When James Gunn was a kid, he kept the universe in a cardboard box in his room.

He was the oldest of six siblings — five boys, one girl — all born roughly a year apart starting in 1970. They lived in a small two-story house in the semirural St. Louis suburb of Manchester, Missouri. His dad, an attorney, was often out of town for work, and his mom was usually focused on whichever sibling was the youngest.

So Gunn began creating worlds that were just his own.

For each planet, he drew out everything he believed would matter to an alien society — the style of the houses, the shape of the pets, even the design of the plumbing — and then he placed these artifacts for his burgeoning creative universe in a box that just kept getting heavier.

“It wasn’t really storytelling,” Gunn said, almost sheepishly, at the memory. Which was easy for him to say from his office on the Disney lot in Burbank, where he had just put the finishing touches on Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, the latest — and, Gunn hoped, greatest — addition to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. On a mid-April afternoon, more grown-up artifacts surrounded him: Printed screenshots from the movie he both wrote and directed papered the walls, posters were piled on a nearby table for him to sign, and a model of his old Dodge Hellcat with Guardians action figures sprouting from the roof — a gift from Gunn’s realtor, of all people — sat beside his desk. It was hard not to notice how far Gunn had come to get to this moment.

“We grew up in our own little miniature society in which play and laughter and imagination were the highest commodities,” he explained about his family. “I just always found that ability to create these universes, whether it was a Marvel comics universe, or Tolkien’s [Middle Earth] universe, to be really fascinating.”

“His work has a ton of heart, but there’s a darkness.”

At 46, Gunn’s imagination is now in command of a creative landscape more vast and inventive than he could ever have hoped that box in his room would hold. He’s spent five years of his life working virtually nonstop on the first two Guardians movies — the first of which earned $773.3 million worldwide in 2014 and the devotion of many fans as their favorite movie ever to come out of the most successful cinematic universe in Hollywood history. With Vol. 2’s success all but assured — it’s earned $132.9 million in its initial international release so far, before opening domestically on May 5 — Gunn has already committed to writing and directing the third Guardians film.

He is also set to play a crucial role in helping the MCU grow its self-proclaimed “cosmic” universe of movies well into the 2020s — perhaps because he’s easily the director whose work feels the most distinctive, rather than the product of a well-oiled, wildly successful corporate machine. Next to Marvel Studios chief Kevin Feige, Gunn could end up as one of the most influential creative forces at the single most lucrative creative organization in filmmaking today.

But the path Gunn took to get to such a rarefied position is as unlikely as a foulmouthed, spacefaring raccoon named Rocket winning the hearts of a grateful nation. Prior to his career supernova that was Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014, Gunn had only directed two features, 2006’s Slither and 2011’s Super. Both are R-rated, extravagantly violent movies that made a meager $13.1 million between them worldwide — and they’re saturated with a pitch black comedy that doesn’t exactly scream please hire me, Disney, to make your next blockbuster movie!

“He rides that fine line of appropriateness,” Guardians star Chris Pratt gently said of the director who made him a movie star.

To wit: In between making Slither and Super, Gunn created a satirical web series for Spike.com called James Gunn’s PG Porn that is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. Then he birthed a batshit insane web short Humanzee, about a man who sends his sperm to Bratislava to create an ape-human hybrid offspring. His affinity for the freaky and the fringe stretches back to his first break in filmmaking, writing 1997’s Troma Entertainment schlockterpiece Tromeo and Juliet — in which the titular heroine deliberately transforms herself into a cow with a giant penis.

“There’s a punk element to James that is very spiky and edgy and different,” said Joss Whedon, Gunn’s friend and Marvel Studios fellow traveler. “He’s really funny, his work has a ton of heart, but there’s a darkness.”

That darkness has lingered through just about every facet of Gunn’s life, sometimes to his great distress, often at his open invitation. It has also fueled his peripatetic Hollywood career, and helped him shape the filmmaking voice that first caught Marvel’s attention.

