The Red Dress for BuzzFeed News

When it comes to slasher villains of the ‘80s, Chucky stands alongside Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, and Michael Myers as the most iconic — just several feet below. But while Freddy and his Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, Jason and the Friday the 13th movies, and Michael and the Halloween series have endured countless reboots, revivals, stars, and filmmakers over the past few decades, Chucky has remained under the control of his creator, Don Mancini, who has written every entry in the franchise since cowriting Child’s Play in 1988. He’s also been voiced by the same actor, Brad Dourif — and terrorized many of the same costars — in each installment. That’s not just rare for a slasher series: It’s unprecedented.

The pint-sized redhead doll possessed by the spirit of a serial killer may not have gone to space like Jason Voorhees or tussled with Tyra Banks like Michael Myers, but he has seen some wild shifts over the years. Over the past three decades, the Child’s Play series has transitioned from horror to comedy and back to horror again, and Chucky himself has been the villain, the antihero, and yes, even the romantic lead. That’s because Mancini is as committed to retaining his hold on the series as he is to never doing the same thing twice.

“Any good story is about surprising the viewer and subverting their expectations,” Mancini said. “With sequels, you have a unique opportunity to do that because people come to a sequel or remake with very specific expectations. So it’s like, how can I fuck with that?”

The most consistent thing about the seven-film Child’s Play franchise is that it’s constantly reinventing itself — not as a result of studio intervention, but because of Mancini’s drive to keep audiences on their toes. In a genre that has been derided for being repetitive, Chucky stands alone.

BuzzFeed News sat down with Mancini to talk about the series’ humble beginnings, its growing pains, and how to keep a franchise going without losing an audience who has seen it all. From Child’s Play in 1988 to Cult of Chucky, now streaming, this is an inside look at one of horror’s most dynamic icons.

Child’s Play (1988): “Hi, I’m Chucky, and I’m your friend till the end.”

