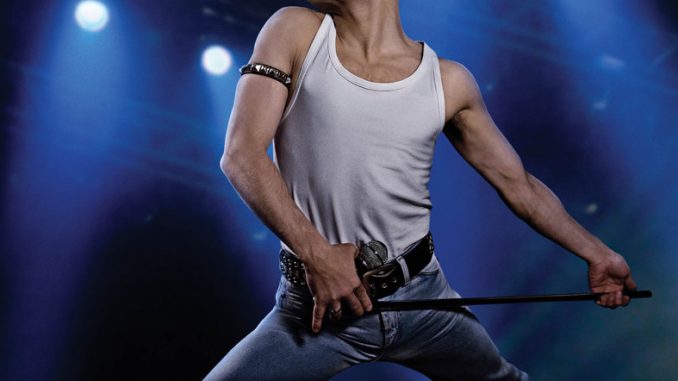

Rami Malek as Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody.

Celebrity biopics are, almost by definition, formulaic narratives depicting some combination of rise, fall, and redemption. But they work best when they are able to move beyond the conventional wisdom about an artist or public figure, finding a previously unexplored slice of their life that illuminates something new about them. And in some ways, the subgenre of movies about famous queer figures who were never out during their careers can more easily circumvent the cookie-cutter biopic problem, because the very fact of depicting their star’s sexuality gives them a headline-making angle.

When the news broke that a biopic about Freddie Mercury and the British rock band Queen was in the works, some critics expressed concern about how Mercury would be represented. Sacha Baron Cohen, who became attached to play Mercury in an earlier version of the project in 2010, dropped out by 2013 because he felt the film would fail to depict the “nitty gritty” underside of Mercury’s life, like his drug parties. The film’s original director, Bryan Singer, was fired in the midst of the production in December last year and replaced by Dexter Fletcher, though Singer retained sole directing credit. Then, after the release of the promotional trailer for the film earlier this year, emphasizing Mercury’s relationship with a girlfriend, Mary Austin, critics immediately accused the film of straight-washing.

Mercury, the band’s frontman, never came out to the general public or labeled himself in an interview. But we now know that his last major romantic relationship was with a man, and he was open with those in his inner circle about his relationships with men. His death from AIDS complications in 1991, when the illness still carried a scandalous connotation of gay male promiscuity, made him one of those celebrities, like Rock Hudson or Liberace, whose image became in some ways defined by queer tragedy.

The film that will premiere on November 2 after 10-plus years in production limbo, Bohemian Rhapsody, isn’t necessarily a straight-washing of Mercury’s private life, nor does it shy away from his drug use. But it ultimately sells a moralistic, sanitized version of his life and music, rendered “respectable” for mainstream audiences — both because of what the film emphasizes and what it leaves out. The movie doesn’t deny his sexuality, but it also doesn’t explore the nuances of Mercury’s life or art as a queer man.

In a telling early scene, as the band is in the process of securing their first major record deal, Mercury explains the group’s unique appeal to a record executive as that of misfits singing for misfits. But it was actually Mercury, a queer man and immigrant, who was the outsider, both within the band and outside of it — and the film would have been stronger if it had explored those tensions. Instead, this latest biopic about a celebrity who wasn’t public about his sexuality during the height of his fame ultimately serves as a cautionary tale about how difficult it remains for mainstream films to do justice to queer lives and legacies.

In order to understand the limitations of Bohemian Rhapsody, it’s important to understand its genesis. Former Queen manager Jim Beach is one of the producers, and bandmates Brian May and Roger Taylor were creative consultants. They apparently had approval over the script at some point and even helped decide who would play Mercury and direct the film.

As Sacha Baron Cohen explained after he dropped out of the project, the bandmates had their own self-serving ideas about how the project should work. “A member of the band, I won’t say who, he said, ‘This is such a great movie because it’s got such an amazing thing that happens in the middle of the movie,’” Baron Cohen recalled. “I go, ‘What happens in the middle of the movie?’ He goes, ‘Freddie dies.’”

Baron Cohen realized the bandmates wanted the second part of the film to focus on Queen’s journey after Mercury. He presciently told them, “Listen, not one person is going to see a movie where the lead character dies from AIDS and then you see how the band carries on.’” The resulting film — over which guitarist Brian May and fellow band members claim they ultimately had little control — certainly does center on Mercury, but it circumscribes his life entirely within the band’s journey, and flattens it in the process.

The movie doesn’t deny his sexuality, but it also doesn’t explore the nuances of Mercury’s life or art as a queer man.