“I was able to do exactly what I wanted, and exactly be myself, and it worked,” Gunn said of Guardians of the Galaxy. “It’s 100% my life. I’m 100% committed to it. There’s nothing else. I have a girlfriend, but I don’t have a family. I have pets. That’s it.”

He burst into laughter at the intensity of his commitment. “That’s the other thing: I’m a fucking maniac.”

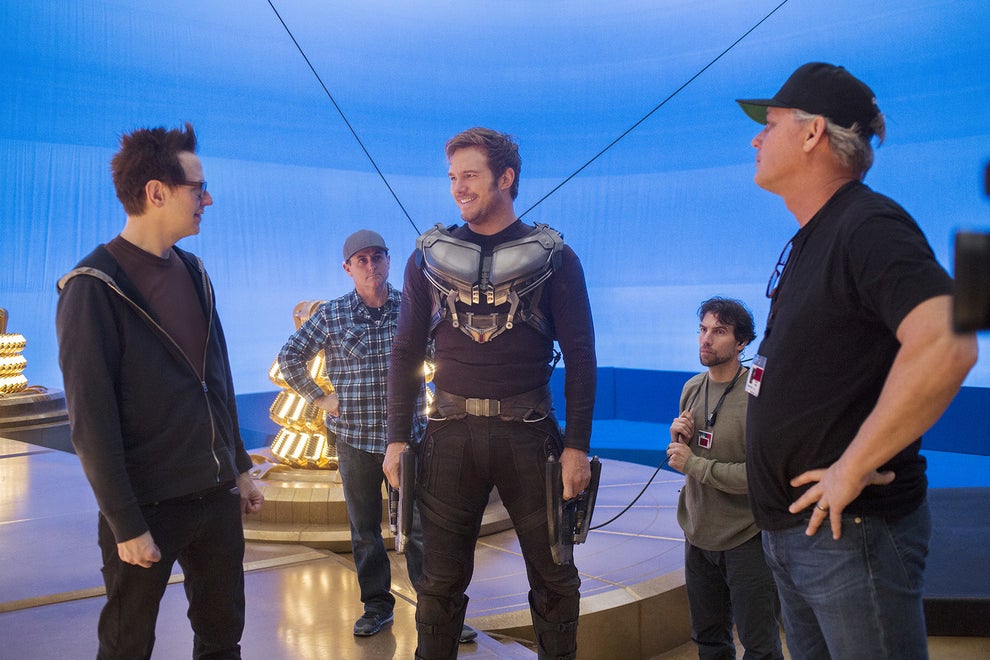

James Gunn (left) directing Chris Pratt on the set of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. Chuck Zlotnick / Marvel Studios

Having five younger siblings is ideal upbringing for a future filmmaker: You’re never without actors, and you’re never without material. “I was the kid in the neighborhood that was directing everyone else,” Gunn said. “I was director from the time I was a child.”

“Jimmy would use me as, like, a plaything, and put me in his little movies that he made,” recalled Gunn’s youngest brother Sean Gunn — who’d later go on to appear in almost all of James’ films, including both Guardians movies.

“In our family, we always had a sense that he saw himself as a sort of creative visionary,” Sean added with a laugh. “I can joke about it, but he is a creative visionary. Growing up with one is an interesting and unusual thing.” He recalled one time James and their other brother Brian put him in a box with little wooden blocks when he was young. “They taped it up, and then they were rolling it around the room,” Sean said with a smile. “He thought he was tormenting me, but I was, like, laughing and squealing with delight.”

The tight-knit, rambunctious Gunn household was also steeped in pop culture — and, for James especially, comic books. “He had boxes and boxes and boxes of comic books,” said Sean. “Tons of them. He already had a huge collection by the time I was old enough to notice it.”

Gunn’s passion for comics has certainly served his career well, but as a child, it was not something he was eager to share. “Comics were not something that as a young kid you could say you were into in Manchester, Missouri,” he said darkly. His voice, usually a couple notches louder than necessary, dropped to a murmur. “Kids did not read comic books back then. I hid it from people. … [It was] a very parochial town. Very Catholic. I think my brothers and my sister and I always had an open way of thinking about things, and that wasn’t always a valued commodity within the town I grew up.”

