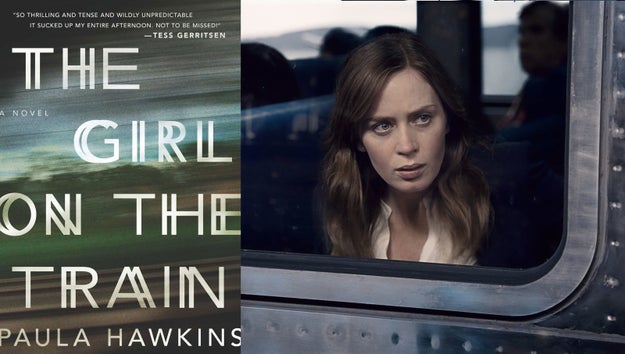

When Paula Hawkins’ novel The Girl on the Train hit stores in February 2015, it was an instant success, rocketing to the top of the New York Times Fiction Best Sellers list and staying there for 13 weeks. So it came as little surprise when, in May 2015, Universal announced it was adapting it for the screen, with The Help’s Tate Taylor directing.

The narrative backbone of Hawkins’ book remains intact throughout Erin Cressida Wilson’s screenplay. The film still revolves around Rachel (Emily Blunt) and the deeply unhealthy relationship she has with alcohol; her ex-husband, Tom (Justin Theroux); his new wife, Anna (Rebecca Ferguson); their nanny, Megan (Haley Bennett); and Megan’s question mark of a husband, Scott (Luke Evans). But the film does divert from the book in several noteworthy ways.

BuzzFeed News spoke on the phone with Erin Cressida Wilson about the scenes she cut, the characters she added, and the two sex scenes you almost saw.

1. The book was set in England, so why was the movie set in New York?

In the book, Rachel takes the train into London every day. In the film, the action has shifted to Manhattan. But Wilson says the story truly lives in Rachel’s mind.

“I always thought that the location of this film was on the train and inside her imagination, and her loneliness and her gaze out the window,” she told BuzzFeed News. “Although it was set in England, it didn’t feel to me like an overly English book. In terms of the use of cultural references, it was not extreme, so it was very simple to go from England to America in the adaptation.”

Wilson added that her primary focus in the adaptation was to translate the book’s core themes of alcoholism, voyeurism, and women’s issues, and then to — as the mystery novel had — “put them on a platter that was very popular and easy for wide audiences.”

2. Why does Rachel seem so much angrier with Megan for cheating on Scott?

As Hawkins originally wrote it, Rachel’s unwavering contempt for Anna is presented through several internal monologues, including one where she admits: “I think about sliding open the glass doors, stealthily creeping into the kitchen. Anna’s sitting at the table. I grab her from behind, I wind my hand into her long blond hair, I jerk her head backwards, I pull her to the floor and I smash her head against the cool blue tiles.”

In Wilson’s screenplay, a lot more of Rachel’s rage — including the aforementioned violent fantasy (pictured above) — is directed at Megan.

Throughout the novel and the film, Rachel’s liquor-soaked memory often conflates Anna and Megan in her head. Wilson explained that Rachel’s rage was a result of sadness and grief over her husband’s affair with Anna and the dissolution of her marriage, and Rachel starts casting that rage onto another cheater. “When she sees that Megan, in fact, seems to be having an affair, she projects her feelings about Anna onto Megan. She’s getting a little mixed up. And I think even without drinking … people can do that when you’ve been cuckolded.”

By shifting emphasis to Rachel’s anger toward Megan, the film attempts to cast more suspicion on Rachel as the murderer in the eyes of audiences.

3. What is accomplished by actually having Rachel be a member of Alcoholics Anonymous?

A particularly emotional scene features Rachel at an AA meeting, talking about how she woke up covered in blood and bruises the morning after Megan went missing. In the book, Rachel talks about — but never goes to — an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

For Wilson, incorporating AA into the movie provided an opportunity to give life to Rachel’s mind-set. “I really needed to dramatize and clarify that she was taking strides towards her own healing and her own sobriety — and that she was actually thoroughly frightened about what she may have done,” she said. “This was something that was so beautifully done in the book through inner monologue, but I couldn’t just have a whole film filled with inner monologues. So going to Alcoholics Anonymous was a very simple solution to that problem.”