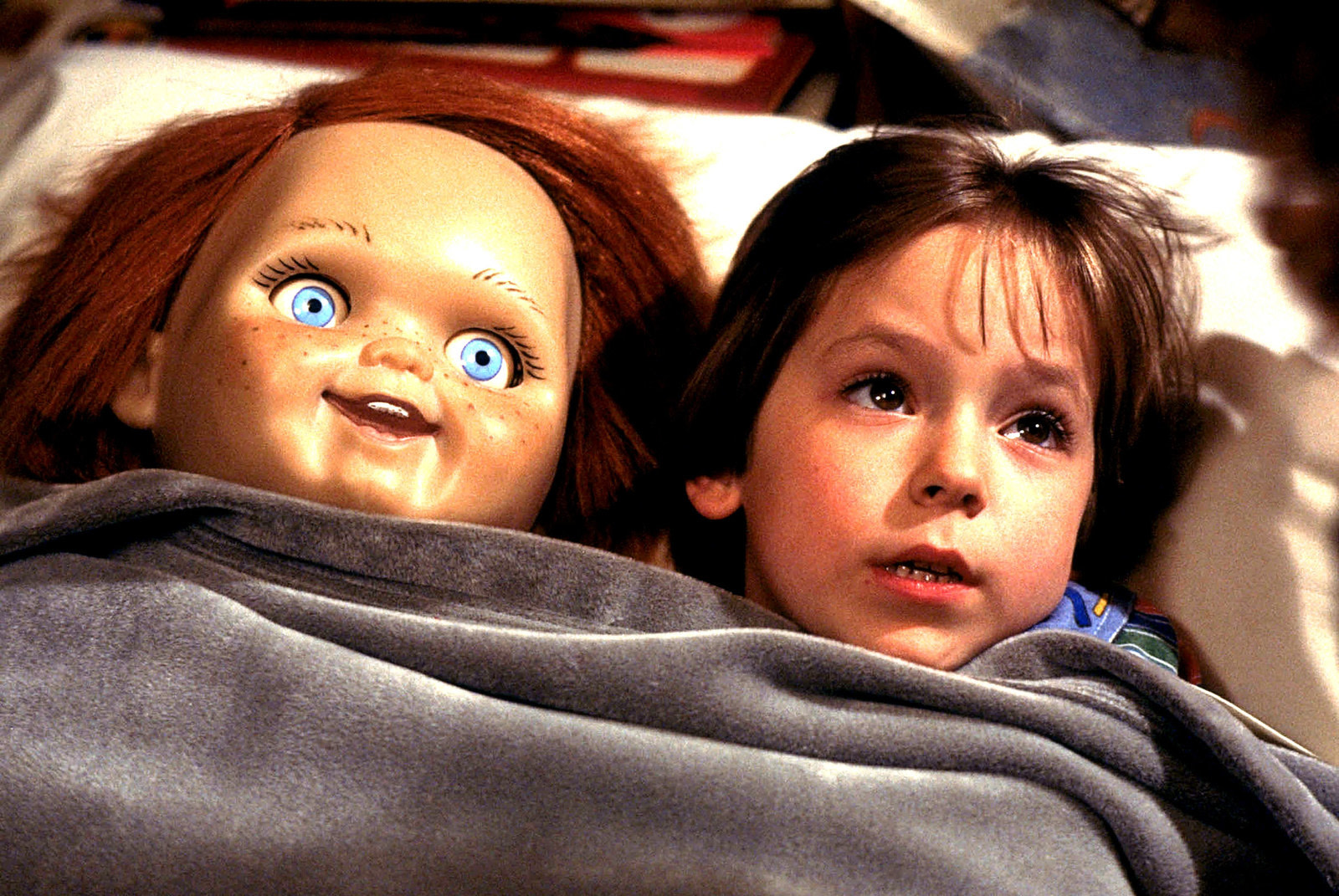

Chucky and Andy Barclay (Alex Vincent) in Child’s Play.

United Artists / Courtesy Everett Collection

In retrospect, the first Child’s Play is almost quaint in its restraint — that is, as restrained as a movie about a killer doll can be. The film follows 6-year-old Andy Barclay (Alex Vincent), who has no idea that the Good Guy doll he’s been gifted for his birthday has been imbued with the spirit of sadistic serial killer Charles Lee Ray (Dourif). As the body count rises, Andy’s mother Karen (Catherine Hicks) and homicide detective Mike Norris (Chris Sarandon) begin to suspect that the young boy is a budding psychopath.

In Mancini’s original script, which he wrote as a film student at UCLA, Andy was inadvertently responsible for the murders: Chucky was actually a manifestation of Andy’s id. Mancini described the film as “a dark satire about how marketing affects children,” inspired by his father’s career in marketing. “I had already formed a pretty cynical perspective on that whole cult,” he said.

But after United Artists, a subsidiary of MGM, picked up the movie, Child’s Play underwent some significant changes. Director Tom Holland worked on a new version of the script alongside screenwriter John Lafia, and the focus shifted from the fragile psyche of a child to the (relatively) more straightforward story of a serial killer trying to get out of a tiny plastic body. The new creative team also dropped Chucky’s singsong doll voice in favor of Dourif’s Chicago rasp, and added some supernatural mythology. “I can’t be completely objective about it, because of some of the changes they made,” Mancini said. “I really hate the voodoo. I hate the chant. I hate all of that.”

Despite Mancini’s objections, Child’s Play was a major hit, earning over $33 million at the US box office on a $9 million budget. Chucky quickly emerged as a new horror icon, notable for the way he stood out from his slasher villain contemporaries. In his review, Roger Ebert said that the film “succeeded in creating a truly malevolent doll. Chucky is one mean SOB.”

Mancini may have had a slightly different idea for the killer doll when he first wrote the script, but this Chucky matched his goal of designing a character who would surprise audiences. “I was excited about the prospect of creating a horror villain that went in the opposite direction — in terms of just their physical presence — than what was popular at the time, which was Freddy, Jason, and Michael Myers,” he said. “They’re all these big, hulking guys who just sort of relentlessly come after you.”

Chucky was his own beast — his closest relative would be Freddy, who shared his penchant for wisecracking; the others were the strong, silent types. And yet, there was at least one other thing Chucky had in common with the others — despite his apparent death at the end of the first movie, he was instantly poised for a sequel.

