When director Henry-Alex Rubin requested the FBI’s help with his 2012 cyber drama Disconnect, he wanted notes on the screenplay’s accuracy. But he suspected they wanted something more.

“They understand that perception is everything,” he told BuzzFeed News of the FBI. “The more they are perceived well, the easier their job is.”

He recalled that the FBI employee who reviewed the shooting draft of his film proposed changes to a scene in which two agents aggressively questioned a journalist.

“I remember distinctly the consultant saying to me, ‘This is not at all how we operate,’” he said. As Rubin recalled, the consultant told him that the FBI approaches people in a manner that “at least on the surface” is “kind and cooperative, and that attitude usually yields much more results than being suspicious or aggressive.”

Rubin changed the scene.

“If we don’t tell our story, then fools will gladly tell it for us.”

The director was right to think that the FBI is keenly concerned with its public perception: Hundreds of pages of FBI documents BuzzFeed News has obtained in response to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit reveal that the FBI actively seeks to control and burnish its image through consulting work on films. Over the past five years, the FBI’s Hollywood-focused Investigative Publicity and Public Affairs Unit has played a role in the development of hundreds of movies, television shows, and documentaries. Examples are varied, and include the newly released Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House, a biopic about the famous Watergate leaker Deep Throat; the 2012 straight-to-DVD Miley Cyrus romp So Undercover; and an episode of the docuseries Fatal Encounters. The bureau views these projects as marketing tools for an agency that desperately wants to build the FBI “brand,” the documents say.

“If we don’t tell our story, then fools will gladly tell it for us,” reads an August 2013 FBI PowerPoint slide advising bureau personnel how to use the media to their benefit. “Most people form their opinion of the FBI from pop culture, not a two-minute news story.”

The slide also includes this bullet point: “In any given week, Nielsen data indicates that FBI-themed dramas or documentaries reach 100,000,000+ people in the United States.” (Nielsen did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment on this data point.)

According to that slideshow, the FBI’s public affairs office — which acts as the liaison between the entertainment industry and the bureau — reviewed 728 requests for assistance on media ranging from novels to big-budget blockbusters in 2012 alone. FBI consultations are free for the filmmaker (although not for the taxpayer), and the consultations described in these documents ranged in scale from a cursory informational email exchange to “personnel and time intensive” multi-day shoots at the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, DC.

The majority of productions asked for something relatively small, like a quick fact-check or permission to use the FBI logo. In one brief consultation from March 2011, the FBI seriously considered a request from the screenwriter of the musical zombie horror-comedy Diamond Dead. The writer “was looking to put the FBI in a chase for zombies ‘just because’ in his [mind] he thought the fictitious FBI in his script would like to research the zombies,” an FBI employee wrote in the documents. “I advised him to try with someone like NIH, HHS, CDC, or another health/medical government agency as it would be of no interest to the FBI unless they committed a crime.”

The writer-producer who made that call, Andrew Gaty, told BuzzFeed News, “I always like to do fairly serious research,” recalling that he spoke with the staffer for a few minutes. “My basic question was, what would the FBI do if they found zombies?”

“My basic question was, what would the FBI do if they found zombies?”

The FBI doesn’t just field queries from filmmakers but also takes a proactive role when an opportunity arises to advance its own public relations interests. Indeed, a few years ago, an FBI agent was reading a Hollywood trade publication when the agent came upon a story about a movie that would star Sylvester Stallone as reputed mob enforcer and FBI informant Gregory Scarpa. The agent was intrigued and decided to reach out to Nicholas Pileggi, the Goodfellas scribe who was writing the Scarpa screenplay, to ask “if he wanted FBI input,” according to the FBI documents. Pileggi apparently was interested and told the FBI agent he would make contact when “he was ready to start the project.” Pileggi’s representative did not respond to a request for comment, and the film is still in development.

Christopher Allen, the Investigative Publicity and Public Affairs Unit chief, told BuzzFeed News that the FBI could not provide updated figures about the number of productions it has assisted with since 2013. But productions featuring the FBI continue at a rapid pace. Mark Felt was released Sept. 29. In October, Netflix will premiere Mindhunter — a series about FBI agents who study and track down serial killers — and CBS will air the 280th episode of its own serial-killer-catcher procedural, Criminal Minds. The Netflix series consulted directly with the FBI, and the former agent who wrote the book Mind Hunter, John E. Douglas, is a credited consultant on the show. Criminal Minds has also consulted with the bureau, and this season, an agent turned producer will have his 11th writing credit on the show.

Although the bureau explicitly says it “does not edit or approve [filmmakers’] work,” winning cooperation from the FBI often means portraying the bureau in a positive light. According to the documents, the FBI will sometimes deny permission to use the logo for reasons that border on petty: One film was turned down in 2008 because the FBI’s role in the movie was too small. And for certain projects — like the Silence of the Lambs trilogy, the 2009 Johnny Depp film Public Enemies, and 2007’s Live Free or Die Hard — the bureau will go to extraordinary lengths to assist production teams, assigning agents to answer questions on call or approving multi-day shoots on FBI grounds. Additionally, the bureau conducts semi-regular “FBI 101” workshops at the Writers Guild, instructing screenwriters on the ins and outs of working with the bureau; an invitation to one such event in June called it “your opportunity to engage the FBI directly.”

