This post was originally published at an earlier date. Since our support for women’s rights is a forever kind of thing, we thought we’d update this story and any sold-out products to make it easier to support the cause.

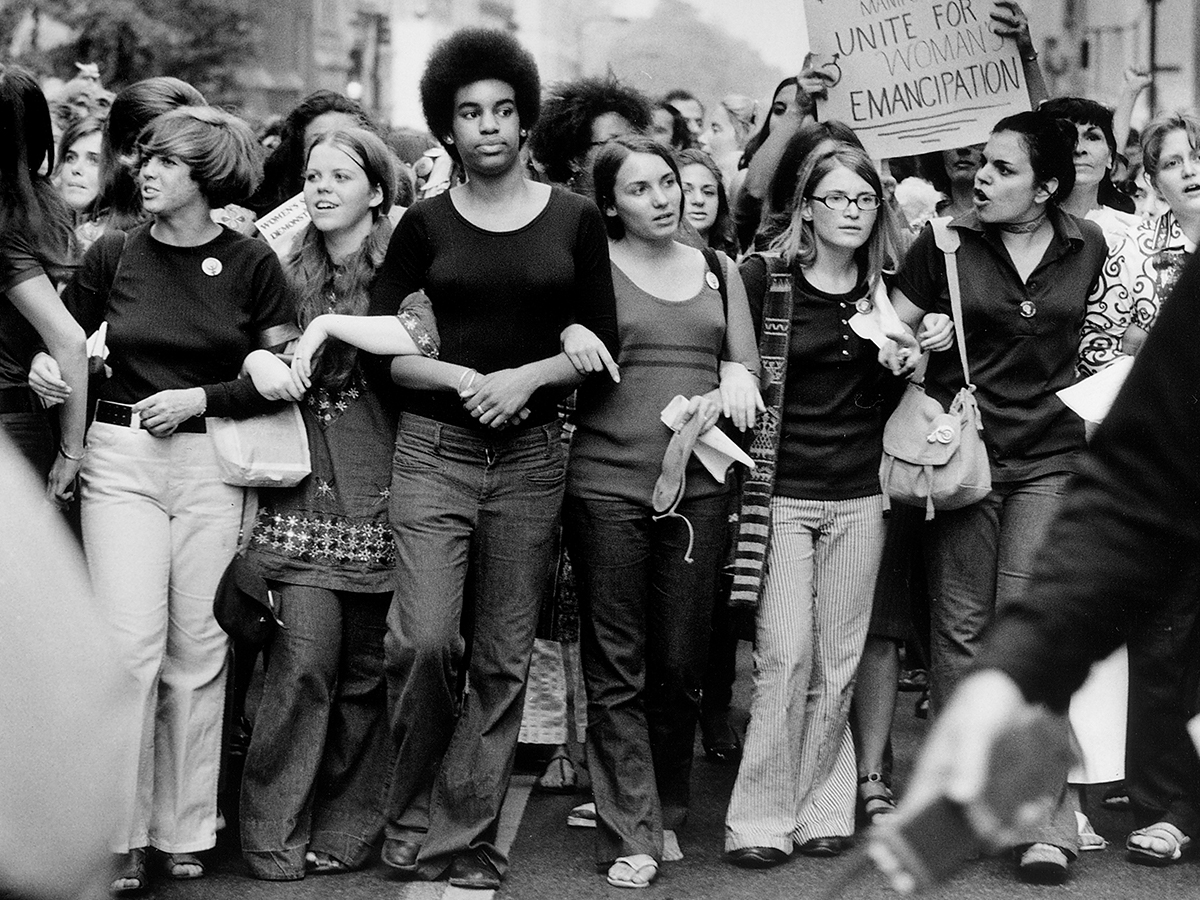

Some might say that style and politics are mutually exclusive. I’d beg to differ. Sure, how you dress can seem frivolous compared to the tragedies happening in the world, but the truth is that style has been and continues to be a tool for marginalized communities as a form of visual dissent. As we celebrate Women’s History Month and reflect on the history of how women fought for our right to participate in democracy (while wearing all-white, might I add), let us note the role style can play in the fight for the rights of all marginalized groups.

