On the day the unprecedented same-sex kiss was to be filmed for the 1982 movie Making Love, the set was packed — and tense — after weeks of buildup. A couple of days earlier, producer Daniel Melnick told the movie’s co-star Harry Hamlin, “Two days! I’ll be there!” Sherry Lansing, the president of production at 20th Century Fox, the movie’s studio, was also looking forward to it. “Harry, we’ll be there!” she had said. Director Arthur Hiller led the production, and Melnick and Lansing stood behind the camera with him. They were there to witness history, but also perhaps to gawk.

At the center of all the attention were the two actors, Hamlin and Michael Ontkean. They were both dark-haired, clean-cut, and a little nervous about the scene they were soon to perform. Ontkean played Zack, a 30-year-old Los Angeles doctor married to a network TV executive, Claire (Kate Jackson); and Hamlin played Bart, a physically fit, successful novelist, a player, an out gay man — and the object of Zack’s closeted affection.

Wings, 1927 (top) and The Sergeant, 1968 (bottom). Courtesy Everett Collection / Archive Photos / Getty Images

Men had kissed before onscreen, certainly. In Wings, for instance, the 1927 movie that won the first Academy Award for Best Picture, two fighter pilot friends who had been rivals for the same woman share a kiss as one of them is dying. Men had kissed in European films, most notably in 1971’s Sunday Bloody Sunday, which was also about a love triangle. And there had been negative depictions of men kissing, like in the background of the murderous BDSM club in 1980’s Cruising, and in 1968’s The Sergeant, when Rod Steiger’s character goes crazy and assaults the object of his affection with his lips.

But an affectionate kiss between men who care for each other? In a movie made in Hollywood, and produced by a major studio? That was historic.

“It was completely unheard of that two men would embrace and then their lips would touch on film,” Hamlin remembered over breakfast at a deli near his home. “‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ was the response I would get when I would tell people I was going to do it.”

Long before television led the way in showing LGBT life — first on reality shows, later on scripted TV — Making Love gave something to gay audiences, who were used to being represented as monsters or sissies. Its screenwriter, Barry Sandler, had specifically set out to show a positive view of gay people. In Zack, Making Love presents a kind and prosperous hero. “Growing up, we were inundated, my generation, with all these negative images of gay people,” Sandler, who was 35 when the film was released, said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. “They would be either suicidal or desperate or pathetic or murderers. Or the butts of jokes — big, flamboyant drag queens, the comedy foil. We all get our perceptions of ourselves from movies.”

A. Scott Berg, who received a “story by” credit for coming up with the idea for Making Love, and worked with Sandler, said: “We made the movie because we really believed in it, and believed it could make a difference. I heard Barry say at least 10 times, back then and as recently as a couple of years ago: ‘I want to make this movie so some kid in a small town in Missouri will know that he’s not alone. And it’s going to be OK.’”

But Making Love, which is out on DVD but isn’t available to stream, has in part faded from history, 35 years after its release. Though prescient on same-sex marriage, it’s not canonical to younger LGBT people, nor are any of the small wave of gay-themed movies — Personal Best, Partners, Deathtrap, and Victor/Victoria — released in 1982: a mini phenomenon that caused the New York Times to declare there was a “New Realism in Portraying Homosexuals.” In the Arts & Leisure section, Leslie Bennetts wrote, “The emergence of a cluster of films dealing with homosexuality constitutes something of a milestone in the history of a topic that long was strictly taboo.”

But something else happened in 1982: the coinage of AIDS, an acronym the CDC came up with in September of that year to describe the phenomenon of whatever was causing people — mostly gay men — to die of pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma by the hundreds. The health crisis caused panic in the gay community, and a re-stigmatization of LGBT people. With so many gay men dying, pop culture, theater, and art realigned around stories of HIV and AIDS for the next two decades.

Before the release of Making Love, Marvin Davis, the new owner of 20th Century Fox, stood up during a private screening and bellowed at its producer, “You made a goddamn faggot movie!” before stomping out. When the movie came out on Feb. 12, 1982, it caused some members of the audience to boo, jeer, and sometimes walk out themselves. And when it came time to air on network TV, there was a fight to keep in even the first brief kiss between Zack and Bart — a longer one in close-up was edited out.

Making Love was Hollywood’s first gay romance. And for many years, it was its last. There are movies, Berg said, that “help us get over a problem” simply by showing marginalized people living their lives and being human; he sees Making Love as one of them. “Here’s this movie that’s 35 years old, and it still touches people,” he said. “Its impact is still felt. It’s significant.”