Starting around fifth grade, Gunn said that his school became dominated by “pretty maniacal bullies” who made his life hell. “It’s become such a thing to say that you were bullied or fucked with or whatever, but that’s what my upbringing was like,” Gunn said. “I was, like, 11 and 12 years old, and I was in a school where people were fucking and doing drugs and drinking. I guess I thought that’s what kids did.”

The catalyst for that behavior, according to Gunn, was his school’s monsignor, Russell J. Obmann. At the time, Gunn said he knew Obmann was giving young boys in his class alcohol and pornography — it was only much later that he understood the full magnitude of Obmann’s behavior. “I didn’t realize that the priest was molesting these kids, and that created this incredible society of fucked-up-ed-ness in my class,” Gunn said as he began restlessly swiveling in his chair with discomfort. “It even became a thing where, like, these notes were found by the teachers in my school of people passing notes, talking about drugs and sex. This was in fifth grade.”

“I was, like, 11 and 12 years old, and I was in a school where people were fucking and doing drugs and drinking.”

Gunn said Obmann never targeted him, and eventually the priest relocated to a different parish. (Obmann died of cancer in 2000; his St. Louis Post-Dispatch obituary notes he retired in 1993 after serving in multiple parishes, but does not mention any abuse. A representative for the St. Louis Archdioceses did not respond to a request from BuzzFeed News to comment.) Still, the experience was scarring for Gunn, in part because he said no adults in his life seemed to take it seriously.

“I love my parents very much,” Gunn said. “They’re very embarrassed by it today, but I would say, ‘Hey, mom and dad, Father Obmann is taking the kids over to the rectory and he’s showing them porn movies and giving them beer,’” he recalled. “And they’re like, ‘Aw, Jimmy.’ You know, this was back in the ’80s, before people were sensitive to that stuff. They just thought we were making up something about the monsignor at our school.”

Deeply alienated from so many of his classmates, and disillusioned by the authority figures in his life, Gunn burrowed further into his pop culture obsessions. He especially delighted in horror, particularly the classic Universal monster movies. “Every time I could, I would watch Creature from the Black Lagoon or House of Frankenstein or the original Dracula,” he said. Seeing as this is the guy who would eventually turn a lethal-if-lumbering talking tree and a green-skinned assassin into beloved movie characters, it’s clear his attraction to these films weren’t just about being afraid. “Mostly, I was into the monsters,” he said. “I think I loved the monsters. I even felt sorry for Wolfman and Dracula and all of them.”

He paused. “I think I felt like the monster.”

As a teenager, Gunn’s fixation with movie monsters shifted to more flesh-and-blood “rock-and-roll villains,” namely punk icon Johnny Rotten and shock rocker Alice Cooper. “I would go to Alice Cooper shows, and everybody would be like, ‘Hang him! Hang him!’” Gunn said with a growl. “It was always so fun!”

So much fun that Gunn yearned to experience that kind of adulation for himself. He started playing music in high school, and by his late teens and twenties, he was headlining bands and touring. But his ambition never matched how he assessed his own abilities. “I just wasn’t great at it,” he said with a sigh. “I wanted to be great at something. I thought I was a really potentially great songwriter, and I was a really great performer. But I just was not a great singer.”

Next, Gunn tried to become a novelist, enrolling at Columbia University’s graduate fiction program in the mid-’90s. To satiate his lingering desire to be onstage, he started performing monologues on the Lower East Side of Manhattan that he called “a cross between stand-up and a one-man show and a poetry slam.”

Which is to say, he needed money. A happenstance connection through his brother Matt landed Gunn an interview at Troma Entertainment. The New York-based ultra-low-budget film company existed on the outskirts of the filmmaking galaxy, first rocketing into cult cinema infamy with its 1984 exploitation horror hit The Toxic Avenger.

“They’re trashy, mutant, sex and violence movies,” Gunn said of Troma’s reputation. “I think I was hoping that I was going to get a job working on special effects or something in making blood.”

