You have to salute the sheer, outlandish audacity of Darren Aronofsky.

In Mother! (which for readability’s sake we’re capitalizing, though the official title is all lower case) the filmmaker behind Black Swan and Requiem for a Dream enlists all kinds of horror, religious, historical, and home improvement imagery to tell a phantasmagoric allegory about how artists will never love another person the way they love their work. And right in the middle of this deranged howl of a new movie is his own current romantic partner, Jennifer Lawrence.

As an unnamed housewife, she’s subjected to an escalatingly nightmarish situation at the behest of her husband, an also unnamed older poet played by Javier Bardem. If Mother! reflects, in even the most roundabout way, how Aronofsky really feels about the tension between domesticity and the drive to create, Lawrence would do well to keep a copy of the film around as evidence in the case of a breakup.

At the start of the film, Lawrence and Bardem live alone in a house so remote it doesn’t seem to have a road leading up to it, much less any neighbors nearby. Nevertheless, a stranger played by Ed Harris turns up at their doorstep, claiming to have been told that the place is a bed and breakfast. It’s not, but Bardem invites Harris to stay for a drink anyway, and then to stay the night, and then as long as he wants, with the newcomer’s assessing, cold-eyed wife (Michelle Pfeiffer) showing up unannounced the next day to join him.

Lawrence, who’s been painstakingly restoring the once-burned house by hand while Bardem wrestles with writer’s block, is quietly shocked and hurt at her spouse’s sudden fit of hospitality, especially since he didn’t think of consulting her. Adding insult to injury, Harris and Pfeiffer are unapologetically crummy houseguests who smoke indoors and wander into private rooms, and who, it’s soon revealed, haven’t been up front about their reasons for coming. The truth is trickier — Harris knows Bardem’s work and is a huge fan.

So far, so unsettling, but all of it still relatively realistic, the unhappy Lawrence pinning on a polite smile and cleaning up after the entitled visitors who make a mess of her beloved home. Then more strangers start showing up, some of them violent and others just rude, making themselves comfortable in the house like a reverse The Exterminating Angel in which the guests can’t be made to leave. The sharp-eyed might notice these developments correspond to the Book of Genesis — Adam arrives first, then Eve, then Cain and Abel, and later, there’s even the home renovation equivalent of a flood.

Like the environmentally themed poem that was passed out before the film’s Toronto International Film Festival screening, this biblical symbolism is something of a red herring. Mother! doesn’t really parse as a religious fable or an ecological one, but elements of both swirl in the increasingly heavy atmosphere as Lawrence pleads with Bardem for a return to normalcy. She wants to go back to the private paradise she’s been trying to maintain for the two of them, and for the child she’s finally conceived. Bardem finally seems to hear her, and also starts writing again. And that’s when things start going epically off the rails.

A bloody wound inexplicably opens in the floorboards, and then a forbidding antechamber gets revealed in the basement. The health of the semi-organic ecosystem that is the house goes seriously downhill, and while newcomers keep coming through the door, reality leaves the film for good, the whole tumultuous history of humanity in miniature (swear to god) rushing in.

To describe the characters Bardem and Lawrence are playing as people isn’t really accurate — they’re types, jagged fragments of full personalities. Bardem is the artist as monstrous deity, creating universes and then destroying them to start over, starved for praise and forever pulling away from his partner to look outward for it and for new stories to use as inspiration.

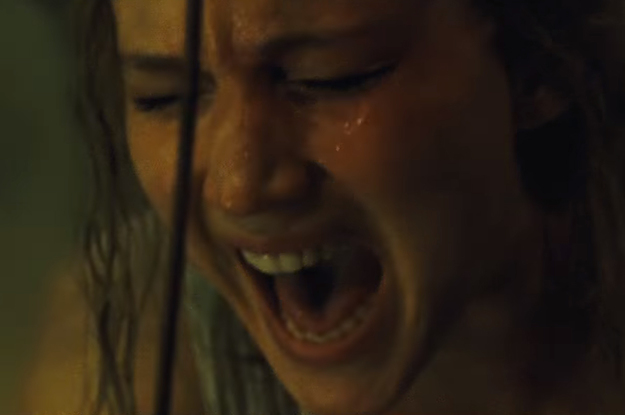

Lawrence is the perfect nurturer, a Giving Tree in the all-natural-fibers-clad body of a nubile 26-year-old, cooking and keeping house and desiring nothing more than to support and spend time with the husband who finds her attentions suffocating. Aronofsky’s regular cinematographer, Matthew Libatique, spends most of the movie with his camera up close to the Madonna-esque oval of Lawrence’s face, capturing flashes of betrayal, anger, and fear as her home is invaded by outsiders.

Mother! may be told through Lawrence’s character, but make no mistake, this is a movie about a man. More specifically, it’s a movie about a man whose need to create is a bottomless thing, a dissatisfaction that will always have him looking outward and prioritizing the attention of his audience over the person to whom he should be closest. That remains true even when members of that audience partake in an appalling version of a Eucharist that also happens to read like a filmmaker’s hyperbolic rendition of what it’s like to get work torn apart by critics.

The passive devotion that is the defining quality of Lawrence’s character might be maddening, but it ultimately reads less as reductive than as a way for Aronofsky to bolster his extremely unflattering but unapologetic case against his own stand-in. His urge to create art is portrayed as an insatiable hunger and such a fundamentally selfish restlessness that he chafes even against the most impossibly undemanding of partners. Her unqualified love can never satisfy him like his pursuit of the love of strangers.

Mother! is an art film getting a wide release, a fascinating (and maybe doomed), stylistically radical, thematically unfriendly, and admirably batshit gamble. It doesn’t tell a story so much as it feels like it offers a warped self-portrait of someone admitting there are limits to what they’re willing to give, but not what they’re willing to take, and in the end they can just begin again with someone else.

Though bathed in blood and tears and suffering — this disturbing abuse weathered almost entirely by Lawrence — Mother! isn’t remotely a traditional horror movie. But it is uncompromisingly horrific, in the way of listening to someone you know blurt out a bunch of ugly, unvarnished truths at the tail end of a drunken night. The honesty might be real and raw and compelling, but you’re also left having to figure out if you’ll ever be able to look at them the same way again.