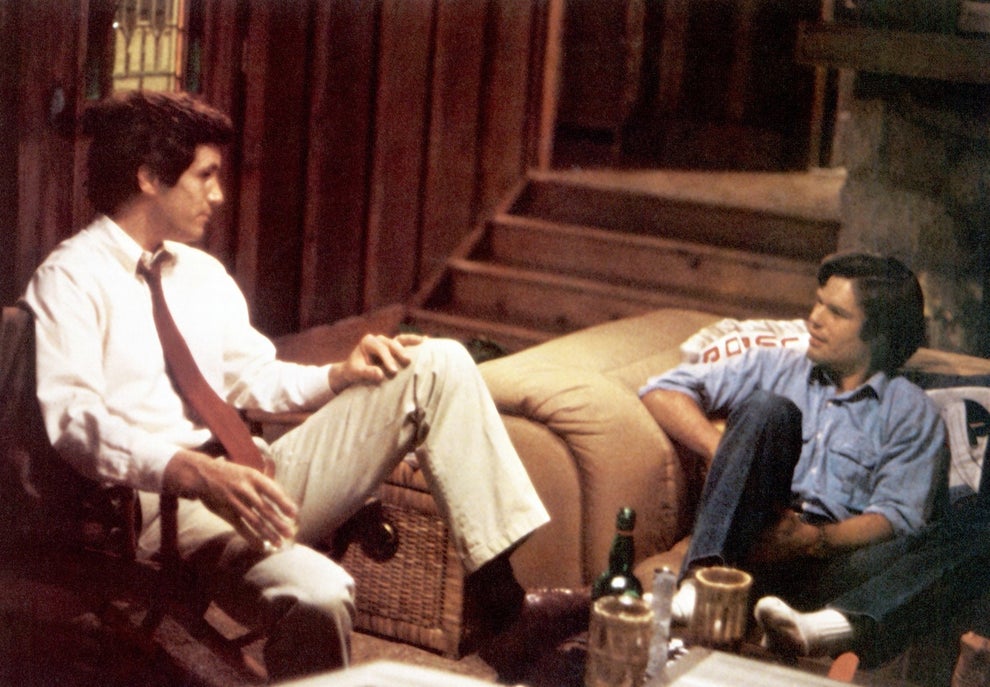

Harry Hamlin and Michael Ontkean in Making Love, 1982. 20th Century Fox / Courtesy Everett Collection

In 1978, at age 28, Berg had published his first biography, Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, and won the National Book Award for it. After its success, he was commissioned by the estate of Samuel Goldwyn, one of the movie moguls behind MGM, to write Goldwyn’s official biography. But there were lawyers involved, so as he waited to be able to sell the book to a publisher, Berg had time on his hands. His father, a television producer and writer, suggested that he come up with an idea for a movie. Berg thought about all the men he knew, himself included, who were in the process of coming out.

“I thought, Wow, the gay movement has reached a stage of critical mass here where this is happening,” Berg said. “With that action is coming an equal and opposite reaction of homophobia, so this would be a very good time, I thought, to do the first positive gay movie.” He wondered whether there could be a movie that did for gay people what Stanley Kramer’s 1967 classic Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner — about a rich, white couple, who consider themselves to be liberal, grappling with the idea that their daughter plans to marry a black man — had done for interracial marriage.

Sandler, meanwhile, was feeling stuck in his career. He’d had a number of screenplays produced — a Raquel Welch roller derby movie in 1972 (Kansas City Bomber), a Goldie Hawn comedy in which she played a con artist in 1976 (The Duchess and the Dirtwater Fox), and an Agatha Christie adaptation in 1980 with an all-star cast (The Mirror Crack’d, with Angela Lansbury, Elizabeth Taylor, Kim Novak, Tony Curtis, and Rock Hudson). He and Berg had dated, and were friends, and, knowing how Sandler was feeling about his writing, Berg went to him with his idea for the movie, which by then he had outlined on notecards. Sandler was intrigued, but worried about coming out publicly. “I wasn’t closeted, but it was a big leap to writing a gay movie and going on TV and saying, ‘I’m gay, and I wrote this movie,’” he said. “I really resisted it for a long time. I also resisted digging into such personal shit. But Scott was relentless.”

Berg wasn’t ready to come out publicly himself, and with his career as a biographer in mind and the Goldwyn deal looming, he didn’t want a screenwriting credit, which might give the appearance to the book publishing industry that he was switching careers. He proposed a partnership with Sandler in which they would use the story Berg had laid out and refine it together, with Sandler writing the screenplay. Berg said, “I kept saying: ‘This is a really timely thing. It’s happening now. We’ve really got to get out there with it.’”

“He finally wore me down after a while,” Sandler said. The idea for Making Love at this point was that a closeted, married man (the Zack character) meets a charismatic writer (the Bart character) and falls in love with him. Zack then has to deal with coming out to his wife, who wants to have a baby and is devastated, while also trying to domesticate the relationship-averse Bart.

Part of Berg’s struggle while coming out was that he wanted a monogamous relationship, which was not typical among gay men then. “If I am gay,” he remembered thinking, “if I am coming out, can I have a real relationship, a real romantic relationship? Can I settle down with somebody?” He put those thoughts into Zack, the homebody. “Barry was very much out,” Berg continued. “And Barry was very Bart. I said the dynamic between us is instant drama, because we come from two such different places.”

