the day, I made millions but I was tripping.”

By 2011, Future debuted with his Dirty Sprite mixtape, directly shouting out lean, continuing on his career trajectory by touting drug use. As for his most recent summer hit “Mask Off,” he said in 2015 that all of the drug lingo is just for show. “I don’t have to do it all the time. I am sober,” he told Clique TV. “I’m not like super drugged out or a drug addict.” He raps about drugs, not because it’s his personal habit but “because I feel like that’s the number one thing everybody likes to talk about. … It’s the number one seller.” (Future declined BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.)

Future, Gucci Mane, Lil Uzi Vert, Kevin Gates, Chance the Rapper.

Kevin Winter, Bennett Raglin, Christopher Polk, Rachel Murray, Frazer Harrison / Getty Images

The CDC lists suicide as the #2 cause of death for teens in the US, sandwiched between homicides and unintentional injuries, which can include accidental overdoses. Historically, black people don’t often see therapists or doctors as much as we should, and like our ancestors who often took their issues to the Lord in prayer, rappers take theirs to the recording booth. Artists like Kendrick Lamar and Gates, who’ve both fought depression, have called music their therapy; however, it might also be good to also talk with a professional.

“There is something to be said for creative expression, but I wouldn’t say that’s enough,” said Inger Burnett-Zeigler, professor and clinical psychologist in Northwestern University’s department of psychiatry. “Therapy is really about identifying dysfunctional thoughts and how your feelings can be a product of that, and you need someone else to step in and identify that.”

According to the Handbook of African American Psychology, anxiety is the “most prevalent class of mental disorders in the United States” in terms of mental health for people of all ethnicities; 28% of people experience it at some point in their lives. Anxiety disorder includes “panic disorder, specific phobias, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),” demonstrated by persistent and debilitating fear. Anxiety is often flanked by depression and drug abuse, born as a way to tackle uncomfortable feelings. More than a few music artists may be exposed to nonprescribed medication when they’re on the road and maintaining a pace that allows them to consistently perform in front of thousands of screaming fans. But that pattern can be a slippery slope to unhealthy and addictive self-soothing habits.

Slaughter Gang/Epic