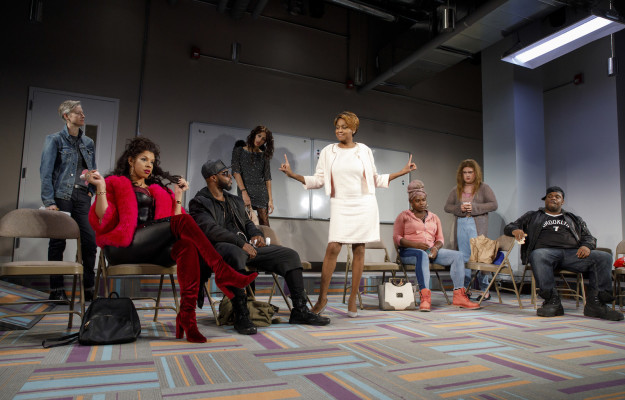

The cast of MCC’s Charm at the Lucille Lortel Theatre.

Joan Marcus

We might not think of etiquette as gendered, but it is — the manners we’re taught at a young age often rely on a traditional conception of what boys and girls ought to do. In the more progressive, less binary world of 2017, that can be stifling, if not archaic. But it doesn’t have to be that way, according to Will Davis, director of the off-Broadway play Charm.

In working on the play, about a charm class for young queer people, Davis discovered a way to shake his negative connotations of etiquette. “There’s this other definition and way to look at it, which is about deep empathy,” he told BuzzFeed News from the mezzanine of the Lucille Lortel Theatre in the West Village, where Charm opened on Sept. 18. “There’s another perspective to look at it from, which is ways in which you can think to prepare a space for somebody else. And that just really struck me as being powerful, a way to combat a sense of divisiveness.”

Charm not only gives audiences a new way to think about good manners; the play also offers new perspectives on gender identity, and the way trans lives can and should be represented onstage. For Davis, who is trans, Charm reflects an essential conversation about inclusion in theater — and, ideally, a way forward.

“I wanted to be an artistic director because I wanted to up my activism.”

Written by Philip Dawkins, the play was inspired by the true story of Miss Gloria Allen and her work teaching etiquette at the Center on Halsted, an LGBT community center in Chicago. Here, Allen becomes Mama Darleena Andrews, played in the MCC Theater production by Sandra Caldwell, who booked the role after auditioning as an openly trans woman for the first time. Charm depicts Mama’s attempts to connect with the young queer people she calls “babies,” and the generational divide that informs their radically different perspectives. The babies represent a wide spectrum of gender identities — not to mention racial identities and class backgrounds that reflect the diversity of the trans experience — and the cast features the same gender diversity.

“A piece like this that has the potential to be such a vehicle and such a platform for trans-identified actors, there is a big responsibility that I felt, and I know all of MCC felt, to make sure that we got actors whose identities aligned with the characters,” Davis said. “That has not always been true in other productions of this play, and it was, for me, a requirement in order to agree to do this show.”

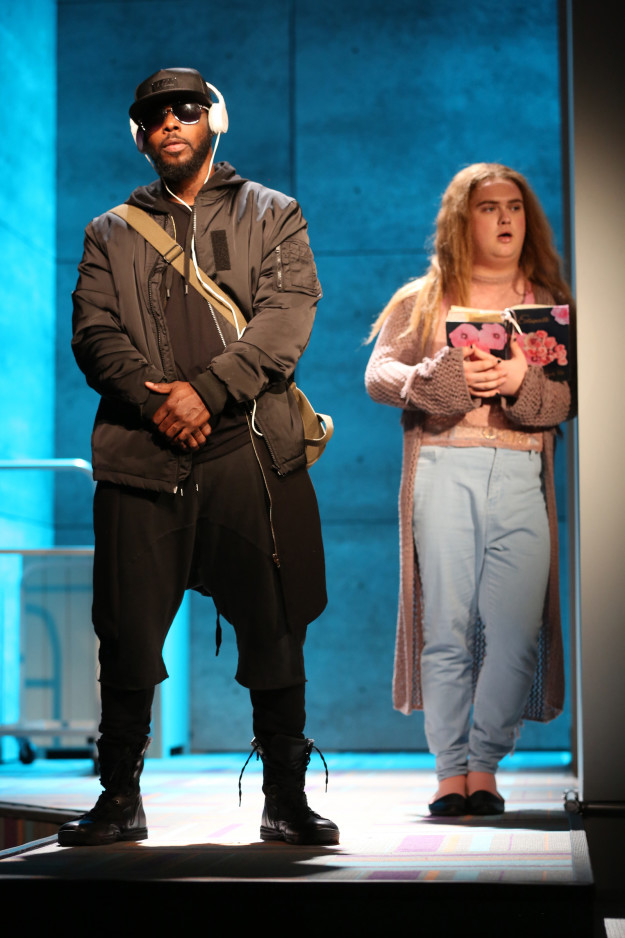

Beta (Marquise Vilson) and Lady (Marky Irene Diven).