The film starts and ends with the band’s famous Live Aid concert from 1985. What we see of Mercury’s life begins as the band’s life begins: Mercury impresses two of his bandmates in an impromptu audition after their original singer quits. What we don’t see is how he actually developed his musical skills, or any of his influences. From the background in design that helped Mercury create his stage persona, to his selection of the campy band name — which the other bandmates initially disliked — his perspective helped shape the unique, gender-bending style that gave the band massive worldwide success. But given how much the story leaves out about his early life and his own development outside of his family or the band (often referred to as his second family), it’s difficult to see or understand his perspective.

The film presents the selection of his stage name, Freddie Mercury, not in terms of what it means to him, but in terms of how his father feels about it — as a rejection of his family name and heritage. (Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara, in Zanzibar, in what is now Tanzania; the movie frequently depicts him chafing under the conservatism of his immigrant parents.) And while we see a quick scene of Mercury creating the Queen logo at one point, we aren’t given any sense of what the name meant to him or why he chose it, other than it’s “outrageous.”

The band’s rising success is depicted in a series of concert montages, but a more specific focus is devoted to Queen’s recording of “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Mercury wrote the song, and many, including the band’s former manager, have speculated that it was about his sexual identity. Whatever the lyrics allude to, the song was emblematic of Mercury’s voraciously genre-crossing genius, and a spectacularly queer crossing of high and low, opera and rock.

But in the film, despite almost laughably generic images of Mercury being inspired by a natural landscape, we never get to see how the song emerged through his experiences or what it meant to him. Instead, there are jokes about how one of the bandmates sounds castrated because of how high Mercury makes him sing. (During the last concert scene, when Mercury sings the song, he sends a kiss to his mom during the famous “mama” line, another reminder of how everything about the development of his artistic identity in the film is reduced to the context of the band or his family.)

Queerness isn’t just about the intricacies of a private life; it can also be about a certain sensibility or style, especially when it comes to artistic creation. Mercury’s music and persona were revolutionary in part because they evoked a queer aesthetic, which the film itself suggests his bandmates weren’t always comfortable with. For example, they balk at wading into disco in the ’70s, which was often dismissed as a gay genre at the time, especially in rock circles; the bandmates claim disco is just “not Queen,” but we aren’t given any idea of what disco meant to Mercury, who is briefly shown sashaying in gay clubs.

As Mercury finds himself in the film, he adopts a gay male style of handlebar mustache and jeans that became known as a macho clone look in the ’80s. The band members, consequently, make disparaging comments to him, like “we’re Queen, not the Village People.” That particular remark is depicted as a throwaway joke, rather than being examined for what it might reveal about Mercury’s relationship with his straight bandmates, or what it meant to him to claim that style in public during such a deeply anti-gay moment. It’s one thing to be flamboyantly gender-bending in the glam rock mode, and another thing to adopt a style that was specific to the gay subculture.

Mercury’s music and persona were revolutionary in part because they evoked a queer aesthetic, which the film itself suggests his bandmates weren’t always comfortable with.

In contrast, the film devotes a lot of time to Mercury’s relationship with a girlfriend, Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton). There is nothing wrong with emphasizing that relationship, which meant a great deal to Mercury in real life. But that emphasis becomes problematic when compared to the limited way his relationships with men are portrayed.

Mercury is first shown cruising for a man to hook up with at a truck stop during an early tour as he talks to Mary on the phone, presenting his exploration in terms of what it means for the suffering girlfriend. He is then seemingly initiated into gay sexuality through the predatory Paul Prenter, a former manager who gropes him and forcibly kisses him. As written in the movie, Prenter is an almost mustache-twirling villain, who encourages Mercury’s descent into drugs and clubs. (The film presents Mercury as someone who’s discovering himself through his sexuality as an adult, but a biographer points out that even his schoolmates knew he was “homosexual” as a child.)

The movie presents Mercury’s drug use and sexuality as intertwined, and frames both moralistically — through Prenter’s bad influence — as if Mercury didn’t find pleasure and even sources of artistic inspiration through his queer experiences and community. In contrast, for instance, girlfriend Mary is shown encouraging his interest in androgynous fashion early on.

Mercury leaving the band for solo projects is depicted as a big moment, but presented as a selfish action caused by Prenter’s influence — rather than, for example, frustration with his straight bandmates, or because he thought of himself as a serious artist with his own things to say. Mercury is ultimately “rescued” from this life of drugs, sex, debauchery and Prenter’s influence, and reunited with the band, through girlfriend Mary toward the end of the film.