Behind the movie’s plot and characters was the still-radical idea that homosexuality was normal, and should be presented as such. The Stonewall riots, the birth of the modern LGBT civil rights movement, had taken place in 1969. It was more than 10 years later, and Berg felt there was a “gathering movement” of people ready to come out.

Sandler said that their message — that gay people were like everyone else — was explicit and intended, and in addition to wanting to provide LGBT audiences with representation they’d never had before, they wanted to be instructive to straight moviegoers. “We wanted these people to be successful and together and attractive,” Sandler said. “We wanted to present them like it’s your neighbors, or your family. People you relate to, people you understand.”

It was also meant to be an antidote to the recently released William Friedkin movie Cruising, in which a detective played by Al Pacino goes undercover to find a serial killer in New York City’s gay leather scene. “Cruising fed into that perception that all gay people were desperate characters — low-life, scummy characters,” Sandler said.

It was 1980, about to be the dawn of the Ronald Reagan era, and Sandler didn’t want to write the screenplay without a studio backing it. “Studios were scared at the time,” he said. He remembered thinking: “I don’t want to write an original screenplay, and spend a chunk of my life throwing out my heart and soul, and nobody would want it.”

In their effort to get a studio behind the project, Berg and Sandler were trying to sell both the plot, which was sure to be seen as sensational, and the ideas behind it. Berg had a friend, Claire Townsend, who was about to start a job developing movies under Sherry Lansing at 20th Century Fox. Lansing, the first female president of a movie studio, was known for her passion for topical films, and while at Columbia Pictures she had overseen The China Syndrome (about the threat of a nuclear reactor melting down) and Kramer vs. Kramer (about a father wanting custody of his son after a divorce). “I think the cutting edge–ness will appeal to her,” Berg remembered thinking of Lansing.

He had lunch with Townsend on the Friday before she began her job at Fox. “I was two sentences in,” he said, “and she said, ‘I’ve got to do this.’” Since Townsend hadn’t even started her job, Berg didn’t expect to hear from her for a while.

“Sunday night, she called me up. She said, ‘I talked to Sherry this weekend, and I told her about your idea, and she loves the idea.’”

Lansing remembered Townsend telling her that she’d heard “a really interesting pitch.” “She said, ‘This man comes to his wife, and he tells her that he’s leaving her. But he’s not leaving her for another woman, he’s leaving her for a man!’” Lansing said in a phone interview. “And I went, ‘Oh my god, that’s brilliant!’ It was just that concept. I said, ‘I love it! Go make the deal.’”

“It was thrilling,” Lansing said. “It was just a gut-level reaction that this was an amazingly good idea for a movie on many, many levels. And something that I instantly wanted to make.”

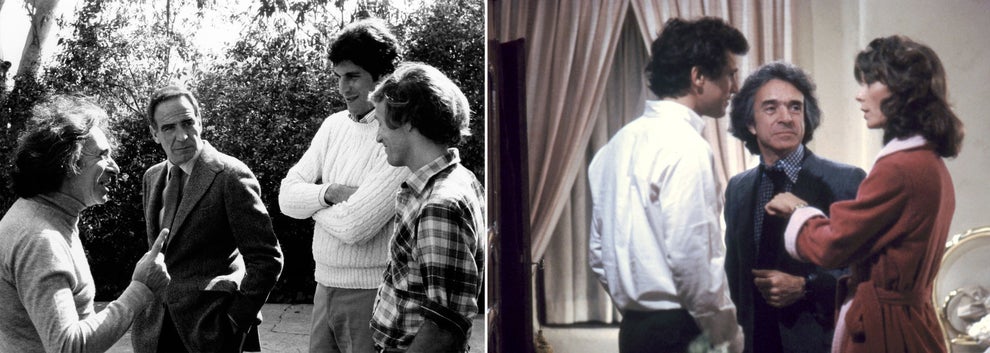

Director Arthur Hiller with Daniel Melnick, producer Allen Adler, and Barry Sandler; Hiller on set with Ontkean and Jackson. 20th Century Fox / Courtesy Everett Collection

“It took two women to say yes,” Sandler said. “I don’t think any male studio head, straight or gay, would have sanctioned that film at the time. God bless ’em, they did it. They said they wanted to be pioneers. And Sherry stood up and said, ‘I want to make this movie,’ and was pretty tough about it.” (The wife character would eventually be named Claire, after Townsend, who died in 1995.)

After Sandler wrote the script from Berg’s story, and the two of them worked together to revise it, they submitted it to Townsend, who loved it. Townsend and Lansing then gave it to Melnick, for whom Lansing had worked at MGM and Columbia Pictures, and whose production company was at Fox.

Melnick, who died in 2009, was known as a bold tastemaker and an influencer. The New York Times once wrote of him: “Strewn with pieces of modern art and banks of white chrysanthemums in silver planters, his house is as dramatically black-and-white as a chessboard. Handsome, fiftyish, lithe and tanned, he wears with grace the $100 Turnbull and Asser shirts that are custom-tailored for him in London.”