Matthew Cecil, a scholar of the FBI’s image, told BuzzFeed News that the FBI’s relationship with Hollywood dates back eight decades. The bureau’s PR strategies have been “remarkably” successful in advancing the FBI’s goal of making people “more comfortable with the idea of this extremely powerful agency.” Cecil, who wrote Branding Hoover’s FBI, distinguished the bureau’s branding from that of the CIA (which has an “entertainment industry liaison”): “They’ve never been good at it at all.”

The FBI is still secretive about how it interacts with Hollywood filmmakers. It took three years and a lawsuit to pry loose these documents. But nearly a dozen filmmakers who spoke to BuzzFeed News were mostly open and positive about the liaison. The majority recounted how deeply impressed they were by the thoroughness and professionalism of the FBI employees they interacted with. “They were highly intelligent, and they could see easily what the script was trying to say, and where it was going,” said Peter Woodward, who wrote the 2010 Samuel L. Jackson film Unthinkable.

Filmmakers explained that they contact the FBI because they want their work to be more realistic. “I have always found the FBI to be extremely and productively cooperative and open. … I’ve actually found them almost as eager understand the narrative I’m after as I am,” said Mark Felt writer-director and former journalist Peter Landesman.

But it’s clearly more than just an educational exercise for the bureau. Internally, the FBI says it has a “mission interest in developing the public image of the FBI and ensuring an accurate portrayal of FBI personnel, past and present, in order to encourage public cooperation with the FBI in performing its mission.” The documents show that the unit evaluates how high-profile a project is going to be before deciding to approve consultation, generally reserving their highest levels of assistance for projects expected to be blockbusters. The unit’s guidelines for requests specify that the agency needs to know “whether the project is ‘sold,’ ‘green lit,’ commissioned, or speculative.”

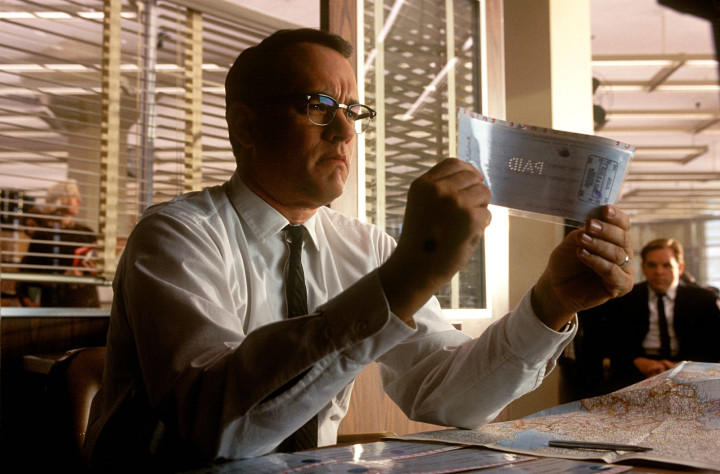

In one 44-page spreadsheet that logged more than 200 requests made between 2005 and 2014, Tom Hanks was name-dropped three times (for Captain Phillips, Parkland, and Mark Felt). In another document referring to the predicted blockbuster Live Free or Die Hard, the office acknowledged that the movie was not about the bureau — in the final film, FBI characters spend much of their screen time describing the havoc caused by hackers. And yet the Office of Public Affairs approved a two-day shoot at the J. Edgar Hoover Building involving around 400 extras; additionally, an agent from the Los Angeles office worked with the production “extensively, to include sitting in on production meetings.” In contrast, another project received a recommendation that “LIMITED ASSISTANCE BE PROVIDED AS THIS IS A FIRST TIME SCREENWRITER.”

Tom Hanks as FBI agent Carl Hanratty in the 2002 film Catch Me If You Can.

Dreamworks / ©DreamWorks / Courtesy Everett Collection

The FBI’s self-interest was evident to Ed Saxon, the Silence of the Lambs producer who was the bureau’s point person on the 1991 film. Saxon expressed some misgivings about the consulting arrangement. “We had political qualms about how closely we were working with the FBI and how much we were making the FBI look like heroes when the FBI’s history as an organ of the state has been complicated, to say the least,” he told BuzzFeed News.

In a nod to those reservations, director Jonathan Demme added a line to the film about the agency’s record of civil rights abuses, Saxon said. “To Jonathan in particular, it was important that he wasn’t just making a commercial for the United States police department.” The production team knew the FBI viewed the movie as a recruiting tool for female agents: “Our picture — with a heroic female agent, or agent trainee, at its center — lined up well with their goals,” the producer said.

