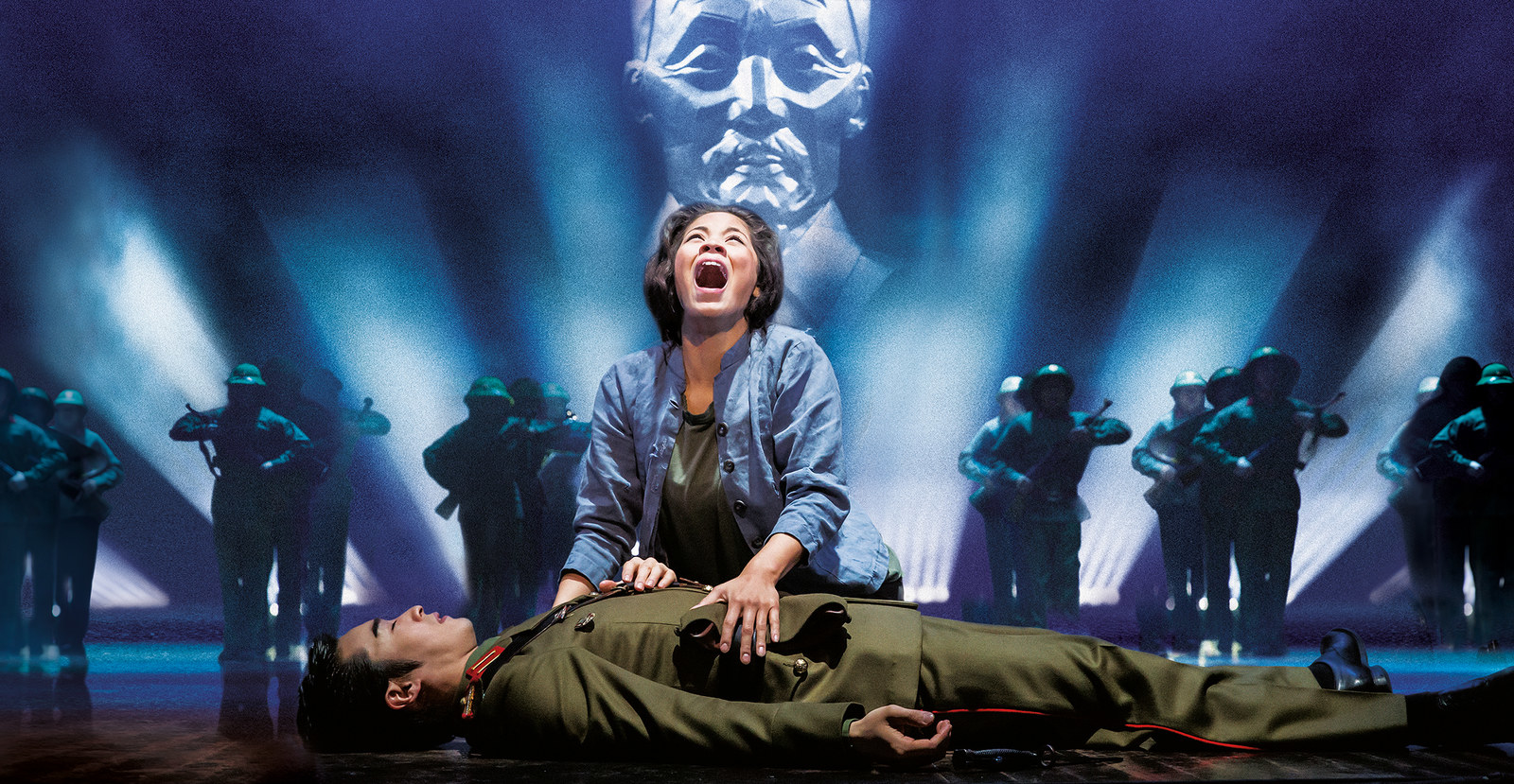

Eva Noblezada as Kim in the London production of Miss Saigon. Matthew Murphy

When Miss Saigon opened on Broadway in 1991 amid protests against its yellowface casting and characterization of Vietnamese people, Eva Noblezada wasn’t born yet. The star of the Miss Saigon revival, which opened March 23 at the Broadway Theatre, brings a fresh perspective to a show with a complicated history — even as Miss Saigon itself continues to evolve past its contentious beginnings.

The controversy over Miss Saigon — which began with the casting of Jonathan Pryce, a white actor, as the French-Vietnamese engineer, in 1989 — has never really gone away: Protests over the show have followed it throughout various productions over the past 28 years. But the noise has certainly lessened, in part because the show has made significant efforts to correct past mistakes. Following the uproar surrounding Pryce’s casting and the prosthetics and makeup he wore, the part has been played exclusively by actors of Asian descent. (In the current Broadway revival, Filipino actor Jon Jon Briones reprises his role from the London production.) The lyrics, too, have been revised, in an effort to add complexity to the show’s portrayal of Vietnam and its people.

For 21-year-old Noblezada, Miss Saigon’s controversial past does not factor into her performance. She deliberately approached the show with a certain remove: When she first took on the role in London in 2014, her research focused on Vietnam and the Vietnam War and not on Miss Saigon itself. “I didn’t really do any research on the show before we started,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I’m a person who needs a blank page. I needed to start from scratch and get my own inspiration.”