He said yes right away. Sandler said, “Danny Melnick called me at 1 in the morning when he finished reading it. One in the morning! He said, ‘I’ve never been so moved.’”

With an important producer attached to Making Love, Berg and Sandler began to make a list of directors. “We had been thinking of younger directors, and in many cases, gay directors who weren’t necessarily even out, but were either gay or had a gay sensibility,” Berg said. Then Melnick called, saying that Lansing had an idea for one: Arthur Hiller. Berg was shocked. Hiller was in his fifties at the time, and very straight: He had been with his wife, Gwen, since their childhoods in Edmonton, Canada. On top of that, Hiller embodied mainstream success. Berg said, “He was just coming off one of the great 10-year runs a director ever had: The In-Laws, Popi, Love Story, Hospital, Plaza Suite. And I’m thinking, And now Arthur Hiller wants to take on a little three-person drama about a guy coming out of the closet? Good luck.” They were excited about the idea, but it “seemed impossible,” Berg said.

Hiller was supposed to direct The Verdict for Fox, but the Making Love script won him over. The director died this past August, but in a December 2013 interview in his Beverly Hills home, Hiller, then 90 and sipping a Diet Coke, said, “I liked the fact of what it was saying. It felt good to me.”

Berg said, “This I later heard from Arthur himself — he said, ‘I read the script, and I cried. And I thought, I really don’t know these people. So I read the script a second time, and I cried even more.’”

Hiller dropped The Verdict in order to do Making Love.

With an urgency that the timeliness of the movie demanded, and rumors that the larger-than-life, brutish Denver oilman Marvin Davis would soon buy Fox, it was time to start casting.

They tried to get stars first, going after Harrison Ford, just after of Raiders of the Lost Ark (“No way,” Sandler said); Richard Gere; William Hurt; Tom Berenger; and Michael Douglas, with whom Lansing and Melnick had done The China Syndrome. “He was sort of toying with the idea, but everyone around him said, ‘Don’t do it, don’t do it. Don’t ever kiss another man onscreen,’” Sander said. “Sherry was really trying to push him for it. And he kind of wanted to. But in the end, he didn’t.”

Hiller said, “In the old days, you know, Rock Hudson had to get married to get people not to realize he was homosexual.”

“It was really tough,” Berg said. “This was now 1981, it was still before playing a gay character was Oscar bait. This was a really dicey thing. And I know so many actors whose agents or friends said, ‘This will be suicide for you.’”

No one was panicking, though. “They were determined to make the movie. Melnick, he said, ‘If we don’t get stars, we’ll just get the best actors we can get.’ The star of the movie is the idea,” Sandler said.

The strategy shifted away from star power to recognizable and relatable talent. Harry Hamlin was an upcoming, well-trained actor (Yale and the American Conservatory Theater). He had played the title character in the 1979 TV miniseries Studs Lonigan and was to star in the soon-to-be-released Clash of the Titans. He was also famously heterosexual, having begun a relationship with the original Bond girl, Ursula Andress, on the set of Clash of the Titans — she was the Aphrodite to his Perseus — that resulted in her becoming pregnant when she was 44 and Hamlin was 28. (Public figures becoming unwed parents was then in itself a scandal.)

At the time, Hamlin was being offered parts in genre movies that “were really stupid,” he said. When he read the script for Making Love, it appealed to him as an alternative. “This was a film about a real thing that was happening in the world,” Hamlin said, “about something that was controversial. It was a real social phenomenon. Not a bank robbery, not invading bats, not aliens from another world.”

Harry Hamlin and Ursula Andress, 1979; Kate Jackson (middle) and her Charlie’s Angels co-stars; Jackson and Michael Ontkean in The Rookies, 1973. Caterine Milinaire / Getty Images, Spelling-Goldbe / REX / Shutterstock, ABC Photo Archives / Getty Images

He was also eager to work with Hiller. “I said, ‘Were it not that I had to play a gay guy in this, I would love the script,’” Hamlin remembered. He consulted his close cadre of friends in the industry, who all advised him not to do it. But his agents thought he could “get away with it” because of his relationship with Andress. He remembered them saying to him, “She’s considered the biggest sex symbol in the world, and you’re doin’ her and you have a kid with her and you have a relationship with her. Everybody knows that you are straight as a result of that.”

He decided to take the role of Bart. “I have always had a kind of hubris, I think, that has served me well at times, and at other times, I’ve been rather stupid,” Hamlin said. “I always felt that I can survive anything. I don’t know. Maybe it’s some weird sense of immortality.”

In casting Claire, Hamlin, Sandler, and Berg argued for Brooke Adams, who had been in Terrence Malick’s esoteric Days of Heaven and — on the opposite end of the film spectrum — the well-received hit remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, both in 1978. Hiller wanted Kate Jackson, who had co-starred on the Aaron Spelling–produced massive hit Charlie’s Angels from 1976 through 1979 as Sabrina and was known, informally, as “the smart one.” Jackson left Charlie’s Angels after Spelling wouldn’t shift production so she could be in Kramer vs. Kramer in the part that eventually went to Meryl Streep (and won Streep her first Oscar): Jackson was, reportedly, furious.