Instead, after their first interview, Troma chief Lloyd Kaufman offered Gunn the opportunity to write Tromeo and Juliet — a trashy, mutant, sex and violence adaptation of Shakespeare’s perennial love story — for $150.

Director Lloyd Kaufman (center, left) and Sean Gunn (center, right) on the set of Tromeo and Juliet. Troma / REX / Shutterstock

“I remember lying in bed in my little shitty apartment on the Upper West Side, and I was like, Holy shit, my name could be on a movie,” said Gunn. “Forever. That freaked me out.” In an instant, Gunn’s childhood hobby of making movies had transformed into an abiding, lifelong passion. “I have to say, I feel a weird sort of calling in filmmaking that I didn’t feel with other things,” he said. “I feel like there are things in life you want to do, and then things you are called to do, and hopefully you can allow yourself to want to do whatever you’re called to do.”

The experience working on Tromeo and Juliet gave Gunn a crash course in what would become a crucial skill for joining the MCU: learning how to weave his own creative impulses into a vivid, and rigid, cinematic style. “The genre was Troma,” said Gunn. “But within that, there was a bunch of stuff that was this mix of really, really dark stuff and light stuff, slapstick almost, at the same time. That was the stuff for me.” For example, Gunn said it was his idea to allow the two star-crossed lovers in the movie to survive, learn that they were full-blooded siblings, and still decide to run off together and have a family of deformed children. (Gunn also recast Friar Laurence as a pedophile priest.)

As exploitation movies go, Tromeo and Juliet was a genuine hit. The New York Times even raved that the film was “deliriously grossed-out” and “goofily exhilarating.” With his buzzy cult success, Gunn decided to move to Los Angeles to start his career in the movie business.

But when he arrived, he said, “Nobody gave a shit.”

It was the late ’90s, and comic book movies were still living down the kitschy humiliation of Batman & Robin. But that didn’t keep Gunn from writing a comedy called The Specials, which followed a second-rate superhero team through the petty tribulations of a regular day. His irreverent, human-scaled approach stood out as a bracingly fresh approach to the genre, and the script attracted a solid cast, including Rob Lowe, Thomas Haden Church, Paget Brewster, and Judy Greer. (Gunn also secured supporting roles for himself and his brother Sean.)

The night before the film began production, however, Gunn was filled with dread. “I was lying in bed thinking, This is not going to go well,” he said. “I could tell by how it was being made that it was just not going to be good.”

From left: Rob Lowe, Thomas Hayden Church, Judy Greer, and James Gunn in 2000’s The Specials.

His instincts proved accurate by at least one brutal measure: According to Box Office Mojo, The Specials opened on Sept. 22, 2000, in only two theaters, and grossed a grand total of $13,276.

That might have been it for Gunn’s career, but the movie managed to capture a rarefied fanbase of industry professionals who saw an invigorating new voice in genre filmmaking. “I think that movie is vastly important,” said Whedon. “Nobody had done a modern version of deconstructing superheroes so perfectly. It informed how we write superheroes as much the most ponderous, ‘I have the weight of the world on my shoulders’ kind of thing. I make everybody I know watch it.” (Whedon said his enthusiasm for The Specials, in fact, was what first led Marvel to consider Gunn for Guardians.)

“I don’t think through anything I do, and it’s landed me in huge amounts of trouble.”

After working on a few projects that ultimately didn’t get made — like a half-hour comedy TV pilot with Whedon called Cheap Shots, about a low-budget horror movie company — Gunn was hired to adapt one of his favorite TV shows as a kid, Scooby-Doo, into a live-action feature. The movie that ultimately opened in 2002 was a PG-rated family-friendly comedy, but that’s not the film Gunn set out to write. “I mean, I wanted Wes Craven to direct it,” Gunn said with an impish grin. “I wanted it to be funny and crazy and then scary as fuck.”