Saxon’s take is more in line with internal records at the FBI. The bureau’s recommendations for cooperating with filmmakers generally emphasize a commitment to accuracy, but sometimes they refer directly to how the agency appears. A few documents stated that the goal was not only to support authentic depictions but favorable ones; one said, “Most of the time, Hollywood writers do not seek our input and oftentimes they get it wrong. So when given the opportunity to educate the writers/producers we have found we are in a better position to possibly have them portray the FBI in a positive light and with accuracy, or fairly close to accurate.”

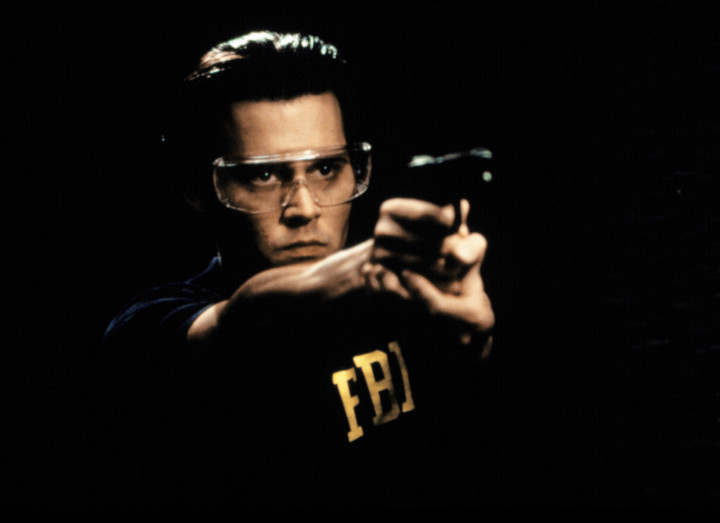

Johnny Depp in the 1997 film Donnie Brasco.

Sony Pictures / ©Sony Pictures / Courtesy Everett Collection

There are also hints that the bureau wants to remind the public that FBI employees are people, too. When the FBI recommended that personnel should be interviewed on camera for a special feature on the 2000 DVD release of Donnie Brasco, a document explained that “[t]he segment would satisfy the public’s desire to learn about the FBI by showing the human, personal side of an Agent’s job.”

The documents suggest that the ideal onscreen FBI character is approachable, polite, and not conducting surveillance. In April 2012, someone from the production of the Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson crime caper Empire State put in a request to use the FBI seal in the film on short notice. After the unit reviewed the script, the request was denied, in part because the script featured bureau personnel being rude to local law enforcement. “P. 70 had FBI agents rolling onto scene and immediately condescending NYPD,” the log says. “Also later in script agents were ‘dragging’ patrons out of restaurants and theaters…the script does not accurately portray FBI procedures and personnel and therefore use of official SEAL was declined via email on 4/27/2012.”

This position — preferring a restrained image of the bureau — was echoed in the recommendation for Public Enemies, which followed the hunt for a group of 1930s bank robbers. Although the FBI approved significant consulting on Public Enemies, a document noted that the film “‘heightens the image of the FBI as an agency seeking to win by whatever means necessary,’ not necessarily a flattering portrayal.”

And the FBI has long wanted to avoid associations with covert surveillance in particular. Wiretapping, as Cecil writes in Hoover’s FBI and the Fourth Estate, was expressly forbidden from the TV series that the bureau essentially coproduced in the ’60s and ’70s; that aversion continues to the present day. A request was declined in 2012 not only because a “[f]ictional agent has incredibly small role” but also because the agent was “not portrayed in best light (mostly through scare tactics of wiretapping and other surveillance).” And on the podcast Crime and Science Radio in 2015, FBI Public Affairs Specialist Betsy Glick said that bureau officials shaped fictional portrayals of the FBI because they don’t want people “getting a bunch of erroneous, negative, Big Brother–type messages from the media” — explicitly referring to the pervasive state surveillance in the book 1984.

“[I]f all the people see in the movies or in pop culture are negative and wrong antagonistic portrayals, they’re not gonna cooperate.”

Notably, one of the most prominent recent films that was critical of the FBI — 2014’s Selma, which portrays the bureau’s intense surveillance of civil rights hero Martin Luther King Jr. — relied on books, documentaries, and internal FBI documents, and not on consultation with the bureau itself. Director Ava DuVernay, who also rewrote the script, was not available for an interview, but her representative confirmed to BuzzFeed News that she never reached out to the FBI for assistance; neither did screenwriter Paul Webb, his representative said.

One screenwriter’s takeaway from an FBI seminar held at the Writers Guild — that the FBI largely worked with filmmakers because the agency wants to seem friendly and approachable — was repeated by Glick on the podcast. “How does the FBI solve crimes?” she asked. Glick answered her own question: “We solve crimes when people are willing to talk to an agent when he knocks on their door, and if all the people see in the movies or in pop culture are negative and wrong antagonistic portrayals, they’re not gonna cooperate. Our mission is to build the trust of the American people so that they can help us solve our operational mission.” ●