Joan Marcus

Davis was prepared to have a conversation about why Charm had to be cast the way it was; fortunately, MCC was committed from the beginning. But while there appears to be more of a push for authenticity and inclusion in theatrical casting across the board, countless productions still struggle — or fail to even try — casting appropriately when it comes to gender identity. The use of cis actors in trans roles also remains a regular practice in film and television, where actors like The Danish Girl’s Eddie Redmayne and Transparent’s Jeffrey Tambor have earned accolades for playing trans women.

The excuse often used by producers for this lack of representation is that trans actors are hard to find or untrained, something that makes Davis “incredibly angry” to hear. “That’s been said about every marginalized group of actors ever. That’s not particular to queer and trans folks. That’s particular to actors of color, to women,” he said. “If you’re in a position in which you’re saying that, that actually means the responsibility for finding them and training them lies with you.”

Davis acknowledged that casting Charm did require putting in the effort and thinking outside of the box. He connected with activists and others who work in the queer community in order to bring in trans-identifying performers who might not have representation or even professional acting experience. And while he’s usually opposed to video auditions, he made an exception for actors who weren’t able to travel to New York and try out in person.

“It felt like, let us work every angle,” Davis said. “We’ll jump [through] the hoops instead of asking this other population to do that.”

From left to right: Logan (Michael Lorz), Ariela (Hailie Sahar), Mama (Sandra Caldwell), Victoria (Lauren F. Walker), Donnie (Michael David Baldwin), and Jonelle (Jojo Brown).

Joan Marcus

As the artistic director of Chicago’s American Theater Company, Davis is the first trans person to run a significant arts institution in the US. He takes that responsibility seriously, not only in terms of the way he casts his shows but also in how he continues to be outspoken about inclusion and representation. Discrimination in the theater community, whether conscious or not, is a very real problem, and there are those who avoid speaking out for fear of reprisal. That’s all the more reason why he is “as vocal as possible.”

“I wanted to be an artistic director because I wanted to up my activism,” Davis said. “I have the ability in conversation with the playwright and the producer and everyone to make decisions about the bodies onstage. I don’t want to let anyone down.”

Mama (Caldwell) and Ariela (Sahar).

Joan Marcus

For Davis, activism also means challenging the dominant perspective on what sells and what doesn’t. Mainstream theater is often so concerned with appealing to a wide audience that stories about marginalized communities fall to the wayside. Plays about queer people may find a home downtown, but they rarely make it to a big Broadway theater. And Charm isn’t just a story with trans characters — it’s a play that actively engages with generational divides within the trans community. Mama encourages the youths she’s mentoring to stick to one gender presentation to avoid confusing nontrans people, and she struggles to come to terms with a more modern conception of gender fluidity and pronouns.

Just as Mama worries about the trans community alienating straight cis people, less daring theatrical producers and directors might be concerned about turning off subscribers with a play that dives deep into the ever-changing politics of trans identity. But Davis notes that the success of Charm lies in its specificity: The play is relatable in part because it is grounded in the real, lived experiences of trans people, and that includes debating complicated questions about terminology and gender expression. In a larger sense, Davis is tired of being told that some theater — and it’s almost always theater about marginalized groups — isn’t sellable.

“Folks leaving this process are going to enrich the landscape of the American theater.”

“Whether people are conscious of it or not, they’re telling me that non-straight white narratives don’t have worth if they’re saying that won’t sell or if they’re saying that’s alienating to an audience,” Davis said. “They’re telling me that the people who represent a non-cis white world are not of value.”

As frustrating as the theater community can be at times, Davis has had plenty of successes, and Charm continues to be an immensely rewarding experience for him. He’s optimistic about the future of trans representation onstage, particularly if more people — including people from different backgrounds than his — are able to make themselves heard. And, of course, if those in positions of power are willing to listen and adapt.

Davis believes there will always be plays like Charm, works that are in conversation with a contemporary cultural moment. But going forward, he also hopes that theater can broaden its perception of the classics in the canon, and who gets to play those roles. He’s been “deeply touched” watching the actors in Charm bloom, and he knows they can continue to do great work — whether in plays about trans identity or not.

“I’m so excited about this show, this production of this show, but in a way, I’m also almost more excited about what these actors are gonna get to do after this show because they have been provided resources they haven’t had in the past,” Davis said. “I’m a firm believer that a rising tide lifts all boats. … Folks leaving this process are going to enrich the landscape of the American theater because of the things that this production could provide for them.”