It was almost crazy as fuck: When the MPAA first screened the finished film, according to Gunn, they balked at a scene in which a voodoo priest “said something that sounded like, ‘I don’t eat pussy’ or something like that,” said Gunn. “That was the insinuation.” It was easy enough to cut out, but when the studio realized they wanted a kids movie instead, Gunn said they also lost a scene in which Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Daphne and Linda Cardellini’s Velma kissed. The producers even used CGI, he said, to erase the actors’ cleavage.

The toned-down film was a hit, and Gunn’s next two screenwriting gigs — a modern remake of the zombie classic Dawn of the Dead, and Scooby-Doo 2: Monsters Unleashed — both opened at number one on back-to-back weekends in March 2004. Gunn was able to parlay his newfound heat in the industry into finally securing his directorial debut, the original horror comedy Slither.

Actors Brenda James, Nathon Fillion, Don Thompson, and Jennifer Copping in 2006’s Slither. Moviestore /REX / Shutterstock

Similar to the wild swings in tone he attempted in Tromeo and Juliet, Slither seesaws from grisly horror to genuine pathos to (literal) gut-busting comedy, occasionally within the same scene. The movie follows mild-mannered high school teacher Starla (Elizabeth Banks) whose jerk of a husband (Guardians’ Michael Rooker) has been taken over by an alien space slug, and critics adored it — Variety called the movie “ingeniously twisted.” But Slither belly flopped when it opened in March 2006. “In retrospect, it was remarkably deaf in terms of what was commercial,” Gunn said. “I remember realizing that there had never been a horror comedy that had made money. I was like, What have I spent the last year and a half of my life doing?!“

He shrugged when asked what drove him to make Slither in the first place. “I’m not that complicated — I just had an idea for a story and started writing it,” he said. “I don’t think through anything I do. I just do it, and it’s oftentimes landed me in huge amounts of trouble.”

A few minutes later, Gunn interrupted himself, and returned to the question. “Looking back at Slither, it’s about my marriage falling apart, in a lot of ways,” he concluded. “At the time when I was writing it, I thought it was about a dissolving marriage, but I didn’t think my marriage was actually dissolving. I didn’t totally realize that.”

That marriage, which lasted from 2000 until they officially separated in 2007, was to The Office star Jenna Fischer — and if you’re looking to spend an hour of your life feeling a rising sense of discomfort, try watching LolliLove, the 2004 short film starring Gunn and Fischer as heightened versions of themselves. Over the course of the film, as “James” and “Jenna” try to launch a ludicrously misguided charity to give lollipops to the homeless, their sniping — due largely to James’s thoughtless, selfish behavior — becomes poisonous. Fischer directed the largely improvised film mockumentary-style, and knowing that the two would ultimately divorce in real life only makes their bickering that much more awkward to sit through. No more so than for Gunn.

“I did see it recently, for the first time in a long time,” he said, his face transforming into a perfect 😬. “I showed it to my girlfriend. I forgot that there’s was so much stuff in there with my ex, and I was like, yeesh.”

Gunn and Jenna Fischer at the 2002 premiere of Scooby-Doo (top) and in 2004’s Lollilove. Frederick M. Brown / Getty Images, Troma Films / Courtesy Everett Collection

Gunn stressed that he and Fischer, who remarried in 2010, have remained good friends. “We talk all the time,” he said. “We spend Christmas Eve together almost every year. We’re not the typical divorced people. It’s like she graduated into becoming a sister to me.” (Fischer’s publicist said she was on vacation and unable to comment for this story.)

Gunn was equally clear that he harbored zero regret over making LolliLove. “We’re using the worst parts of ourselves and making them characters, because it was funny,” he said. “One of the most fun times I’ve ever had at a screening is when we screened LolliLove at the St. Louis Film Festival, and at the end of the movie, ‘James,’ who’s a germaphobe, gets spit on. The audience [was] applauding and howling, because I’m the ultimate villain!” Gunn burst into laughter, clapping at the thought of his own “hang him! hang him!” Alice Cooper moment. “It just felt really good.”