Additionally, Wilson felt the film should not only deal with alcoholism, but with how one loses grip on their sobriety. “I think that what most of us know about alcoholism is that it’s a disease that creeps up on you,” she said, adding that the day someone stops drinking is often quite clear, but it’s less obvious when someone slips. “Sometimes you look at someone and it’s like, ‘I thought you quit drinking! I thought you worked the steps?’ That’s what I wanted to do with her: have her quit and then show how she starts again. Because, really, it’s not so simple. It takes more to find sobriety.”

4. When did the two cops become one?

Two officers work on solving Megan’s disappearance in the book, but in the movie, that responsibility falls to only one: Detective Riley (Allison Janney). The condensing was a no-brainer: “It’s what you do when you have Allison Janney,” Wilson half-joked. “My jaw-dropped at her performance. You think that part is sort of a regular part until she steps into the shoes of the officer. She just filled it with such dimension and by giving her the whole shebang, the whole police thread, I think it was the right choice.”

The role was given even more weight with a few additional scenes, including one where Riley and Anna talk about Rachel’s instability. “I needed to enhance the outward threat to Rachel,” Wilson said of writing more for Riley. “In the book, her inner threat is so strong; the fear of herself and her inability to remember and the false memories. In the film I wanted to increase the exterior threat. So that’s why Allison’s part was bigger and was an important part of the climax of the film.”

5. Why did the film omit Megan’s “baby killer” story line?

During a session with her psychologist, Kamal Abdic (played by Édgar Ramírez in the film), Megan eventually admits that when she was a teenager, she bore a child who later drowned in the bathtub as a baby. The revelation, as told in the book, includes Megan’s confession that she never wanted the pregnancy in the first place, leaving the reader to ponder if Megan may have passively murdered her child. The admission makes its way into a 24/7 news cycle that voraciously covers every moment of her disappearance, and Megan is soon branded “a baby-killer” by the press. The latter sequence is entirely omitted from the film.

“I wanted to keep the complexity of the female experience in the film as much as it is in the book, and the subject of not wanting a child is a very interesting subject, one that’s not dealt with very much actually,” Wilson said. “However that complexity was not serving the story of what became the film.”

6. What happened to the scene where Scott and Rachel have sex?

Rachel’s growing infatuation with Scott is well-represented on screen (his peek-a-boo underwear moment!), but — unlike in the novel — Rachel and Scott never sleep together in the movie. “I really wanted Rachel to be purely fixated on fantasy and on her ex-husband,” Wilson said. “I didn’t want her to be embarking on romance, touching people; I wanted her purely in the realm of fantasy and frustration and dreaming and sadness.”

Although she did originally script two love scenes, they both ended up on the cutting-room floor for the same reason. “I felt like that scene — which I wrote and had in the first draft as well as another scene where she has sex with someone else, a married guy on the train — really destroyed my belief in Rachel,” she said. “Just because she’s an unreliable character doesn’t mean she has sex with anybody who walks by her. It was important to keep her a little virginal.”

7. Where did Lisa Kudrow’s character come from?

Of all the notable characters in the movie, only one is a total Wilson invention. Martha (Lisa Kudrow), the wife of Tom’s former boss, isn’t in the film much, but her appearances are crucial: The sight of her in passing causes Rachel to flashback to a party where she’d apparently made a drunken spectacle in front of Martha and Tom’s work colleagues. And an actual encounter with Martha allows Rachel to reexamine truths behind her alcoholism, her marriage, and how both are linked to Megan’s disappearance.

“The gaslight of the film became something that really needed to be dramatized more than the book did, because it wasn’t going to read as strongly on screen,” Wilson said of Rachel’s slow realization that Tom was manipulating her. “I think that you needed to be hit harder with that information, and Tate had this idea to just have Lisa Kudrow literally say it. No more beating around the bush. I think there are moments where it’s right to do that, and that was the moment. To take an element of the book that was already there and turn it into a living, breathing character in Lisa.”

That second scenario also offers an unexpected twist for fans of the book: Rachel’s shocking golf club attack from the book is actually committed by Tom in the movie. “It’s one of those things where the book has all these stars that burn really bright that you hang onto and they’re all saying, ‘This is The Girl on the Train experience.’ All those stars or hooks needed to be in the film, but sometimes they needed to be a bit different. It’s important when adapting such a popular book to hit all those points but also break out expectations without slaughtering the book. And that was, for me, the joy of adapting the book.”