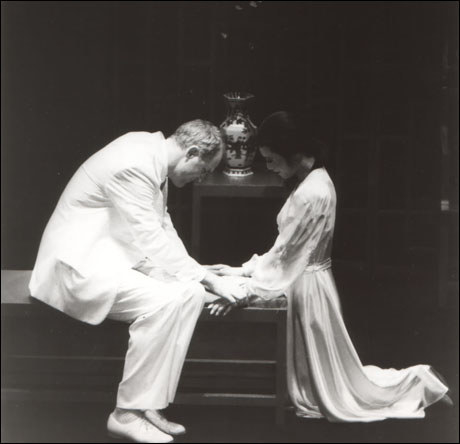

Clive Owen and Jin Ha in M. Butterfly

Matthew Murphy

When M. Butterfly premiered on Broadway in 1988, audiences were stunned to discover that the central character, Song Liling, was actually a man. Nearly 30 years later, as the revival runs at the Cort Theatre, the cat is out of the bag.

The story of M. Butterfly, which won three Tony Awards including Best Play, is now more well known than the real-life story it was based on — the affair between French diplomat Bernard Boursicot and Peking opera singer Shi Pei Pu. The culture has also progressed, and with it our language and sensitivity surrounding gender identity: The reveal of a character’s gender as a surprise twist, once a feature of M. Butterfly, now seems like a dangerously regressive relic.

David Henry Hwang

Lia Chang

That’s something playwright David Henry Hwang was well-aware of when he set about revising his play for a new production directed by Julie Taymor. In revisiting his seminal work, Hwang undertook a heavy rewrite, one in which Song’s gender is addressed early on — and the themes of toxic masculinity and Asian gender stereotypes are as clear as ever.

“Thirty years ago so much of the shock of the play was in its reveal about Song Liling, and that’s not so shocking anymore,” Hwang told BuzzFeed News. “But I do think what’s kind of shocking actually is the degree to which the play and a lot of the issues still feel current.”

The basic story of the play is the same: Rene Gallimard (Clive Owen) is working for the French Embassy in China when he meets enigmatic opera star Song Liling (Jin Ha). While he believes Song to be his “perfect woman,” Song is actually a man pretending to be a woman to spy on Gallimard. Nevertheless, the two fall in love and embark on a secret affair that conforms to Gallimard’s traditional notions of male-female relations, with Gallimard seemingly unaware of Song’s true gender identity.

Part of what makes this production of M. Butterfly seem so timely is that Hwang, along with Taymor, were able to look at it from a modern lens. But many of the big-picture ideas — chief among them the conflict between East and West, and the way archaic conceptions of gender and race play into that — have been essential to the play from the moment of its inception.

And, of course, there’s the simple matter of timing: The play is running in the midst of a cultural tipping point, in which several high-profile men have been accused of sexual harassment and assault. Hwang specifically mentioned Harvey Weinstein, but his interview with BuzzFeed News came before the allegations against Kevin Spacey and Louis C.K., among others. M. Butterfly is about a consensual relationship, but toxic masculinity is central to its identity.

“These issues of masculinity as being defined by the ability to subjugate women have become super in the consciousness with the Harvey Weinstein stuff and certainly with our president and this sense that he seems to [believe] the way that you deal with foreign policy is to take this abrasive very toxic masculine, ‘you just have to be forceful’ [approach],” Hwang said. “That’s very much an M. Butterfly kind of argument and point of view. It’s like, we’re kind of back living in an M. Butterfly world, even more so than we were two or three years ago.”

Jin Ha as Song Liling.

Matthew Murphy

Hwang is no stranger to revising earlier works, and not just his own. In 2002, he did a radical update on the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Flower Drum Song in part to combat its stereotypical depiction of Chinese-Americans. But the decision to go back to work on M. Butterfly couldn’t just be about rewriting it for a new, more socially conscious audience. “To update a play in order to conform to what’s going on in a particular moment, a contemporary moment, I don’t think that in and of itself is enough reason to rewrite a play,” Hwang said.

