1. Chill on the whitewashing.

This year saw Scarlett Johansson cast in Ghost in the Shell. It saw the entirety of the movie Doctor Strange. It saw Matt Damon as the lead in a movie about the Great Wall of China. And that’s just the shortlist of the ways Hollywood erased characters of color and put white characters at the center of PoC stories again and again.

At the very least, 2016 saw some people beginning to learn about the impact of these decisions. Tilda Swinton and Margaret Cho aired out an email conversation that discussed the controversy around Doctor Strange, and the film’s writer and director, Scott Derrickson, told The Daily Beast that he “didn’t really understand the level of pain that’s out there, for people who grew up with movies like I did but didn’t see their own faces up there.”

“The angry voices and the loud voices that are out there I think are necessary,” he said. “And if it pushes up against this film, I can’t say I don’t support it. Because how else is it going to change? This is just the way we’ve got to go to progress, and whatever price I have to pay for the decision I’ve made, I’m willing to pay.”

But Hollywood’s efforts to eradicate these issues have been nonexistent at worst and slow at best. The next step? Results, and preferably learning these lessons before the film is already made and out there.

2. Elevate more types of movie stars.

Every single time a movie gets made that, say, takes place in ancient Egypt and has a main cast of almost entirely white actors, the argument bubbles up that big Hollywood movies can’t get made without star power behind them. As Exodus: Gods and Kings director Ridley Scott said when defending the casting of Christian Bale, Joel Edgerton, and Aaron Paul as Moses, Ramses, and Joshua respectively: “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such. I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up.”

But every big name started as a no-name. Oftentimes they only gained recognition because someone took a gamble on them — taking the chance that they could carry a movie or TV show, believing that they had what it takes for audiences to connect with them. We need to give more people that chance, specifically people of different ethnicities, physical abilities, sizes, etc.

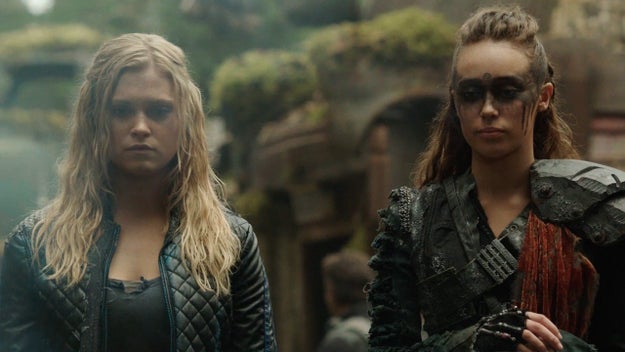

3. Put a moratorium on killing queer women characters.

Sometimes history just weighs too heavily on a storyline. And that is certainly the case when it comes to Hollywood’s tendency to kill off LBGT characters, especially on TV. This was particularly rampant in 2016 — so many fictional queer women died in such a short time that it almost felt like a concentrated effort. The 100, Orange Is the New Black, Empire, The Catch, The Magicians, The Walking Dead, The Vampire Diaries, Blindspot, Person of Interest, Pretty Little Liars, Masters of Sex — every single one of these shows and more killed off queer women characters in 2016. And fans stood up and demanded change.

The “bury your gays” trope elicits visceral reactions for a reason — including the heartbreak and exhaustion of seeing your sexuality so frequently associated with death, and the too-real ways the death of LGBT people is often on our screens as actual news. So we need a break. Preferably a long one. There are other ways to shake up your story than killing your queer characters.

4. Embrace more body types.

Really throughout the entire history of Hollywood, only a very small range of body types have been featured onscreen as desirable. And when Hollywood does decide to depict someone above a certain size — especially when that someone is a woman — they tend to make a pretty big deal about it. Think ABC’s sitcom American Housewife, the concept of which involves a Connecticut mother fixated on her position as the “second-fattest housewife in Westport.” Or NBC’s family drama This Is Us, which stars the talented Chrissy Metz, whose storyline revolves almost entirely around her obsession with losing weight.

When Disney strived to give its latest animated princess Moana a “more realistic body shape” — as director John Musker referred to it — the result was still an undeniably thin young woman. It’s a step forward from the notorious, physically impossible body images of Disney princesses past, sure — but a small one in the grand scheme of how far we have left to go. It’s impossible to be body positive if we’re not seeing the different types of bodies the world has to offer, and treating them with respect.

Around 67% of women in the United States are a size 14 or above, according to Refinery29’s 67% Project; only about 2% of images in the media reflect that. And of the movies and television shows that do, there’s an imbalance in the types of stories being told — they typically focus on the character’s size, and how the people around them react to it.

So much of what good film and TV does is tell human stories — so isn’t it dishonest to act like our bodies and the experiences that come from them don’t run the gamut?

5. Stop using sexual assault as a shortcut to character development.

In a lot of ways, it feels like we’re just starting to get TV series and films that really capture important different angles on sexual assault. There’s Jessica Jones’ attention to PTSD, and Sweet/Vicious’s mastery of tonal mixtures and dark humor, for example.

People deal with sexual assault and its ramifications every day, so it’s fitting to include it in the shows we watch every night when applicable. But many creative forces in Hollywood are using sexual assault as a fast and cheap means for character development. Game of Thrones, for example, may now be using its notorious history of sexual assault as a means of payoff by catharsis for its female characters, but that doesn’t erase questions about the choices they made along the way. “I would say out of [200 spec scripts], there were probably 30 or 40 of them that opened with a rape or had a pretty savage rape at some point,” The Exorcist executive producer Jeremy Slater told Variety about the sample scripts that come across his desk during the hiring process.