Rami Malek, the straight actor who plays Mercury, defended the movie’s decision not to focus on what he called the “darker” aspects of Mercury’s life. “To make a movie about some aspects of his life that were darker and seedier than the ones I want to celebrate is not a worthwhile expenditure of my time, or an audience’s as far as I am concerned.” But there is nothing inherently dark about Mercury’s story, and no need to “protect” representations of queer men from drugs and sexuality, or to depict those men as angels or victims (seduced by other bad gay villains).

The straight director of a recent documentary about Alexander McQueen took a similarly sanctimonious view regarding the designer’s experiences exploring drugs and sexuality, and his diagnosis as HIV-positive. “You know, there are a lot of dark elements in [McQueen’s] life,” he explained. “We wanted to mention it and we didn’t want to whitewash it, but we never wanted to dwell in what we would have felt would be vulgar.”

That film also covers McQueen’s explorations with drugs and sex in a surface way without exploring them as a source of discovery, and it also glosses over what his HIV diagnosis meant to him. Both McQueen and Bohemian Rhapsody seem to be stuck in a moment when the AIDS crisis was shallowly understood as a tragedy that grew out of gay men partaking in a “seedy” lifestyle, rather than the result of anti-gay prejudice and governmental negligence in the face of a public health crisis.

Mercury’s last partner, Jim Hutton, is slotted in through two scenes in the movie — lecturing Mercury during his drugs-and-clubs period, and then showing up at his front door right before the final Live Aid concert — in what comes across as an attempt to redeem Mercury’s queerness with a “respectable” partner. When Mercury is diagnosed with HIV near the end of Bohemian Rhapsody, he accepts his fate with his usual archness, telling the band he doesn’t want to be a poster boy or cautionary tale for AIDS. Yet as he walks out of the hospital after his diagnosis, a white light engulfs him, as if he’s now become some kind of martyred angel, ready for what is portrayed as his climactic 1985 Live Aid concert with Queen. (His diagnosis actually came after that show, but it is all backdated to fit into the band’s story.)

Whether or not this was a peak moment in Mercury’s own life, the film makes it a moment of faux resolution. He subtly comes out to his parents right before the concert, even though, according to his mother, he never did in real life. It’s almost as if the film is afraid of making audiences uncomfortable with the reality of queer pain, and as if, from beginning to end, Mercury’s life was most meaningful in terms of what he meant to his family and to the band, rather than what he meant to himself.

There’s some interesting overlap between Mercury and Liberace, the subject of 2013’s Steven Soderbergh biopic Behind the Candelabra. Both were flamboyant musical showmen who disrupted conventional ideas about masculinity. And like Liberace, speculation about Mercury’s sexuality and his death from AIDS complications led to a big tabloid presence and afterlife, all of it adding to his myth.

Soderbergh’s biopic was a compelling take both on the complexities of Liberace’s appeal — selling a melange of wholesome camp to Middle America — and an interesting look behind the scenes of his life. Soderbergh had to make the movie with HBO, as opposed to the bigger theatrical distributors he’d worked with in the past, because, as he put it, “Nobody would do it. They said it was too gay.”

That film was, not incidentally, based on Liberace’s male lover’s memoir. The question of whose perspective should inform a life story is always important, but it is especially so with queer icons. Mercury’s ex-partner Prenter is portrayed in the film as a villainous sellout, because they had a falling-out and he sold his former lover’s stories to the tabloids. In contrast, there’s no suggestion that his bandmates might have had their own biased perspective and commercial agenda. Mercury’s bandmates have admitted they didn’t know much about his private life, and other reviews have noted how Rhapsody almost comes off as an attempt by the band to settle a score with Mercury, because he wrote most of the band’s hits and, since his death, has become the most famous member.

In an interview, actor Rami Malek highlighted the universality of Mercury’s fame, suggesting that thinking of him as a “gay icon” was reductive. “He didn’t allow himself to be categorized or defined, put in any box — he was a revolutionary.” This is the kind of comment that filmmakers or Hollywood executives often make to imply that telling a story from a specifically queer perspective is somehow reductive or provincial. But artists become revolutionaries because they create something that comes from a very particular place.

In an interview with the BBC, bandmate Brian May played up the film’s tortuous 10-year production schedule as a sign of its seriousness: “Movies that mean anything very often go through a very difficult gestation period and this is probably no exception.” But in its attempt to tell Mercury’s very particular, and specifically queer, story through his straight bandmates’ eyes and the most normative conventions, Bohemian Rhapsody ends up saying almost nothing at all.