Putting a loathsome version of himself on display for public consumption has been almost a compulsion for Gunn throughout his career. He plays “James Gunn” in his 2009 web short Humanzee, in which he urinates on his chimp-human mutant son (played in heavy makeup by his brother Sean). And his first — and, to date, only — published novel, 2000’s The Toy Collector, follows a hospital orderly and alcoholic named “James Gunn” who sells prescription pills to fund his private stockpile of childhood toys. Gunn did work as a hospital orderly, and he dropped out of Loyola Marymount’s undergraduate film school and moved back home to Missouri because, he said, “I was doing a lot of drinking and drugs, and sort of just bottomed out.”

So is The Toy Collector autobiographical?

“I mean, there’s things in it that are true, but there’s also a lot of things in it that are untrue,” he said, his voice once again dropping several decibels. “Or at least didn’t happen. So, not completely. I don’t know if it is that I am or was a dick, or if that was something I put forward because I was uncomfortable with who I really am.” He paused to scratch his temple, and the tone of his voice pivoted into upspeak. “I’m uncomfortable with vulnerability and I’d rather be a dick than be vulnerable?”

In a way, Gunn attempted to answer that question with his follow-up feature, Super, which pushes the comic-book-heroes-as-real-people conceit of The Specials to its furthest edge: When Frank (Rainn Wilson) falls into despair after his newly sober wife Sarah (Liv Tyler) leaves him for a scuzzy drug dealer (Kevin Bacon), a divine vision guides him to become a costumed vigilante called the Crimson Bolt, who bludgeons would-be evildoers with a wrench. Frank, however, isn’t particularly discerning about what constitutes “evil.” In one standout scene, he splits a man’s skull open after he cuts in line at a movie theater. The shocking sight of the blood spurting from his head elicits a kind of stunned laughter, but it also underlines how quickly superheroes turn to the kind of brute force that would in truth be horrifying to behold.

Super is also in many ways the most personal film Gunn has ever made: Starting when he was in high school, and lasting well into his twenties, he said he experienced “full-on, knock me down, total visions.”

“It’s a dangerous thing to talk about what that movie is about to me, because I think it could be taken in the wrong way,” Gunn said.

In Super, Frank’s central vision involves the giant hand of God reaching into his bedroom and touching his exposed brain while disembodied, seemingly alien tentacles hold him to his bed. “That’s an interpretation, but the finger of God, yeah, that’s totally real to me,” Gunn said. “An ex-girlfriend thought that I probably had frontal lobe epilepsy. … Part of me thinks of it as strictly some sort of biochemical thing, then part of me thinks [it’s] outside of that, and then part of me thinks of some combination that we just don’t understand. So, yes, Super is very personal to me because of that. And it’s a hard thing to, you know, discuss with people.”

When Super opened in 2011, it had the misfortune of following the much more crowd-pleasing movie Kick-Ass — which also featured ultraviolent, costumed vigilantes — and its critical and commercial reception suffered as a result. “Super was incredibly disorienting to people,” Gunn said with a wince. “I frankly felt misunderstood.”

So much so that he began to question his place in Hollywood. “I didn’t know what the fuck I was going to do,” he said. “I always thought I was going to be a big director. I just always assumed that’s where I was headed. And then all of a sudden, it didn’t seem like that was the case.”

“Nobody’s going to give me a Marvel movie.”

Super came after Gunn had abandoned an earlier attempt to make an idiosyncratic spin on mainstream sci-fi, a Ben Stiller studio comedy called Pets, about a guy who is abducted by aliens and placed in a giant hamster-like maze with other domesticated humans. He loved the concept, but he grew weary of the barrage of notes he was getting. “It kept getting milkier and milkier and milkier,” Gunn said of Pets, with a deep sigh. “I thought I was bringing my unique voice to this project, but instead it seemed like any A-list director in Hollywood would make the exact same movie. Why would I deal with something where I feel like I’m not of use because it’s just becoming a vanilla thing?”