Child’s Play 2 (1990): “Wherever I go, Chucky will find me.”

Chucky and Andy (Vincent) at the Good Guy factory in Child’s Play 2.

David Kirschner / Kobal / REX / Shutterstock

The success of Child’s Play meant that Mancini didn’t have much downtime: He started working on a sequel within a couple weeks of the first movie’s debut. “It happened really fast,” he recalled. “The movie was a hit and they wanted to develop a sequel very quickly.”

Mancini didn’t love that he had to follow the mythology added to the first film — in order to return to human form, Chucky can only transfer his soul to Andy, the first person he revealed his true self to — but he admitted that the “contrivance” was “very narratively useful.” And it positioned Andy as the franchise’s final girl, the last survivor in a slasher film and a role usually given to a teenage girl.

Even with the second movie, which was distributed by Universal Pictures, Mancini was already worried about repeating himself. “When you do sequels, it’s always tricky because you … definitely don’t want to do the same movie,” he said. “You have to give people what they want — but at the same time, spin it.”

To avoid simply making Child’s Play again, Mancini ditched the original adult characters, Karen Barclay and Mike Norris. In Child’s Play 2, Vincent returned as Andy Barclay, but he would be living with foster parents Phil (Gerrit Graham) and Joanne Simpson (Jenny Agutter) and a foster sister, Kyle (Christine Elise) — of course, he was still being pursued by the same malevolent doll. Mancini also reintroduced some of the elements that had been removed from his original script for Child’s Play, including a visit to the factory where Good Guy dolls are assembled.

And he continued to lean into the humor that made Chucky a sassier alternative to the muted killers who usually stalked horny teens in slasher movies. “Certainly there was some serious camp,” Dourif said. “It wasn’t a straight horror movie about a doll. Chucky was funny. He took his killings lightly.”

With Child’s Play 2, which grossed $28.5 million in the US on a $13 million budget, Chucky was becoming a sort of hero in his own right. While his victims were never as disposable as those in other slasher series are, Chucky himself was clearly the selling point. As one review noted, “There reaches a point at which one can’t help but be drawn into Chucky’s predictably murderous shenanigans.”

“Chucky had been embraced by the pop culture zeitgeist to the degree that he was kind of beloved,” Mancini said. “He was already a bit of an antihero, and part of the way he worked was by bucking the status quo.” And that gave Mancini the idea for the next sequel. In hindsight, it wasn’t a great one.

Child’s Play 3 (1991): “Grow up, Barclay. It’s time to forget these fantasies of killer dolls.”

An older Andy (Justin Whalin), still being terrorized by Chucky in Child’s Play 3.

Rights Managed / Universal Pictures / Ronald Grant Archive / Mary Evans

In Child’s Play 3, Chucky is still after Andy, but the troubled kid at the heart of the first two movies has aged up to 16 and the action has relocated to Kent Military Academy, where Andy (now played by actor Justin Whalin) is a cadet. The idea, as Mancini envisioned it, was to pit his antiestablishment killer doll against the conservative, ordered ideology of the military school and its cruel authority figures.

Child’s Play 3 came out in August 1991, just nine months after Child’s Play 2, and it failed to resonate with either audiences or critics. The film earned the worst reviews of any in the franchise, with a Rotten Tomatoes score of 23%. Entertainment Weekly gave it an F, with critic Owen Gleiberman writing, “The plastic slasher proves that his novelty value has long worn off.”

Mancini doesn’t entirely disagree. He describes Child’s Play 3 as “the weakest of the films, and really it’s all down to the script”: “Despite aging Andy, despite putting it in this new milieu, I think it felt a little tired,” Mancini said. “In retrospect, I think I could have used a breather. But you also get stuck in your own bubble, and [think], This is great. And they just wanted another movie to come out quickly.”

Even if Child’s Play 3 was largely a failure, it underscored Mancini’s willingness to try something new to prevent the series from growing stale. It also reflected a problem that Chucky’s predecessors — namely Freddy Krueger — had faced: Eventually, the killer stops being scary.