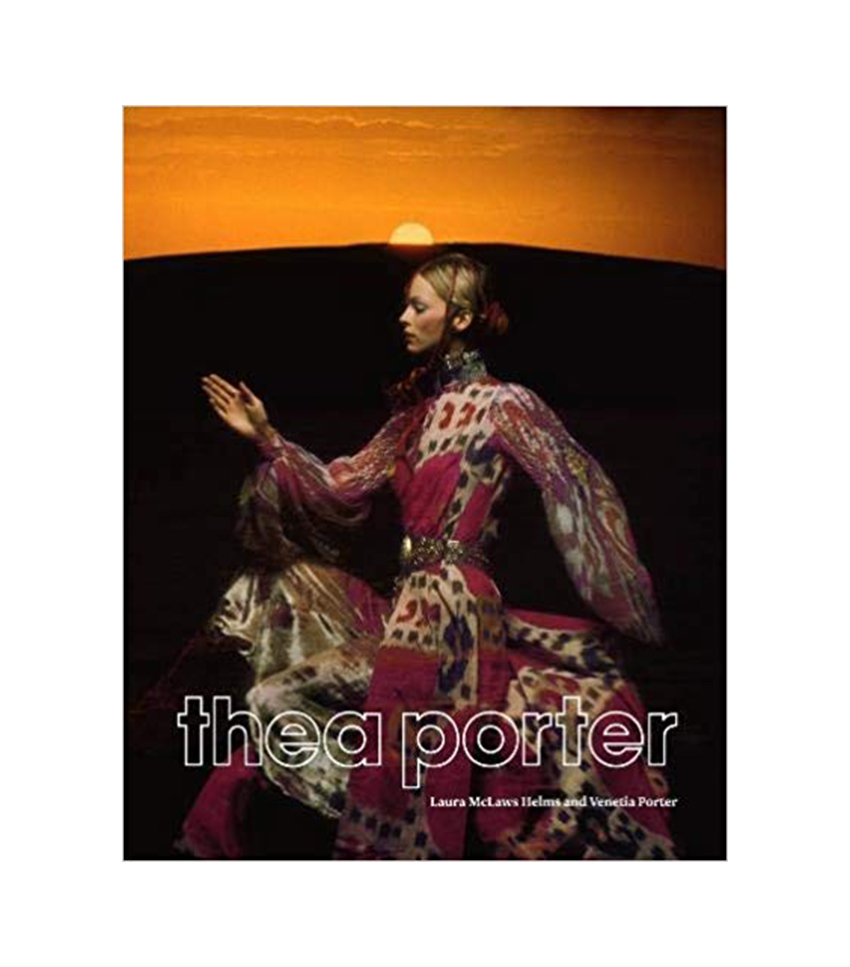

By no means am I looking to diminish the message of any movement, especially when we’re advocating for human rights and bodily autonomy, but fashion doesn’t have to take away from the message or the fight; it can add to it. How you choose to dress can speak to your beliefs and your gender identity. The slogan t-shirt you choose to wear says way more than what’s just on the surface—every purchase you make impacts the environment and the communities that are producing the products you buy. But you don’t have to take my word for it. Ahead, I’ve tapped fashion historian Laura McLaws Helms to speak to the intersection between style and politics and how style can be a form of dissent.

Tell us a little about yourself. Where did you study?

I grew up in New York City and London. I got my BFA in photography at Tisch School of the Arts, NYU, and then went on to get my masters from FIT in fashion and textile studies. Afterward, I did two years toward a Ph.D. in fashion history at LCF. Even as a little child, I was interested in fashion and especially historic fashion—poring over old photo albums, digging through trunks in my grandparents’ attic, obsessing over paper dolls based on past eras. As soon as I could read, I was learning about fashion, and then I started collecting vintage from secondhand shops and car boot sales when I was a pre-teen, so it is unsurprising that I made fashion history my career.