Hiller said Jackson appealed to him because “she was a warm and charming person,” he said, and would bring that to the part. Claire, as her arc goes on, would also need to show that she still loves Zack, and eventually accept his decision. Hiller said, “She also brought the strength of being able to play a love relationship with her husband, and then lose him — and not lose her feelings for him.”

Melnick agreed with Hiller. Sandler remembered him saying: “For people who are kind of nervous about the subject matter, she would kind of be a safety valve. She’s been in everybody’s home. She’d guide them through this. And then at the end, when she comes around, and she says, ‘He has to do what he has to do,’ people will relate to her, and they’ll identify with her.” As Berg and Sandler recalled, Jackson was looking to make it in film and wanted the part of Claire. (Jackson did not respond to several requests for an interview.)

Ontkean and Jackson had appeared together in the early ’70s ABC cop drama The Rookies, which was how his name came up for the role of Zack. The curly-haired Canadian actor had made an indelible impression in film in 1977’s Slap Shot — a Paul Newman comedy about a down-and-out hockey team — during which he performed a striptease on the ice. “I had long been pushing Michael Ontkean,” Berg said. “He was somebody I just really liked in movies.” Reached by email, Ontkean would not agree to be interviewed for this story.

It was February 1981. The cast was set, and it was time for production to begin in Los Angeles.

Hiller, Sandler said, wanted him on set every day as a “technical adviser,” but what he really meant was adviser on all things gay. He even asked Sandler to take him to a gay bar in East Hollywood. “He was fascinated,” Sandler said. “We went to a really dark, grungy place with a backroom — he couldn’t get over it! He had never seen anything like that in his life. He was totally nonjudgmental about it, but he was fascinated as a filmmaker, as a creative person.” Hamlin went to a gay bar, too, and some people recognized him. “I went in alone,” Hamlin said. “I remember saying, ‘I’m researching.’ They were like, Yeah, right, here’s my number.”

Sandler, an associate producer on the movie, did make one adjustment as Making Love’s gayness expert. In doing the production design for Bart’s Hills-set house, James Vance had put a huge portrait of Judy Garland on the mantelpiece. “I went, ‘No way,’” Sandler said. “I said, ‘Look, we all love Judy Garland, but this character would never, never have that up.’ I know a lot of gay people who love Judy Garland; I’ve never seen a life-sized portrait of her.

“I went to Arthur, I said, ‘Arthur, you can’t.’ He said, ‘Fine, fine, go to props, find something you like, and we’ll do it.’

On the day of the kiss, Sandler remembered Ontkean and Hamlin seeming “a little on edge.” “We went to lunch, and Arthur ordered some wine to make sure they had a couple of glasses to loosen them up,” he said.

They hadn’t rehearsed the scene beforehand. Hamlin had argued that since it was the first time Zack had ever kissed a man, it should appear like a new experience.

“I said, ‘This is how this ought to go: This should be a really sweet, loving first kiss,’” Hamlin remembered telling Ontkean. “‘I really think if we do this in the close-up, our lips just come really close to each other,’” he continued, speaking through pursed lips to describe it. “‘And barely touch like that. A really kind of romantic, miracle moment.’”

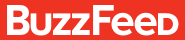

In the scene, set in Bart’s house, Zack’s dancing around their tension and saying things like, “It’s not as if I’m gay. I’m just curious, you know?” A frustrated Bart, thinking Zack is never going to make a move, gets up to pour another drink, at which point Zack walks up to Bart and kisses him briefly. They then go arm in arm into the bedroom, and begin to undress each other. The camera gets closer, and they begin to kiss again — a longer one.

Bart and Zack then fall into bed with each other. “It was in the script: They make love,” Hamlin recalled. Both actors balked from the beginning, saying that for them to be naked and simulating sex was too far ahead of its time. Hamlin said: “Both Michael and I said to Arthur at the beginning: ‘We’re not doing that. We’ll kiss. We’ll be in bed together. But we’re not going to do simulated sex.’ It’s just inappropriate.”

Everyone agreed — until Hiller changed his mind. “He went to the guys, and at that point, it was one bridge too far,” Sandler said. “Understandably — it was enough.”

“They decided they needed a fucking scene,” Hamlin said. “They went down and got two male hookers from Santa Monica Boulevard that looked sort of like me and Michael. Bring them back up, and shot them fucking in the bed.”

This sounded potentially apocryphal, but Sandler confirmed that, yes, it had happened. “Arthur came to me and said, ‘Can we find two extras that look like them?’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘Do you think we could go and hire a couple?’ I said, ‘You mean on Santa Monica Boulevard?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Lemme give it a shot.’”

Sandler and the movie’s location manager went to West Hollywood and found a man who looked like Ontkean, and then another who resembled Hamlin. “I don’t know if both were hustlers,” Sandler said. “Maybe one was. They wanted to be in movies.”