Even the plot and the score of Miss Saigon were largely new to Noblezada before she was cast as Kim, the innocent but headstrong young woman who gets her heart trampled over the course of nearly three hours. Based on the Puccini opera Madame Butterfly, the show depicts the ill-fated romance between Kim and Chris, an American GI stationed in Saigon during the Vietnam War. Miss Saigon is remembered for its soaring ballads — Claude-Michel Schönberg wrote the music, with lyrics by Alain Boublil and Richard Maltby Jr. — and its grandeur, including a memorable Act 2 cameo by a helicopter.

That Noblezada had only a passing knowledge of Miss Saigon prior to starring in it isn’t all that surprising when you consider her story: She was 17 when she was discovered as a high school student at the National High School Musical Theatre Awards, better known as the Jimmy Awards, in New York City. Though Noblezada didn’t win, she caught the attention of casting agent Tara Rubin, who encouraged her to audition for an upcoming production of Miss Saigon.

Being plucked off the stage during a high school competition is the kind of fantasy scenario that most young theater aspirers can only dream of. Noblezada could barely process it. “I think it didn’t hit me until I got home that, OK, that happened, and now I’m actually doing an audition for Miss Saigon,” she said. “It happened so quickly.”

After a successful audition and a couple of callbacks, Noblezada suddenly had an offer to play Kim in the London revival of Miss Saigon. She’d have to leave home in North Carolina for the first time and move to another country, making a quick transition from high school productions to a leading role on the prestigious West End. The prospect was equal parts thrilling and daunting — but Noblezada never considered saying no. “I was wanting to move out and do my own thing when I was 15,” she admitted.

Suddenly immersed in the world of professional theater, Noblezada found that in some ways, her youth worked to her advantage. Kim is 17 when Miss Saigon begins, orphaned and forced to work as a bargirl in a seedy bar and brothel to survive. Noblezada acknowledged that she drew on her own experience as a newcomer to portray Kim’s wide-eyed innocence.

She was not naive, a point she stresses to those who would conflate her with Kim, but her “blank page” approach to the show gave her a chance to arrive at Miss Saigon with a new, more modern perspective. The musical was also doing some necessary growth of its own, as it struggled to shake off its troubling past and establish itself as a show that could still be moving and relevant to a new, more socially conscious generation.

The differences between this production of Miss Saigon and its previous incarnations are subtle, but the cumulative effect is a show that feels more respectful of the historical truth that it’s mining for a fictional love story. While critics may continue to deride the musical for a “white savior narrative” — an argument with merit — the new lyrics deepen the characterizations of Kim and the other Vietnamese characters, like the world-weary prostitute Gigi (Rachelle Ann Go). Work is still being done in moving the production from London to New York: There’s a moment in Act 1 when Kim and Chris have an impromptu wedding ceremony complete with traditional Vietnamese chanting. Prior to the Broadway revival, the words had been gibberish. Now the lyrics are, finally, in Vietnamese.

And then there’s the commitment to casting only actors of Asian descent in Asian roles, a seemingly obvious choice that nevertheless continues to plague theatrical productions across the world — note the cast lists for countless regional productions of The King and I and The Mikado. For Noblezada, whose father is Filipino and whose mother is Mexican-American, meeting the London cast of Miss Saigon for the first time was breathtaking in large part because of the collective diversity of the room. “At my school it was like me and one other Asian person,” she said. “But now it’s like you’re putting this show on together and you have the opportunity to stand together and put on this masterpiece. It was like meeting a new family that I felt like I knew already.”

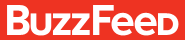

Noblezada in a scene depicting the fall of Saigon. Michael Le Poer Trench and Matthew Murphy

On Broadway, opportunities for Asian-American performers are still limited. According to the most recent report from the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC), Asian-Americans made up only 4% of performers on Broadway and in New York City nonprofit theaters from 2006 to 2015. But during the same period, there have been some notable casting coups for Asian-American actors, including Ali Ewoldt as Christine in The Phantom of the Opera and Phillipa Soo as the titular character in the new Broadway musical Amélie. While these roles do little to shift statistics, they are high-profile opportunities for audiences (and producers) to see Asian-American actors in roles that were not written as specifically Asian or Asian-American.

Noblezada is passionate about representation, but she also has the perspective of a new generation for which many of these issues are already second nature. The practice of increasing visibility for performers of color by casting them in roles that aren’t necessarily nonwhite is something she has never really questioned. While Asian-American students were underrepresented at her high school, there were a large number of black students. When it came to school productions, “We didn’t give two craps about race,” she said, referring to her school’s practice of casting actors of color in any role. “It was so unimportant in terms of casting.”

Before she took on the role of Kim, Noblezada had a brief stint in Les Misérables to help her get used to a professional production. Again, she viewed her ethnicity as irrelevant to her casting. “I’m a Mexicasian who played Éponine,” she said. “Does that make sense to you? No, but I did it, and it was fun, and I still told the story.”

This matter-of-fact mindset is a major contrast to the anxiety and turmoil surrounding shows like Miss Saigon, which have struggled to correct past wrongs and keep up with an ever-changing world. Noblezada is eager to not let herself be defined by her age, but if there’s one area in which her youth is a clear advantage, it’s in the “why not” perspective she brings to the conversation of casting diversely. She’s not single-handedly modernizing Miss Saigon, but she’s well aware of what it means for people to see actors who look like them onstage.

Now, as more shows evolve and as others continue to broaden their casting, Noblezada finds herself in the position of being a role model to the next generation of performers, particularly actors of color. “I’m surprised, but I’m taking it. I’m grabbing it,” she said. “I’m saying, ‘Let’s do it together.’”