As a fashion historian, how would you describe your job to those who don’t know what that is?

I study, research, and write about the interconnections between fashion and culture throughout history—looking to situate dress as an integral part of the culture, both shaping and shaped by how we live our lives. Most of my work currently is writing articles and consulting with brands about fashion history, but I’ve also curated museum exhibitions, written books, and given talks/seminars about fashion and cultural history.

You have a serious vintage collection. What era of clothing do you personally love and collect the most?

I really adore 1967 to 1973. It was an era of real fantasy in fashion. Historic revivalism met Bohemian luxe in a theatrical ode to times past and far-off places.

Why do you think that in spaces of academia, and wider society, people are quick to dismiss the importance of fashion and its role in both historical movements and the cultural zeitgeist?

For centuries, society has seen fashion as frivolous and the purview of bored women with brains only for feathers and furbelows. While academic publications that have centered dress as a vital aspect of culture have begun to shift attitudes, it has been a very slow process over the last 60 years—though I’ve definitely seen an increase in acceptance and understanding of the value of fashion history and fashion itself in the last 10 years.

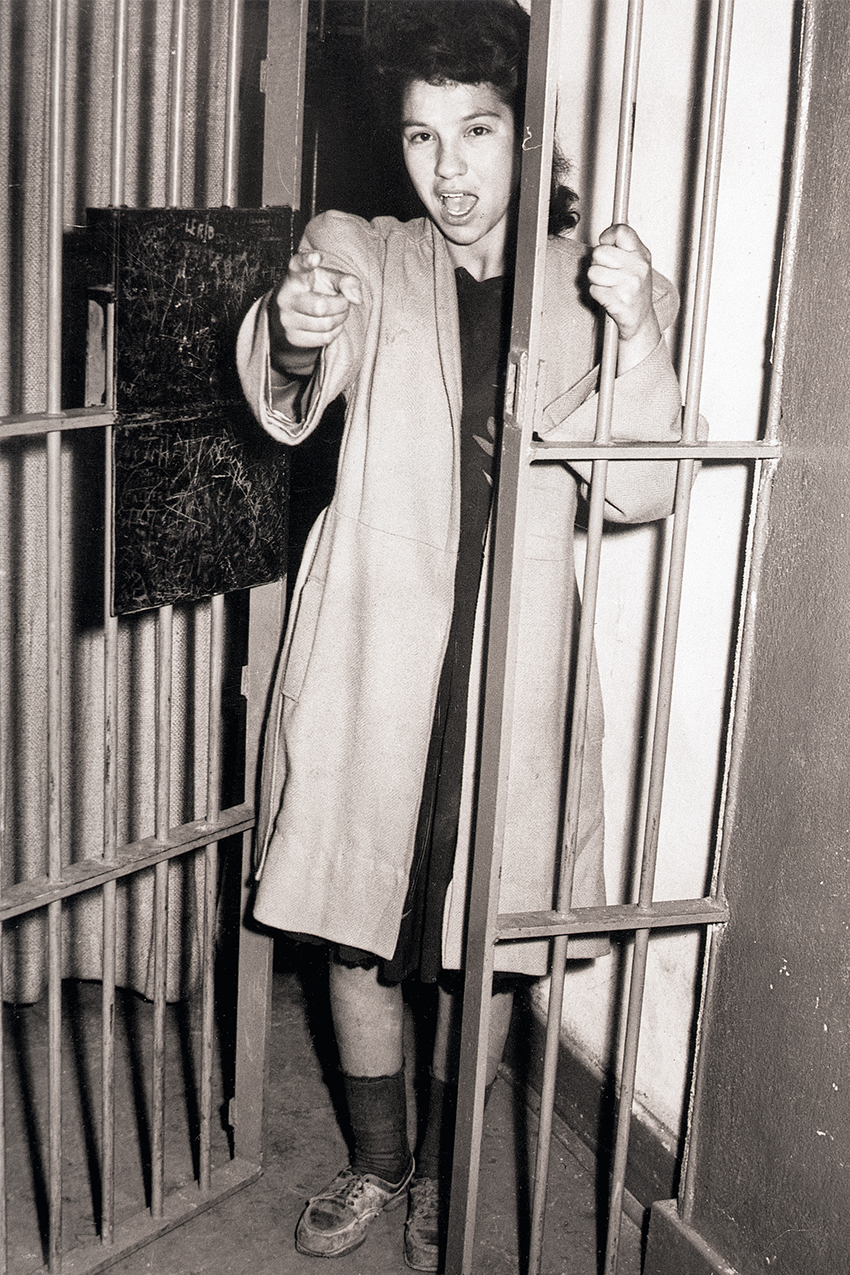

From a historical lens, what examples would you give to shed light on the fact that marginalized communities use style as a visual indicator of their dissent against the political systems and societal “norms” that oppress them?

Often as a form of dissent, marginalized groups take aspects of their oppressor’s dress and subvert it. This can be very clearly seen by feminists over the years that have adopted masculine clothes—playing with androgyny, hinting at homosexuality, covered up in a suit or pants yet skirting the edges of what was considered “proper” and “appropriate” for a woman to wear. Lesbians like Romaine Brooks and her partners Natalie Barney and Lily de Gramont wore variations of masculine dress not in an attempt to pass as men but as a signal—a way of making their sexuality manifest. While gender fluidity and sexual freedom are accepted and understood (by most) today, in earlier decades, they were viewed with panic and as morally wrong.