As Lost Girl and Killjoys creator Michelle Lovretta told Variety, “The nexus of sex and violence is the cinematic equivalent of a cheap sugar rush. It’s a fast-hitting combo of a lot of powerful inputs — titillation, taboo, character conflict, deep betrayal. In one scene, you could change the narrative arcs of a whole swath of your characters, and that kind of bomb can be pretty tempting for storytellers.”

That’s not only narratively cheap, it’s culturally noxious. Sansa Stark could have had her revenge without her rape.

6. Don’t leave people with disabilities out of the conversation.

As Alyssa Rosenberg wrote about the film Finding Dory for the Washington Post, “it’s pretty depressing that some of the most adventurous, fully realized characters with disabilities in American popular culture are cartoon fish.”

This past summer, protests against the film Me Before You were unprecedented in their scale and potential impact. The protesters took issue with the movie’s romantic portrayal of a man with a spinal cord injury who decides to take his own life via assisted suicide rather than continue to live with his quadriplegia. The push-back against Me Before You was just one example in a long history of people rejecting both misrepresentation and underrepresentation of people with disabilities in Hollywood.

“This conversation is so necessary because there are 56 million Americans with a disability,” actor Marlee Matlin said at the Disability Inclusion Roundtable in early November, according to Deadline. “That is 20% of the population. But if you judged our existence by what you see on TV, you would think we made up less than 1%.” As TV presenter Sophie Morgan told the Irish Examiner, “I would love to switch on my TV and see a disabled person talking about something they are genuinely interested in or acting out a part that doesn’t just focus on their impairment.”

“We as an industry keep talking about diversity,” she said. “We know we have a problem but when we start speaking about diversity, disabilities seem to be left out. We all remember the last Oscars for being too white. The Academy said its 2016 mandate is inclusion in all of its facets, but where is disability?”

7. Do your research.

When a person is writing about a culture or experience outside of their own lived knowledge, it’s important that they take on the responsibility that comes along with that by doing the research. Depicting BDSM? Writing about Model UN? A newly immigrated Japanese woman in the US in the 1940s? A trans character who’s job hunting? A black woman who’s getting her hair done? Read into what that might be like. Look into firsthand accounts wherever you can. Do.the.research.

“When artists create works about minorities with little research or attempt to understand the lived experience, they should expect questions about representation,” Alice Wong, founder of the Disability Visibility Project, told BuzzFeed in June. “It’s 2016, goddamnit.”

8. Balance your writing staffs.

QUEEN SUGAR writers room love! Saluting our writing team Tina, Ben, Denise, Jason, Anthony. Write on! #inclusivecrew

— Queen Sugar (@QueenSugarOWN)

The Writers Guild of America’s 2016 Hollywood Writers Report was called “Renaissance in Reverse?”, and it pointed out that into 2016, writers of color “remained underrepresented by a factor of nearly 3 to 1 among television writers.” According to a study by USC Annenberg that looked at nearly 6,500 writers, “for every one female screenwriter there were 2.5 male screenwriters.” These are big divides, and they impact what we see.

The famous Bechdel test has pretty basic standards for the depiction of women in fiction: Two women with names have to talk to each other about something other than a man. When there was at least one woman on a film production team, for example, only about 17% of movies failed the test, according to research on 4,000 titles. When a film was written entirely by women, only about 6% failed. When there were no women present, about half failed.

As the demand for representation rises onscreen, it’s important to also keep our eyes peeled for what’s going on behind the scenes. We saw an uptick in quietly groundbreaking portrayals of abortion on television this year, after all — and we can probably contribute a big chunk of that to the gender balance in each of those show’s writers rooms.

9. Hire more inclusively in every step of the production process.

Directors. Producers. Studio executives. Cinematographers. Costumers. From the bottom to the top of the production process, inclusion has proven to be a struggle for as long as the Hollywood machine has existed. And it’s not something that’s fixed simply, or all at once. The instincts and institutional walls blocking access are real and hard to combat. Only one in five shows during the 2015–2016 TV season credited a woman as the creator, according to a study by San Diego State University. On Adult Swim, that stat was one out of 34.

As BuzzFeed News’ Ariane Lange reported in September, one source who’d worked with Adult Swim noted, “The lack of female creators was flagged as a problem as early as 2005, and yet it appears no concrete steps have been taken to meaningfully rectify that discrepancy in the intervening decade.”

Working toward inclusion — and the many rewards that come with it — takes concerted time and effort, from absolutely everyone involved. Arrow co-creator Greg Berlanti, for example, vowed this April to hire 50% women and people of color to direct for the series. “It is your burden. You’ll learn that it actually ends up making the show better, and it’s really smart business,” he said to a room of directors in April.

He also pointed out a familiar conundrum: In order to get hired for a big Hollywood job, you often need to have already worked a big Hollywood job. But as with actors, creatives break into the system when other people decide to take chances on them. Colin Trevorrow had mainly worked on small projects and indies before Universal handed him Jurassic World and its $150 million budget. That certainly paid off for them. Currently, Ava DuVernay is the only woman of color to ever direct a major studio film with a budget of $100 million. But she’s not the only one capable, willing, and raring to do the job. Progress requires taking those chances, and in mixing up who exactly is getting them.