It’s not an explicit scene, and is shot from a distance. “I didn’t want to do it in the normal way — going in close, and seeing the legs or seeing the arms,” Hiller said. “All those things that have been done in many love scenes. I thought, That’s not right for this.”

Nevertheless, the news of the body doubles went over terribly with Ontkean and Hamlin. “I remember it was after that, Michael was going, ‘This is fucked up,’” Hamlin said. “We had this conversation, him and I. I said, ‘No, it will be OK. We didn’t do it, it wasn’t us.’ But it did feel like a betrayal.”

Hamlin said the filming went smoothly otherwise. “Arthur was a wonderful director; the cinematography was fantastic,” he said.

William Reynolds, Making Love’s editor, had given Hamlin early indications that the movie — and his performance — would be well-received. Reynolds, who had won Oscars for editing The Sound of Music and The Sting, and also had edited The Godfather, called Hamlin, sounding excited. “He said, ‘Harry, I just finished the first cut of the movie: You’re going to get an Academy Award nomination for this,’” Hamlin remembered.

On the studio side, though, there was trouble brewing. Davis, the boorish wildcatter, had indeed bought Fox in June 1981. In the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, based on Vito Russo’s 1981 book of the same name about LGBT representation in movies, Melnick tells the story of screening Making Love for Davis — without naming him.

“The ownership of the studio changed hands,” he says. “A new person came in who was not from the film world, nor the intellectual world, nor the world of letters and arts. And I had the unpleasant task of running in a screening room for this man and his lovely wife and daughters the rough cut of the film. None of my colleagues would be there; they were all afraid. So I was there by myself, sitting in the back. He was sitting up front in the small screening room. He was squirming all during the movie; he couldn’t sit still. The part in the movie when the two men embrace and kiss, he jumped and said, ‘You made a goddamn faggot movie!’ and stalked out.”

Lansing did not remember that extreme reaction from Davis, but she did recall that he was in a “state of shock.” “I remember we went to Jimmy’s restaurant afterward, and there was silence. I was, like, stunned!” Lansing said. “I remember him saying, ‘So this is the movie! Where’s my Doris Day comedy?’”

“It was complete naïveté!” Lansing said. “I just thought it was this wonderful movie, and how could anybody not love it?”

Hamlin, in later years when he was the star of L.A. Law, became friends with the Davises, and they invited him to their charity event to benefit children with diabetes. At a certain point in the evening, the couple stood up and told stories about how they knew the invited guests. When they got to Hamlin, Barbara Davis took over the story. “‘Well, it was just after we bought the studio. And we were so excited to be part of the new Hollywood community,” Hamlin remembered Davis saying. “We owned a studio! 20th Century Fox, no less. The best studio. We hadn’t been there for more than a couple of months, and suddenly they’ve asked me if we want to go and see the first movie that’s going to be released by the studio.”

“Halfway through the movie,” Davis continued in Hamlin’s recollection, “we see these two men kissing each other! Marvin practically threw up. He turned to me and said, ‘I think we should sell the studio.’”

Rather than discouraging them, Davis’s negative reaction was galvanizing for the Making Love team. “I remember hearing that and thinking, Great!” Berg said. “It really emboldened everybody, I think, Arthur included. Now we have a cause. Because Sherry was not budging, Claire Townsend was digging in, Dan Melnick you didn’t cross. He was a tough customer. And I think Arthur suddenly thought, Ooh! This is important. It was, in fact, a nice moment. Oh, so there is homophobia.”

Making Love’s marketing budget was reportedly $5 million (after an $8 million production budget), according to Boze Hadleigh’s 1993 book The Lavender Screen. It was marketed both to gay audiences (Making Love matchbooks were distributed in gay bars) and straight ones (the poster featured Ontkean, Hamlin, and Jackson standing together, though they never appear together onscreen). The trailer teased (and warned of) the movie’s plot: “Twentieth Century-Fox is proud to present one of the most honest and controversial films we have ever released,” with more text stating that the movie “breaks new ground in its sensitive portrayal of a young woman executive who learns that her husband is experiencing a crisis about his sexual identity.” It continues: “Making Love deals openly and candidly with a delicate issue. It is not sexually explicit. But it may be too strong for some people.”

Making Love received mixed reviews. In a biting New York Times review, Janet Maslin wrote that it wasn’t for “those who value seriousness, quality, or realism above sheer foolishness,” and that once Zack comes out to Claire, “the movie turns rip-roaring awful in an entirely enjoyable way.” Variety, however, wrote that the movie “stands up well on all counts, emerging as an absorbing tale.” In the Chicago Tribune, Gene Siskel praised the coming-out scene as a “nonstop torrent of emotion,” called Jackson “a revelation,” and wrote that the movie’s importance is that it “truly equates homosexuality with heterosexuality.” He concluded “it does this while telling a fascinating and well-acted story.” Roger Ebert, on the other hand, called it “predictable,” and “essentially a TV docudrama.”