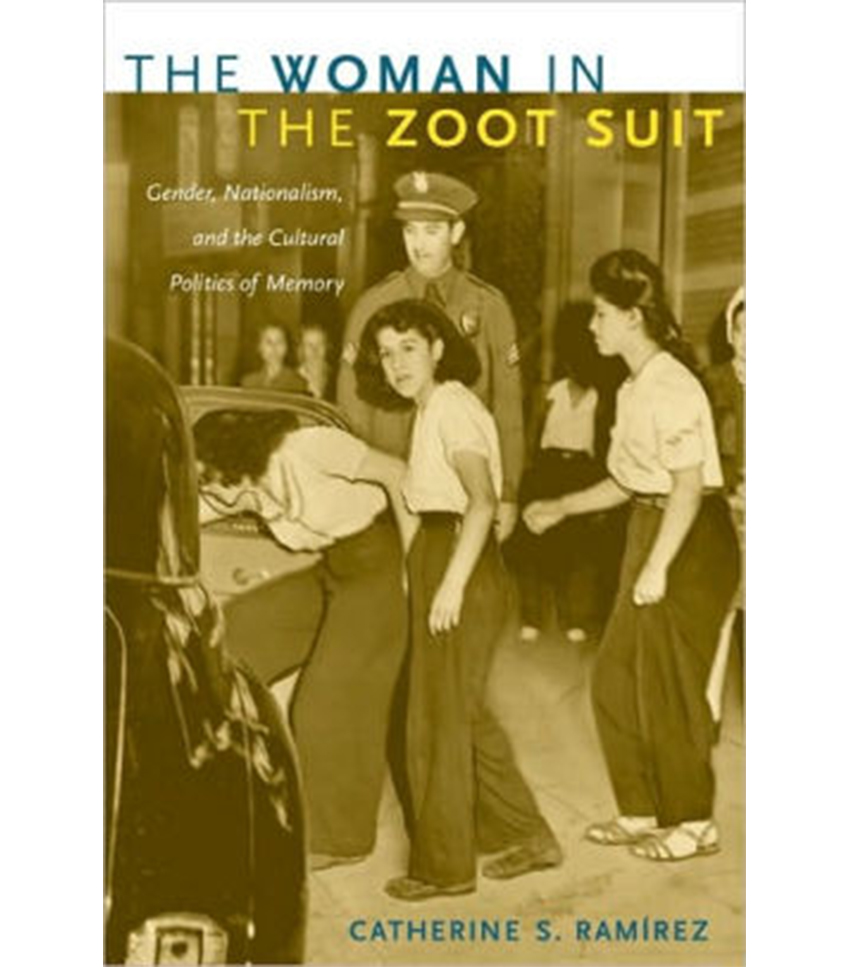

Zoot suits were another form of subversive dress and bricolage. They were developed and popularized in African American and Mexican American communities in the 1940s, and for the wearers, the extravagantly flamboyant suits were a repudiation of the constrained and boring suits (and lives) of white society as well as a declaration of freedom and self-determination. The rebellion inherent in their exaggerated proportions led them to be associated in the media with delinquency, and many considered their voluminous use of fabric as wasteful and unpatriotic in light of textile rationing during World War II. The Zoot Suit Riots occurred in Los Angeles in 1943 when American servicemen and white civilians attacked and stripped primarily Mexican American youths clad in zoot suits; rooted in racism, white Americans viewed the zoot suits as an affront on traditional American values.

Though we’re living in 2023, there are a lot of misconceptions about feminism, specifically how it impacts the clothing women who identify as such choose to wear. Why do you think society as a whole tends to think a feminist can’t dress in a “feminine” way?

Often, the media has depicted feminism as a total rejection of femininity and sexual orientation instead of a push for equality and a rejection of patriarchal dominance. While there have definitely been feminists who have rejected femininity and all its associated worlds (fashion, beauty, etc.), most have sought to remove the traditional strictures put on feminine life—the idea that women’s place was in the home, solely devoted to raising children and doing housework, all while looking fresh and beautiful for their husband. The happy homemaker, as she was so lovingly glorified at the time. Femininity and feminism do not have to be mutually exclusive, though they are often considered that way. And furthermore, identifying as a feminist doesn’t determine your sexual orientation.

How has the way a typical “feminist” dresses evolved, and why do you think it’s so hard for society to believe that a woman can be both a feminist and still love fashion?

I don’t believe that there is a typical feminist or typical feminist dress. One of the greatest shifts to happen during the tumultuous changes of the 1960s was the breaking down of the idea that there is a single acceptable way for a woman to dress. Once any style is available and acceptable (jeans, suits, flowing dresses, etc.), the need to use dress to broadcast one’s beliefs and political alignments becomes less necessary (though still a totally valid mode of expression). A feminist can wear whatever she pleases today. I think in general, society is becoming more understanding that feminism does not equate to anti-feminine.

In terms of trends, which era indicated the greatest shift in women’s role within society?