It felt like there was no place for Gunn in modern Hollywood, and his natural creative instincts were keeping him perpetually stuck on the perimeter of the industry. So he called up his agent and manager, and told them he was done as a film director. “I just was at a place where I didn’t want to do things that were just disappearing into nowhere,” he said. “I wanted to be a part of the conversation. And nobody’s going to give me a Marvel movie.”

A week or so later, that’s exactly what happened.

Marvel had been trying for years to figure out how to transform Guardians of the Galaxy, one of its most obscure comic book titles, into a viable movie franchise. Since 2009, screenwriter Nicole Perlman had been developing the title as part of the studio’s writing fellows program, and her progress left the company bullish enough to make Guardians its first new franchise launch after The Avengers. If successful, the film’s space opera trappings could radically expand what audiences would consider to be a “Marvel” movie. By 2012, however, the script still wasn’t where it needed to be to share a creative universe with Iron Man, Captain America, and Black Widow.

“The early drafts were trying very hard to be Star Wars,” said Whedon, who was serving as a kind of an executive creative consultant for the entire MCU, along with directing The Avengers and Avengers: Age of Ultron. “And there was a lot of stuff that we worked on to drain it of its importance.” When Whedon learned Marvel was considering Gunn for the job, the project finally began to click into place for him. “I was definitely the skeptic going, Uh, so, raccoon?” he said. “And James came in and was like, raccoon!“

In truth, Gunn almost didn’t take the meeting at all because he didn’t want to drive to Marvel’s offices in Manhattan Beach, he believed Marvel’s interest in him to be pro forma, and his indifferent-at-best opinion of the sporadically released Guardians of the Galaxy comics left him less-than-thrilled by the idea of a Guardians movie. Gunn took the meeting anyway — turning it down would have been the most insane. But it wasn’t until the drive back home that Gunn began to think about Rocket, and what it would actually mean for him to be modified into a two-legged talking raccoon. His imagination began to click into gear. Suddenly, he saw “what I could make those characters,” he said.

Michael Rooker as Yondu (left) and Rocket in 2017’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. Marvel Studios

“He sent over maybe a 20-page document, and on the cover of it was a picture of a vintage Sony Walkman,” recalled Marvel Studios chief Kevin Feige of Gunn’s initial treatment. “Before I even turned the page to actually read any of the text, I thought, ‘This is unbelievably perfect.’”

The Guardians were, in Whedon’s words, “a footnote” within the Marvel comics well outside the more familiar territory of the Avengers. “That’s a perfect playground for James, because they don’t have to worry about, Well, that seems wrong for Thor,” Whedon continued. “James is not going to bother to make something that is just punching in a clock or fulfilling an agenda. He would only ever make a James Gunn movie. And luckily, what he wanted to do is exactly what Marvel wished he would do. So it’s a perfect confluence.”

The puckish irreverence that had largely kept Gunn on the periphery of Hollywood matched the material Marvel had handed him. “The odd thing is even though some of his stuff is really dark and twisted — I mean, you’ve seen Humanzee — honestly the thing that is most him is Guardians,” said Sean Gunn.

“Everything about his life and his experiences, he found a way to pour into that movie,” agreed Feige.

In Gunn’s hands, Peter Quill (Pratt) transformed from a half-alien NASA astronaut into a rogue with a soft spot for ’70s and ’80s rock, a cheeky disregard for the rules, and unresolved issues with his less-than-perfect father figure, Yondu (Rooker) — who mutated from a noble archer to a disreputable space pirate. Drax the Destroyer (Dave Bautista), originally a grim brute, was now hilariously literal-minded, speaking bluntly, and oblivious to the consequences. The villain, Ronan the Accuser (Lee Pace), adjusted from a kind of bad, sometimes good, alien judge into an unrelenting and abusive religious fanatic. Gunn even slipped in a cameo for the alien slugs from Slither.

Gunn directs his brother Sean on the set of 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy. Jay Maidment / Marvel Studios

And although Rocket — voiced by Bradley Cooper, and played on set by Sean Gunn — largely kept his background from the comics as the perpetually underestimated engineering genius, Gunn imbued the character’s wickedly mean sense of humor with the notion that he didn’t care if people thought he was a raving asshole, and actually kind of preferred it that way. One could even say he made Rocket into the the latest, raccoon-iest version of “James Gunn.”