For Hwang, returning to M. Butterfly meant delving deep, including researching new information about the real-life couple who inspired the story. He also talked to several people with nonconforming gender identities to get better insight into the character of Song, who ultimately wants Gallimard to see him for his maleness. The character is not trans, Hwang stressed, but he recognized how Song might be differently received by a modern audience more savvy about the wide spectrum of gender identity.

John Lithgow and BD Wong in the original Broadway production of M. Butterfly.

Joan Marcus

It was in reworking the play, however, that Hwang realized how much of his original text already matched the culture we’re living in. Even as he made major changes — many of which he attributes to becoming a more mature writer — he was surprised by how on point so much of M. Butterly was. These ideas, which may have once felt radical, were now largely in tune with an ongoing national conversation.

It’s not only that the play has dovetailed with the culture at large — it’s also that M. Butterfly has impacted that culture. M. Butterfly was the first Asian-American play produced on Broadway and was hugely influential in terms of Asian-American representation in theater, simply by showing that it could be done, and profitably. “The pace felt really slow,” Hwang admitted, but he’s been encouraged by the increasing presence of Asian-American onstage and behind the scenes.

But while Hwang has championed Asian-American inclusion as a playwright and an activist, M. Butterfly’s influence can also be felt in the text itself. Hwang certainly wasn’t the first to identify the link between race, gender, and politics, but he wrote the play at a time before “intersectionality” was a term embraced by the mainstream. He also made a point of exploring the gendered stereotypes that continue to surround Asian and Asian-American people, back when these ideas weren’t widely discussed, particularly not on the platform of a Broadway stage.

M. Butterfly was undeniably ahead of its time, but Hwang believes its relevance in 2017 is directly tied to the way the country has regressed. “I’m surprised that the idea of Asian women being submissive continues to be pretty strong in the culture, particularly given the degree to which Asian countries and China in particular have become more dominant over past 30 years,” Hwang said. “The world actually has taken a bit of a step back.”

Ha and the company of M. Butterfly.

Matthew Murphy

The timing of M. Butterfly also feels oddly appropriate because of two other shows running at the same time — at the Metropolitan, Madama Butterfly, the Puccini opera referenced throughout M. Butterfly; and at the Broadway Theatre, Miss Saigon, a musical inspired by Madama Butterfly.

Hwang has a long and complicated relationship with Miss Saigon. In 1991, he helped galvanize the protests surrounding casting of white actor Jonathan Pryce as the Eurasian Engineer in the original production. Pryce went on to win a Tony for his performance, but the role has been played on Broadway by actors of Asian descent since. (Filipino actor Jon Jon Briones plays the role in the current revival.) The ripple effects of the protests are still being felt: The practice of yellowface has somehow still not ended entirely, but the instances in theater appear to be fewer and farther between, and rarely emerge without a fight.

Alistair Brammer and Eva Noblezada in the revival of Miss Saigon.

Matthew Murphy

Given the success of M. Butterfly, a play that unpacks the white savior narratives that many have criticized Madama Butterfly and Miss Saigon for perpetuating, these concurrent productions might seem like another step back. Hwang, however, has a more nuanced perspective. “If M. Butterfly‘s successful in affecting the culture, I don’t think the point is to say, we can’t do Madame Butterfly again, or we shouldn’t have a Miss Saigon,” he said.

The point is awareness, he explains. If we are living in a new culture with a better understanding of intersectionality and the harmful effects of archaic stereotypes, then we have to approach older works with a clear head and a willingness to engage. Sometimes that means rewriting, and sometimes that means recognizing cultural context and calling out the missteps. This is the work Hwang has been trying to do for the past few decades.

“If M. Butterfly‘s successful, what it allows us to do is just be aware — when we go into see a Madame Butterfly, yes, we can enjoy the music and we can enjoy the costumes and also realize there’s this kind of subliminal message and sometimes explicit message that we’re getting, which is about Western dominance, which is about Asian women being submissive, which is about white male supremacy,” Hwang said. “And I think we should be able to be conscious enough to parse that.”