Ontkean and Hamlin in the scene leading up to their first kiss. 20th Century Fox / Courtesy Everett Collection

There was also some criticism from the gay community. ”It’s a very negative prototype, because it portrays gay relationships as a bad imitation of middle-class straight relationships,” an activist named Arthur Bell decried in the New York Times story about 1982’s gay-movie trend. ”And it doesn’t work that way; imitating straight lifestyles doesn’t work for homosexuals. The movie is absolutely not representative of the gay population.”

There were walkouts after the kiss scene, an experience Sandler had firsthand when he went to see the movie with family in Miami on opening night. “I see a huge line around the block,” he remembered. “I see the line is mostly straight couples. I say, ‘Do they know what this movie is? All these straight couples?’ Part of me is thinking, Oh, that’s nice, everybody suddenly got enlightened. On the other hand, I’m thinking, Did Fox sell this movie not telling them what the movie is?“

The kiss between Zack and Bart takes place a little more than 45 minutes into the movie, and as the sexual tension built between the characters, Sandler noticed “uncomfortable titters.” After the kiss, it was “pandemonium.” He said, “You thought you were on the Titanic or something. People started streaming up the aisles. I couldn’t handle it; I had to leave. It was really upsetting. I’m thinking, They had no idea what this movie was?“

Hamlin took the negative reviews and criticism hard. “I felt like I was alone in a big ocean without a life preserver,” he said. “There was nobody I could call to talk to about it. My friends didn’t want to talk about it. My agent was gone; he’d left and gone to Mexico. My publicist was unavailable. Everybody was unavailable!”

He continued: “I would say the response to that movie had a visceral effect on my sense of self as an artist — of course. You do something, you’re proud of it, you think it’s great. Then all of a sudden, it’s tarred and feathered, and run out of town.”

In terms of box office, Making Love opened strong, taking in more than $3 million — impressive for its time — on Valentine’s Day weekend. “I remember everyone was excited about the opening weekend,” Lansing said. “And then the second weekend wasn’t as good.” Though Box Office Mojo has the movie topping out at $11.9 million, Hadleigh wrote in The Lavender Screen that it made between $16 and $18 million in the US, $7 million overseas, and did well on home video, making it profitable. (When Fox eventually released Making Love on DVD in February 2006, it was to capitalize on the critical and commercial success of Brokeback Mountain, which was riding high on its eight Oscar nominations.)

But whether Making Love was a hit or not was beside the point. “We certainly didn’t make this movie to make money,” Berg said. “We made the movie because we really believed in it, and believed it could make a difference.”

After Making Love’s release, Jackson returned to series television, starring on the CBS adventure drama The Scarecrow and Mrs. King, which ran from 1983 to 1987. Her last scripted television appearance was as a guest star on Criminal Minds in 2007. According to IMDb Pro, she no longer has professional representation.

Ontkean went on to play a lead in several movies, most notably 1984’s The Blood of Others (opposite Jodie Foster), 1987’s Maid to Order (with Ally Sheedy), and 1988’s Clara’s Heart (with Whoopi Goldberg, and the film debut of Neil Patrick Harris, who played the son of Ontkean’s character). In 1990, he co-starred on Twin Peaks, David Lynch’s TV sensation, as Sheriff Harry S. Truman.

Ontkean (right) as Sheriff Truman in Twin Peaks, 1990. ABC Photo Archives / Getty Images

Despite his successes afterward, Ontkean seemed to view Making Love as a bad experience; he tried to stop the directors of The Celluloid Closet from using the kissing scene in the movie after they approached him for an interview.

“He wanted nothing do with us,” said Jeffrey Friedman, the documentary’s co-director, in a phone interview. “And now that I’m thinking about it, he was obstructive.” (The clip is in the documentary.)

Berg remembers Ontkean fondly, though. “What I’m about to say I mean in the most loving way: Michael was always a little crazy,” he said. “And I think he’s wonderful in the movie. He’s got such a nice quality about him. But he was a little cuckoo — in a nice way.” Ontkean has retired to Hawaii, and the last movie he appeared in, The Descendants with George Clooney, was filmed there. He will not appear in the revival of Twin Peaks. In his sole email response to BuzzFeed News in June, he wrote: “Am not on computer very often, and on telephone even less. With all that’s happened in the last 34 years, it doesn’t seem like a low-budget, pre-AIDS, pre legal marriage melodrama has anything to contribute.”

Hamlin, who felt he was on a course primarily to be in movies after Clash of the Titans, felt that Making Love derailed that. “No executive wanted to have me — because I could be gay, or I could be bi,” he said. “They couldn’t have me in a movie kissing a girl. It wouldn’t be right.”

For a while, Hamlin went back to TV miniseries, and then in 1986 began starring on L.A. Law, an immediate success that led to him being named People’s “Sexiest Man Alive” in 1987. After leaving L.A. Law in 1991, he starred in TV movies, and had guest arcs on — among other dramas — Veronica Mars, Shameless, and Mad Men, for which he was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama.