“[He’s] 100% the most personal character I’ve ever written,” Gunn said softly, clasping his hands against his chest, as if holding the character closer to him. “He’s the most me. I can’t even really talk about it much. Definitely. Definitely. He’s me.”

Gunn explored his connection with Rocket even further in Guardians Vol. 2, as the furry misanthrope slowly begins to appreciate the value of keeping genuine, emotional bonds with others. The sense that the frayed, familial connection the Guardians characters all share with one another are more vital than they’re willing to acknowledge infuses the entire film with a surprising well of deep feeling. “I was moved to tears when he pitched me the idea before he’d even written the script,” Pratt said.

It also happened to mirror exactly how working on this massive Hollywood franchise has affected its director.

“I protect myself by writing scenes where people shoot people in the face,” Gunn said, chuckling. “And if I have to think around shooting someone in the face, it’s harder, but I think it’s more rewarding for me.” He cleared his throat. “I felt like Guardians forced me into a much deeper way of thinking about, you know, my relationship to people, I suppose. I was a very nasty guy on Twitter. It was a lot fucking edgy, in-your-face, dirty stuff. I suddenly was working for Marvel and Disney, and that didn’t seem like something I could do anymore. I thought that that would be a hindrance on my life. But the truth was it was a big, huge opening for me. I realized, a lot of that stuff is a way that I push away people. When I was forced into being this” — he moved his hand over his chest — “I felt more fully myself.”

And what’s “this”?

“Sensitive, I guess?” he said. “Positive. I mean, I really do love people. And by not having jokes to make about whatever was that offensive topic of the week, that forced me into just being who I really was, which was a pretty positive person. It felt like a relief.”

Hiring filmmakers who’ve never made a giant blockbuster movie before has kind of been Marvel Studios’ thing ever since they handed Jon Favreau the reins to 2008’s Iron Man. But until Gunn, none of them had previously lived quite so far on the outré periphery of Hollywood — or had subsequently crafted giant blockbuster movies that felt so intimately connected to the director behind them.

“The funniest thing to me about James’s success right now is that he’s proving himself to be as much of a genius as he always told us that he was,” Sean Gunn said, breaking into a sustained peal of laughter. “Which I think is funny, but, you know, it’s vindication, right? There’s probably just a big monkey off his back in terms of feeling like there’s some level of greatness that he’s destined for that he’s chasing after.”

“He’s proving himself to be as much of a genius as he always told us that he was.”

That success, of course, has come within the confines of Marvel’s well-appointed, walled-off playground — and James Gunn is in no rush to leave it. He’s an executive producer on 2018’s Avengers: Infinity War, the first time the Guardians characters will engage with the larger MCU, and after writing and directing Vol. 3, Gunn will help the studio make more movies within its “cosmic” realm.

“[It’s] basically me saying to Kevin, ‘OK, we’re going to do Guardians Vol. 3, and then I think those characters should have his or her own movie, and then this character here, and then we should bring this person in,’” said Gunn. “I think that they just trust me in terms of my vision of the more space opera aspects of Marvel. … I love the freedom to be able to create that fully. That doesn’t mean I never want to make an R-rated movie again, or make even a small movie. But right now, I feel really creatively fulfilled doing this.”

Which isn’t to say that Gunn suddenly thinks he’s one of the popular kids now — but that’s just as well. “I do feel like an outcast, someone who didn’t feel like he belonged his entire life,” Gunn said. “With the Guardians, that’s who they speak to. To me, that’s the best thing entertainment can do. That’s why I loved Alice Cooper and Johnny Rotten. Because I was a fucking lonely little kid living in Manchester, Missouri, surrounded by a bunch of messed up people. And I’d listen to an Alice Cooper record, and I’d go, ‘Wow, this guy is as weird as I am, and he’s, like, far away.’ But he made me feel less alone.” ●