“The more you see, the less scary they are,” Mancini said. “And in our case, with Chucky, it’s an even bigger problem — it’s absurd to begin with because he’s so little.” He tried to solve that by keeping Chucky in the shadows for some of Child’s Play 3 and focusing on new characters, but audiences were hungry for more Chucky, not less — particularly after advancements in technology allowed the character to stand on his own. Even the Washington Post’s overwhelmingly negative review called Chucky an “animatronic delight.”

The year after Child’s Play 3, Universal made Chucky a permanent installment at their annual Halloween Horror Nights event. Fans would line up for the “Chucky’s In-Your-Face Insults” for a chance at being read for filth by a killer doll.

For the next sequel, Mancini knew he had to put Chucky front and center, and his solution was to move into another genre entirely.

Bride of Chucky (1998): “Barbie, eat your heart out.”

Chucky and Tiffany in Bride of Chucky.

Mca Universal / Courtesy Everett Collection

The downside to Chucky’s mainstream appeal was that the villain, once the stuff of nightmares, had clearly become more amusing than menacing to many people. “You just have to find ways of embracing that and subverting it; so obviously when we did Bride of Chucky, we decided to swing out the wave and embrace the absurdity,” Mancini said.

It took seven years before Chucky returned for his fourth movie, Bride of Chucky, which ditched the Child’s Play title and the character of Andy Barclay entirely. Inspired by the classic film Bride of Frankenstein — the title is an obvious homage — the movie sees Charles Lee Ray’s girlfriend Tiffany Valentine (Jennifer Tilly) transformed into a doll of her own. Together, the dolls join forces to possess the bodies of two new victims, Jesse (Nick Stabile) and his girlfriend Jade (Katherine Heigl). Along the way, Chucky and Tiffany bicker, fall in love, and — in a truly surreal moment — get hot and heavy, somehow getting Tiffany pregnant. (The less you think about the logistics, the better.)

Just as Bride of Frankenstein brought a touch of humor to the Universal Monsters series, Bride of Chucky was the funniest installment yet in the Child’s Play franchise. Mancini conceived of the film as a twisted romantic comedy, as much about Chucky and Tiffany’s dysfunctional relationship as it was about their murder spree. “Chucky’s a very versatile figure and you can plug him into different genres,” Mancini said. “If we make it a comedy [and] bring him to the center and make him the lead of the movie, you’re just making a different kind of movie. But that’s a legitimate kind of movie.”

And Bride of Chucky was the biggest departure from the original Child’s Play, but it was very much in step with the era of the new, more meta slasher ushered in by Scream in 1996. In addition to the heightened comedy, Bride of Chucky reinvigorated the franchise by introducing Tiffany, a character Mancini had written specifically for Tilly.

“I was a little bit reluctant because I had never done a horror film before, and I kind of had some weird idea that horror film was something you did at the beginning of your career or the end of your career,” Tilly recalled.

Tilly ended up being convinced by the script — and some encouragement from her former Bound costar Gina Gershon. Tilly’s presence as a gay icon, thanks largely to Bound, gave Bride of Chucky a stronger queer sensibility, something Mancini, who is gay, had been angling for. He also introduced (and then killed off) the first gay character in the franchise, Jesse and Nick’s friend David (Gordon Michael Woolvett).

“I was sort of consciously injecting some gay identity into it, and people really embraced that,” Mancini said. “I think it’s important — in addition to being fun — because you just don’t see it much in the horror genre. … One of the distinguishing factors of our franchise is that it has a certain gay identity.”

Critics were still divided on Bride of Chucky, but the box office was strong: The film grossed over $50 million worldwide on a $25 million budget. Audiences seemed to love it, and the largely positive response to a funnier, queerer Chucky movie delighted Mancini. In fact, he was “so emboldened by it” that he “went insane on Seed of Chucky.”

Seed of Chucky (2004): “This is nuts, and I have a very high tolerance for nuts.”

Tiffany and Chucky are joined by Glen in Seed of Chucky.

Rogue Pictures / Via youtube.com