When asked whether he regrets taking the role of Bart in Making Love, Hamlin is unequivocal: “Absolutely not. I’m really proud of having done that, and I would do it again in a second. Under the same circumstances. And knowing what would happen after.”

“To this day, there’s probably someone in this restaurant who would like to come up to me right now and talk to me about it,” he said. “Literally, if I go out, on a daily basis, people come up to me and say, ‘Thank you for making that movie.’ That’s the one thing that I get much more response from than anything else. And it’s always: ‘Thank you for making that movie. It changed my life.’”

Hamlin and Susan Dey in L.A. Law. 20th Century Fox / Courtesy Everett Collection

He told a story about a student in his acting class who was from Caracas, Venezuela. “He came up to me when he first came into the class, and he was shaking,” Hamlin said with tears in his eyes. Overcome with emotion, he had to stop speaking. “I’m a little emotional about this,” he said, composing himself.

“He said, ‘I can’t believe I’m standing with you. You changed my life. The reason I’m here in LA, and the reason I left Venezuela, is because I saw your movie, and it inspired me to tell my parents that I was gay. And to come to Los Angeles.’ That has happened innumerable times. It had a huge effect on young gay men who couldn’t make a decision, couldn’t figure out what to do.’”

Lansing expressed a similar sentiment. “You think back on, What am I most proud of? I’m proud that we were able to say yes. All the credit goes to the filmmakers and all the talent associated with it. But just to be able to facilitate that is something that I’m proud of. I just remember loving the movie, and it just being a joy.”

Zack and Bart don’t end up together in Making Love. Zack tells Bart he loves him, and Bart, a pill-popping wild child who doesn’t want to be attached, turns Zack away after he leaves Claire. Zack and Claire do have one last important conversation before a flash-forward at the end that crystallizes the movie’s ideas one last time. She says they should get help, and go to a psychiatrist. Zack responds: “It’s not an illness. I am not gonna change!”

They go back and forth, with Claire trying to bargain with Zack. But he is sure of himself — finally — and of his decision. He tells her he’s going to move to New York, get a job at Sloan Kettering, and that they shouldn’t speak for a while. In one of the interstitial, direct-to-camera monologues that appear throughout the movie, Claire says, “It wasn’t easy to do what he had to do. But I know that he had to, and I —” She begins to cry, and then says, “And I know that’s the way it has to be. I just want him to be happy.”

A few years pass, and Zack has a stunning apartment near Central Park, and a handsome partner, who urges him to fly to Los Angeles for the funeral of Zack and Claire’s neighbor and friend. After the funeral, Claire invites Zack to stop by her house to meet her husband and son. To Zack’s surprise, Claire has named her kid Rupert, after the poet Rupert Brooke — what their child’s name would have been.

Jackson and Ontkean, Making Love. 20th Century Fox / Courtesy Everett Collection

As Claire walks Zack to his car, she asks him whether he’s happy. “Yeah. Yeah, I really am,” he says. “I’m happy too, Zack. For both of us,” Claire says. She touches Zack’s cheek, and he touches her elbow. It’s a sweet moment.

“That was the message: You can come out and not end up committing suicide, or have somebody kill you,” Berg said. “You can, in fact, ride off into the sunset with somebody and have a happy, successful life. That’s what did happen. It happened for me, anyway.”

Berg went on to write Goldwyn: A Biography; Lindbergh, for which he won a Pulitzer; and two other biographies; and he has been with his husband, Kevin McCormick, for more than 35 years. Sandler wrote the 1984 cult classic Crimes of Passion, directed by Ken Russell, and is an associate professor of film at the University of Central Florida. For Making Love’s big anniversaries, they have always screened the movie, with Sandler, Berg, and Hamlin attending to discuss it on a panel — and Hiller did, too, but this year will be the first one he’ll miss.

“The same thing always happened: There would be a Q&A, and people would start to ask questions,” Berg said. “And almost every person would stand up and say, ‘You know, I grew up in a little town in Alabama, and my parents had thrown me out of the house…’ Or, I remember one guy saying, ‘I drove a hundred miles to Lincoln, Nebraska — and I saw myself.’ And Arthur would hear these things, and oh, he would just sob!”

Same-sex marriage is now legal. We’ve grown used to fair, realistic LGBT representation on television, and, though movies have room to grow, 2015’s Tangerine and 2016’s Moonlight show how far films have come. Making Love, before AIDS engulfed everything for years, and before marriage was a realistic possibility, was a landmark along the way — a movie that helped personalize and normalize what had so recently been considered an illness, not to mention a crime.

After the movie opened, Berg went to see it with Hiller in a Westwood movie theater. As it unfolded, they experienced the usual run-up to the kiss — an edge creeping into the room. Then, Berg said, “When you got to the kiss, whoa! You’d hear people yelling at the screen, and within 10 seconds, people would just stand up and walk out of the theater. The night I was with Arthur, we saw 12 people stand up and leave.

“And Arthur turned to me and said, ‘I think we got it right.’” ●