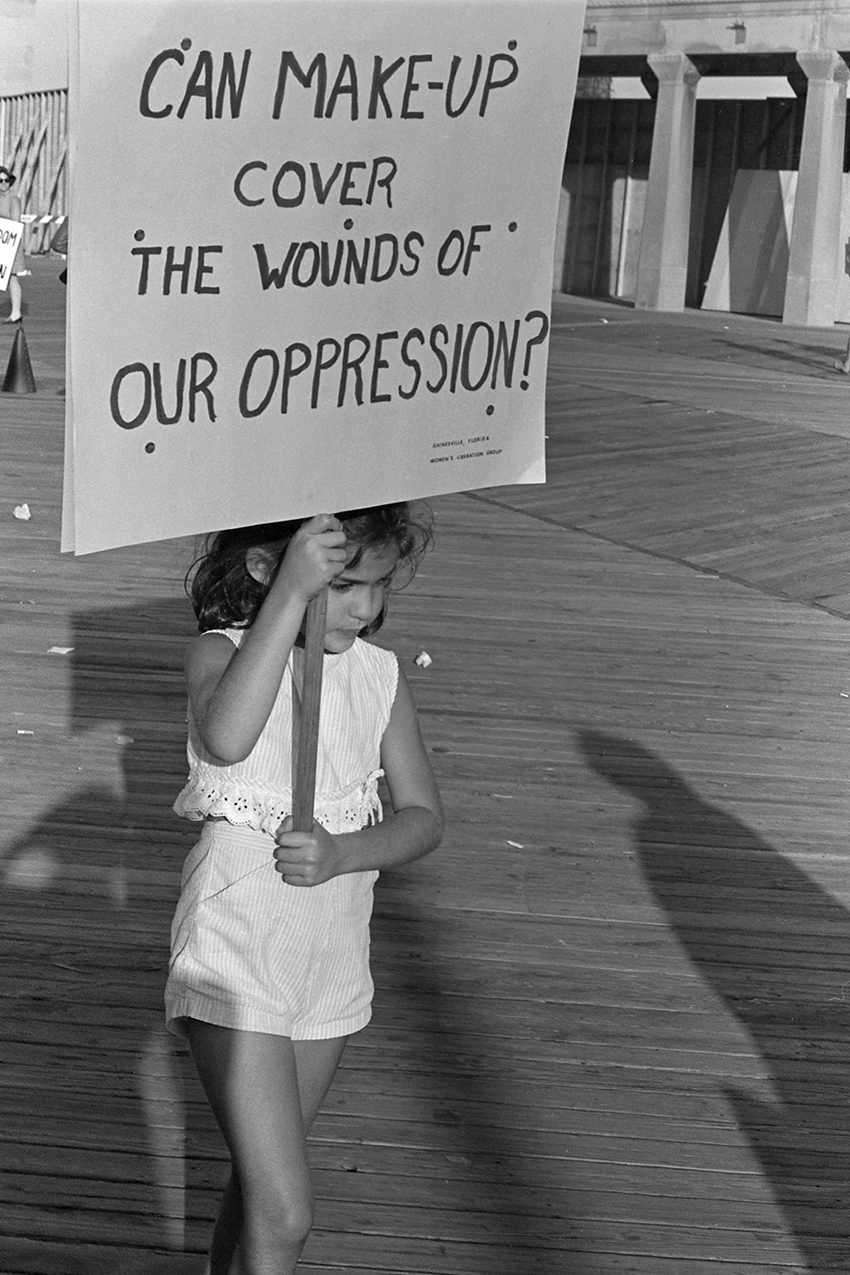

The greatest shift in a woman’s role in society probably occurred in the 1960s. While the whole 20th century was full of advances in women’s rights and shifts in status, the 1960s was a decade of dramatic changes in women’s lives and also in their dress. At the turn of the decade, women were still expected to wear gloves, stay home, be docile, not enjoy sex. The pill was approved by the FDA in 1960, dramatically changing women’s sex lives and allowing women the opportunity to postpone children while pursuing careers. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin at the same time that miniskirts began to unveil women’s legs, for the first time not on a beach. All of the advancements in the women’s liberation movement and civil rights were so deeply connected with the opening up of women’s dress. In 10 years, women went from girdles, stockings, and gloves to no bras, pantyhose (first introduced in 1959 with the first seamless ones appearing in 1965), miniskirts, and jeans for everyday wear.

How do you feel culture uses style now as a political statement?

For the last few years, we have seen many fashion designers sending down their catwalks pieces that state in bold text grand political statements. Drawing clearly on Katharine Hamnett’s iconic mid-1980s political slogan T-shirts, designers like Pyer Moss and Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior have used their platforms to make clear political messages. These kinds of political slogan tees can be worn to boldly show any political allegiance, and a quick search online shows how omnipresent they are. Many elements of style that started as a sign of resistance and as a clear political signifier—like the LGBTQ+ rainbow—have now been commercialized by big business. They still have the same meaning but by becoming such a mass symbol have lost some of their anger and power.

In conclusion, style has had a place in our closets and our cultural movements. It has been an integral part of every movement, from civil rights to LGBQT+ rights, and continues to be. There’s power in choosing to let your personal style break societal gender norms or choosing to buy sustainable, ethically made pieces. But ultimately, the biggest power is speaking up; you can wear your feminist T-shirt, but if you’re not showing up to the marches or the polls, if you’re not educating yourself on the plights of other marginalized communities, or if you’re not having difficult conversations with family members, then you’re just wearing a T-shirt. Style is only truly radical when put into action.

Next: How Ivy Style Became One of the Civil Rights Movement’s Most Powerful Weapons